In this post, Dr Jenny Scoles describes a SHED event she recently attended at Edinburgh Napier University, which explored how we could embed sustainability in the curriculum. This post is co-authored with the speaker at the event, Professor Mark Huxham, and summarises the key points of his presentation on how we should approach embedding sustainability in the curriculum; a topic close to his heart for the last 30 years. This post is part of November and December’s Hot Topic Theme: COP26 and embedding the climate emergency in our teaching.

The need for a commitment to embed sustainable development in all Higher Education teaching should be obvious in the week following COP26. Our students must not only be equipped intellectually to help drive the rapid change we need, they also must have the emotional and spiritual resilience to deal with the sustainability crises that will impact their lives. Furthermore, recent polling shows that students are demanding more teaching on sustainability.

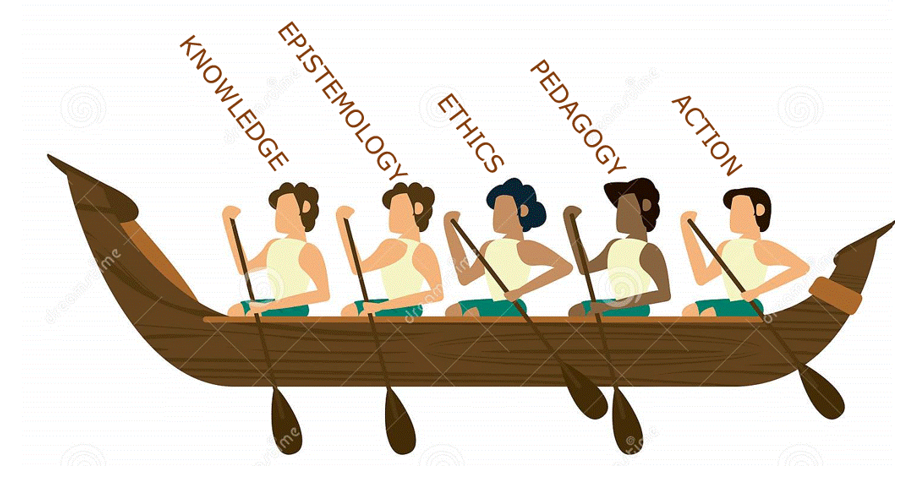

Adopting the metaphor of a boat in which we are all travelling, Mark suggests that five ‘paddles’ will be needed to help navigate the choppy waters ahead: Knowledge, epistemology, ethics, pedagogy, action. A curriculum supporting sustainability needs to have all of these onboard.

1. Knowledge

Mark argues that all students, regardless of discipline, will need elementary understanding of two key crises:

- Biodiversity crises: We are in the midst of the 6th mass extinction event on Earth, and are likely to lose between 25-50% of all species in the coming century. Students need to understand the links this has to human welfare.

- Climate change crisis: While no one person can understand anthropogenic climate change, since it is such a huge and multi-disciplinary problem, everyone should have a clear understanding of the main trends, drivers and risks. For example, all students should understand the notion of a tipping point, and why that may make apparently small, average temperature increases so dangerous. Such non-linear change is a cross disciplinary idea, with examples such as revolutions from history and inflationary spirals in economics.

2. Epistemology

Over the past decade, we have had sobering and deadly reminders of how powerful interests work to spread doubt and undermine certainty about securely founded and vital knowledge. Climate change denial, often funded by fossil fuel interests, is one of the most egregious examples. A critical role as scholars is to equip students with the ability to discern the difference between more and less reliable knowledge. With this comes the argument that we need to move away from relativism and defend objectivity – an unpopular stance for some! In short, we need to be teaching students the philosophical foundations of knowledge, and where knowledge comes from.

3. Ethics

We need to consider ethics in all our teaching. For example, we are quite bad these days at thinking in multi-generational terms, and yet intergenerational ethics is essential in sustainability. This can be termed ‘cathedral thinking’. Historically, we were not always this remiss. For example, the foundation stone for the world’s tallest church, Ulm Minster, was laid in 1377 yet the church was not completed until 1890. Those who laid the foundational stones were doing so knowing they would not be alive to see the completion of their efforts. We need to challenge short-term thinking. For example, in economics, discounting is routinely used to devalue the future.

4. Pedagogy

The way we teach our students is key to embedding a hopeful approach to tackling climate change in the future. Students need to work in democratic, interdisciplinary teams in order to tackle the multifaceted nature of wicked problems, such as climate change. Yet this presents a real challenge as we struggle to shift from a systems and structural point of view that keeps disciplines and professions in silos.

5. Action

A recent European survey revealed that 56% of young people think the human race is ‘doomed’. That is, over half of the younger generation are feeling hopeless and fatalistic. As academics, we cannot stand in front of future generations – our students – and deliver this devastating news with no glimmer of light. We need to give students grounds for hope, and the way to do this is to offer possibilities of taking action. For academics, this is a radical departure from some as it is upending a long-felt belief that we need to stay neutral in science, and asks us to step over into a political realm. Our students need to help us do this and be part of this change.

SHED (Scottish Higher Education Developers) is a wonderfully supportive and collegiate group comprising academic developers and others with an interest in supporting learning and teaching in HE. SHED events are held throughout the year, both online and in-person, with the aim of supporting practice, and offering opportunities to engage in CPD. If you are interested in learning more about SHED, please get in touch with Convener, Hazel Christie: Hazel.Christie@ed.ac.uk.

Jenny Scoles

Jenny Scoles

Dr Jenny Scoles is the editor of Teaching Matters. She is an Academic Developer (Learning and Teaching Enhancement), and a Senior Fellow HEA, in the Institute for Academic Development, and provides pedagogical support for University course and programme design. Her interests include student engagement, professional learning and sociomaterial methodologies.

Mark Huxham

Mark Huxham

Mark Huxham is Professor of Teaching and Research in Environmental Biology at Edinburgh Napier University. He works on the ecology of coastal ecosystems, with particular expertise in mangroves, having spent many years striving to conserve and restore these remarkable forests. After researching how mangroves trap and store carbon, he helped establish Mikoko Pamoja, the world’s first community-based mangrove conservation project to be funded by the sale of carbon credits. Mark also researches teaching and learning in higher education, looking at new models of partnership between teachers and students and how to use feedback and assessment to encourage deep learning.