In this third post for the Mini-series on the “Curriculum as a Site for Social Justice and Anti-Discrimination”, Ibtihal Ramadan draws from her extensive research among Muslim academics in British universities to question whether Equalities, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) policies suffice in honestly challenging Islamophobia at universities…

Within Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), the institutional discourse and policies about EDI appear to be flawless, yet the reality of staff and students from Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) backgrounds shows that universities are lagging behind in walking the walk of EDI (Ahmed, 2012, Ramadan, 2017). While racism or Islamophobia at universities is not atypical to the experiences of BME individuals, discussions about racism within teaching and learning remains curiously silent (even with the recent focus on the murder of Mr George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement). What then of Islamophobia? In this short blog, I would like to discuss how Islamophobia impacts on the day-to-day experience of Muslims within university learning and teaching spaces. I will reflect on what we can do as staff to challenge Islamophobia within HEIs. I draw from my own experiences as a student and, now, as a tutor and lecturer.

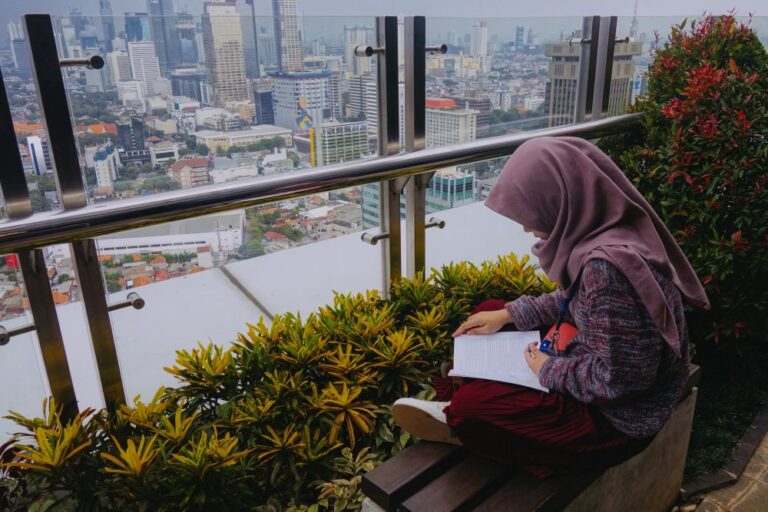

As a Muslim woman who practices the hijab, I have personally experienced gendered-Islamophobia since I have arrived as an international student to commence my postgraduate studies at the University of Edinburgh. I was constantly at the receiving end of patronising comments and banter from staff and students about being a product, albeit exceptional, of an oppressive culture, manifested through my dress style, which, my tutors and peers thought, did not sit well with my own progressive thinking and articulate nature.

In some occasions, I had to justify to fellow students why I would not socialise with them in a pub, or even why I chose not to have physical relationships with male students. While at times I felt enthusiastic about educating others, at other times explaining things to others seemed like a burden, an emotionally draining exchange, particularly when you encounter nonsensical questions. For instance, during a workshop, a white fellow student asked half-jokingly if I really have hair. I stared at her and remained silent, while my Japanese friend, who visits me often, frustrated by this uncivil question, started to explain that I do have hair. I politely asked my friend to ignore the white student’s question as it is unworthy of answering. All of these experiences are common to Muslim women at universities for whom Islam is an integral part of their outlook on life. Such experiences have created, amongst hijabed women students, feelings of insecurity, alienation, being out of place, and even drove some of them to take off their hijab to reduce discrimination and try to fit in.

