In this insightful post, Sarah Ward, a Lecturer in Learning in Communities at Moray House School for Education and Sport, explores the potent role of Small Group Learning (SGL) in enhancing student engagement, particularly within the MA Learning in Communities programme. Addressing the unique challenges faced by ‘widening participation’ students, who often balance intense personal and professional demands alongside their educational pursuits, Sarah illustrates how SGL not only deepens motivation and supports cognition but also fosters essential relationships among students. This post belongs to the Jan-March Learning & Teaching Enhancement theme: In-class Perspectives to Engaging and Empowering Learners

Wouldn’t we all love to be a teacher whose classes are ‘unmissable’ (Revell and Wainwright, 2009)? It’s perhaps no surprise that students highlight participation, alongside clarity and enthusiasm, as key to engaging and empowering learning. I’ve found that Small Group Learning (SGL) is a useful tool to structure student participation over the duration of a course. SGL supports student participation in three valuable ways: by deepening motivation, building relationships and supporting cognition (Springer et al., 1999).

Motivation, relationships and cognition are central for all student learning but are critically important for ‘widening participation’ students at Edinburgh. As part of the University’s Widening Participation Strategy 2030, Moray House offers the MA Learning in Communities, a professional undergraduate qualification in Community Learning and Development (CLD), which spans SCQF levels 7-10. Students tend to be non-traditional learners, often returning after a period out of education but bringing a wealth of life and practice experience relevant to the CLD curriculum. Coming into the university can be a daunting experience. Many of our students are the first in their families to go to university, and are juggling the demands of jobs and busy family lives alongside their studies. Achieving the standards at degree level requires intensive academic skills development. Deepening motivation, building relationships and supporting cognition through SGL are all crucial scaffolds to student success.

I consider the optimal SGL group size as similar to a research focus group, with around six participants encouraging contribution by all while offering some diversity of experience. Small groups can accommodate varied participation techniques, from appreciative enquiry to ‘open space’ and ‘carousel’ methods (New Economics Foundation, 1998).

Motivation

SGL encourages students to bring their lived experience as community activists and educators into the classroom. Students who are not comfortable speaking to a whole class are more likely to engage and offer opinions in a small group of peers. At the beginning of the course, I invite student pairs to critically discuss a class reading or reflect on practice experience, joining up with other pairs as they increase in confidence and skill. Students feel accountable to their peers, so creating the expectation that all students will be expected to contribute in every class encourages good habits of academic preparation. Regular, informal presentations of SGL work builds confidence and clarity. In the latter stages of a course, formative and summative group presentations allow students to gain recognition for collaboration and creativity.

Relationships

Co-creating knowledge in small groups aligns well with the theories of dialogue that we study on the MA LiC programme (Westoby and Dowling, 2013). ‘Turning towards the other’, dialogue as a ‘third’ space, and creating collective coherence are all relational concepts that we explore on our second year course, Community Learning 2: Working with groups. Modelling dialogue techniques in small groups gives students the chance to build the relational skills that are central to CLD practice. Strong and sustained peer relationships also support emotional wellbeing. In recent feedback, one student said, ‘when one person is feeling down, a group can prop you up.’ Building trust creates a positive and open learning environment, where students can test their learning without fear of failure. There are times when cohorts experience differences and divisions too. Maintaining structured dialogue within the curriculum helps students to find ways to honour dignity and respect alongside difference.

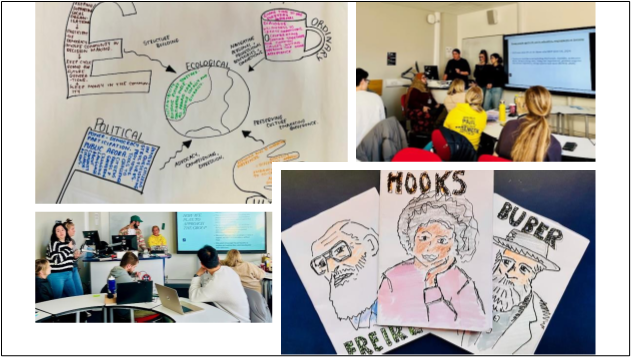

I aim to balance self-selected groups with opportunities to mix with other students. Sustained interaction in a new group can give students fresh perspectives. This semester, we explored a challenging topic on community conflict using a carousel approach, where groups moved around four ‘stations’ on the topic of conflict (Maoist, Alinskian, Christian and Gandhian) to explore and build their understandings. This promoted deep dialogue on student responses to violent and non-violent resistance in communities.

Cognition

Course feedback tells me that SGL helps students to ‘build on each other’s strengths’ and deepen understanding. One student explained that ‘peer explanation can be more enlightening than your lecturer when you’re confused.’ SGL promotes deep thinking and consolidates learning. In a workshop environment, groups can regularly co-produce learning materials to present to others, such as a posters or zines. These methods support diverse learning needs: while some students enjoy learning through small-group dialogue, others like to use creative and visual skills to capture learning on paper. Circles and linear maps take dialogue down interesting routes while creative arts materials allow for emotional expression and reflection. I bring a bag of flipcharts, pens and craft materials to classes and student produce fun and useful learning aids, which we upload as images to Learn every week. Zines are a quick way to summarise learning and can be created collaboratively. Our students have created zines on key theorists from the core text, which remind them of key concepts and application, and offer a quick reference point.

SGL takes some additional preparation but offers a fun and exploratory format for classes. While ‘unmissable’ might be an unrealistic goal, student participation creates a fun and dynamic learning environment that takes co-produced learning in interesting directions – not only for the students, but for teachers too.

Source: Author

Sarah Ward

Sarah Ward

Sarah Ward is a Lecturer in Learning in Communities at Moray House School for Education and Sport and is Programme Director for the MA Learning in Communities programme. Her research explores how community learning and development supports voice, participation and activism.

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/sarah-ward-16825a87

Twitter: @sward2205