In this progressive blog post, Dr. David Reid, the Remote Laboratories Experimental Officer at the School of Engineering, University of Edinburgh, explores the transformative potential of using learning analytics for effective formative feedback in educational settings. Highlighting the shift from traditional feedback methods to innovative, student-centred approaches, Dr. Reid elaborates on how remote laboratories and smart learning analytics can revolutionise the way feedback is integrated into the learning process. This approach not only enhances student engagement and understanding but also aligns perfectly with the modern educational need for flexibility and self-directed learning. This post belongs to the Jan-March Learning & Teaching Enhancement theme: Engaging and Empowering Learning Engaging and Empowering Learning with Technology.

The need for learners to receive feedback during learning activities is no longer questioned. However, for practical reasons, such as high student to staff ratios and constraints on learning spaces and timetabling, feedback received by students in UK higher education tends to be summative (assessment of learning) rather than formative (assessment for learning). That is, feedback is typically delivered after learning tasks are concluded and students are given little opportunity to actively reflect on and update their learning as a result of feedback. Student dissatisfaction with the current provision of feedback in higher education is reflected in the relatively low National Student Survey satisfaction ratings for assessment and feedback, particularly when asked “How often does feedback help you to improve your work?”

Human engineered feedback loops – the use of a system’s output to modify input in order to reach a desired goal – have historically featured in automated mechanisms to control outputs (e.g. float regulators in ancient Greek water clocks or temperature control in heating systems). However, the ubiquitous presence of digital sensors in our modern world now enables feedback loops that support people to make informed decisions and self-regulate their behaviour without enforcing strict control over the output. Examples include dynamic speed signs that slow drivers down without punitive action and smart meters that help conserve energy in our homes.

The evolving use of feedback loops in society mirrors the evolution in pedagogical techniques used in UK schools and universities. Traditional, didactic methods are making way for more active, constructive and self-regulated approaches. As teaching and learning methods transition from teacher-dominated towards increasingly student-centred, we also need to shift feedback mechanisms from something that teachers do, towards activities that engage students in their own self-regulated learning. That is, the mechanistic view of feedback, whereby the “expert” provides feedback to “correct” student behaviour, must make way for (appropriately presented) on-demand, multi-dimensional information that students use to inform their self-regulated decisions during learning.

This is the approach that the Remote Laboratories team in the School of Engineering are taking to support the delivery of engineering practical work. Remote laboratories remove many of the physical and temporal constraints of traditional lab work by providing students with 24/7 access to real hardware, in real time, through a web browser. We have previously shown that students perceive little difference between remote and in person lab modes regarding each mode’s potential to support traditional engineering lab objectives. However, students report that flexibility of access is a significant advantage of remote labs and open access to remote hardware naturally supports extended tasks where students can re-engage with activities after feedback is received.

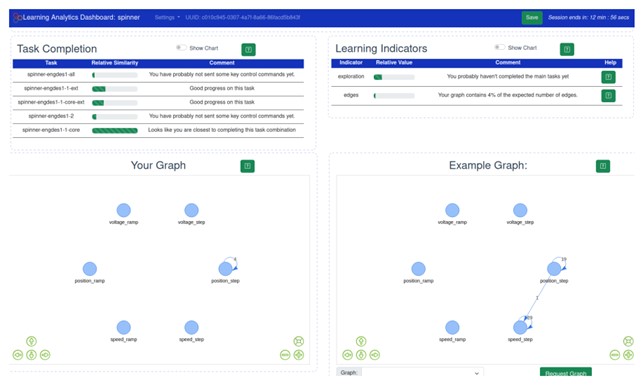

Further, remote laboratories are a digital learning tool that supports the logging and analysis of student interactions (e.g. clicks and inputs on the user interface) upon which automated feedback can be generated. We have developed a learning analytics system that analyses these interactions using a novel graph-based technique that goes beyond the common use of “click counts” as a measure of engagement. Our analysis generates graphs (i.e. networks) of student activity that can be compared to expected activity derived from the procedure the teacher follows to complete lab tasks. This could be extended to other reference frames such as other students on the course, a previous cohort’s activity or that of known problematic procedures. It could also be extended to other digital learning tools (e.g. Jupyter notebooks, online courses, Learn, online discussion boards etc.) where an accessible data stream is available. Our learning analytics system also provides automated estimates of various learning indicators, including task completion and engagement, using a novel graph dissimilarity algorithm (TaskCompare). This is a deterministic technique that does not require training datasets, so is available after the first interaction of the first student on a new course. These visualisations and analyses are provided, on-demand, to students via a student-facing learning analytics (SFLA) dashboard during remote lab activities (see Figure 1 for an example).

As with home smart meters and dynamic speed displays, our SFLA learning dashboard is not proscriptive. Instead, it provides students with information upon which to self-regulate their own learning in the moment. The dashboard places the responsibility for engaging with feedback on students and gives them control over the information on display, whilst also surfacing relevant data upon which traditional feedback techniques could be based (e.g. teacher-student dialogue in class). Our dashboard also presents current activity and expected activity in the same format (as graph visualisations). This has the potential to help students clarify what good performance is, as written material can often lead to a mismatch in student and teacher perceptions of goals. Perhaps most importantly though, the existence of the dashboard encourages students to take the time to stop and reflect during learning.

The positive impact of our SFLA dashboard was demonstrated during workshop sessions with a large (450 students) first year engineering course in 2022-23, where students who engaged with the dashboard were twice as likely to complete tasks as expected than those who did not.

To conclude, teacher-dominated models of feedback are difficult to embed at the scale and frequency necessary in typical university courses and subsequently hinder the adoption of research-supported approaches to learning, such as active learning. Designing novel approaches to generating automated formative feedback, including the SFLA dashboard discussed above, not only reduces the burden on teaching staff, but empowers students to take responsibility for their own learning and can support more active, constructive and engaging learning activities.

David Reid

David Reid

Dr David Reid is the Remote Laboratories Experimental Officer in the School of Engineering, University of Edinburgh. His research focuses on the use of learning analytics to understand and support active learning in STEM education, including how educational models can be used to inform the design and evaluation of remote lab experiences and other digital tools. He was formerly Lead Physics teacher at the British School in Tokyo.