Furthermore, the Prevent duty serves as a reminder that regardless of espoused EDI policies, there remains the reality of structural Islamophobia. For instance, Prevent policy aims at tackling all forms of ‘ terrorist ideology’; yet in reality, the implementation of the policy is focussed on ‘de-radicalisation’ and disproportionately targets individuals of Muslim backgrounds, including Muslim students at schools and colleges (Busher et al., 2017). University sites are not excluded, see Qurashi (2017) and Guest et al (2020) on how Muslim university students, especially those with visible faith identity, are more prone to being suspected and experience greater scrutiny due to the institutionalisation of Prevent at HEIs. Prevent has unjustly suspected Muslims, subjected them to constant surveillance, but also stifled discussions around sensitive topics in classroom settings and beyond. In my experience, there appears to be a silence at universities about this. Despite push back against the Prevent duty by academics (see McGovern), National Union of Students, UCU members and students unions at universities (see City Student Union), the top-down approach of the Prevent agenda made it nearly impossible to ensure that Muslims are fairly and equally treated at universities. With this backdrop, are we, as activist anti-racist educators, banging our heads against the wall? Can there be slight hope of challenging Islamophobia at universities when there is no formal government recognition that Islamophobia is indeed a form of racism? My impression is that, yes there is. But how?

Steps to Challenge Islamophobia at Universities

While what I propose here is not set in stone, it might improve the situation of Muslim academics and students in UK universities but also assist in learning and teaching environments.

First, more representation of Muslim staff is needed at various fronts in universities. This will help in supporting Muslim students to find staff members they can relate to, come to for advice, and perceive as role models. Recruiting more Muslim staff, academics or otherwise, will provide opportunities to non-Muslim students and staff to interact with Muslim staff. This will increase the opportunities to challenge common stereotypes by fostering intercultural understanding, which might temper the hyper-visibility of the political discourse on the ‘War on Terror’ that is being negatively attributed to Muslims. My PhD research, which is currently being written up as a book, examined the experiences of Muslim academics at British universities. The study found that Muslim academics within universities are continuously invested in correcting negative perceptions about Islam, and are hyper conscious of how they should present themselves, which includes self-censorship as well as identity-negotiation, to reduce the common anti-Muslim suspicion. For instance, a female participant mentioned that although her research focuses mainly on Muslim minorities within her field, she prefers to frame her research through the analytical lens of racism, on grounds of colour and ethnicity, rather than Islamophobia so as to safeguard against being seen by her colleagues and seniors as having an ‘Islamist agenda’.

Another way of combating Islamophobia, in alignment with the Decolonise the Curriculum Movement (DCM), is to diversify the course material by including obligatory readings that provoke students to think differently about Islamophobia, i.e. in a way that challenges the ‘master narrative’ about Muslims being a ‘global threat’. Such readings include the writings of postcolonial and decolonial authors, auto-biographies of and works authored by Muslims, to facilitate critical discussions in classroom context, that will increase awareness of Muslim experiences and perspectives.

Finally, while most UK universities celebrate Black History Month in which several events including talks, shows, exhibitions, lectures are held to confront anti-Black racism, few universities have opened their doors to Islamophobia Awareness Month. Allowing such campaigns will undoubtedly help challenge the extremely negative views about Muslims.

Despite this gloomy anti-Muslim picture, I should note that my own experience in contributing to teaching and giving guest lectures during my doctoral studies has been positive. I have been well-received and perceived by students and senior colleagues. I’ve received positive feedback from students during my tutoring and supervision of Masters level students. Yet, I am well aware that other Muslim academics have had less positive experiences and that they experienced and continue to experience subtle and not so subtle forms of religious or colour-based racism.

In a nutshell, universities should be the key sites of positive change to ensure equality and inclusion on societal and global levels, and they will not be able to achieve this until they moved on from the symbolic commitments revealed by policy documents to walk the real walk of EDI.

Ibtihal Ramadan

Ibtihal Ramadan

Ibtihal’s current research examines the experiences of Muslim academics working in AHSS disciplines at UK universities on producing knowledge that attempts to critically challenge the discourse that continues to problematise the Muslim presence in the West and beyond, in alignment with Decolonising the Curriculum Movement. Her theoretical lenses include Critical Race Theory, postcolonial and decolonial thought, racism and Islamophobia.