In this captivating blog post, Dr. Yoko Matsumoto-Sturt, a Lecturer in Japanese Studies at The University of Edinburgh, introduces an innovative approach to humanities education through her course, “Supernatural Japan: Doing Japanology through Yokai.” Dr. Matsumoto-Sturt explores the transformative potential of experiential learning to deepen students’ understanding of complex cultural concepts by actively engaging them in practical, hands-on activities. By discussing her journey of integrating experiential methods like handling cultural artifacts and reenacting ancient literary scenes, she illuminates how these dynamic techniques encourage deeper engagement and comprehension among students, transcending traditional lecture-based learning. This post belongs to the Jan-March Learning & Teaching Enhancement theme: In-class Perspectives to Engaging and Empowering Learners

Introduction

When I developed Supernatural Japan: Doing Japanology through Yokai, I wanted to explore how “learning by doing” (Experiential Learning) could transform humanities education. Could hands-on activities enhance understanding in ways traditional lectures couldn’t?

Typically, humanities courses rely on lectures and readings to convey complex ideas, assuming that abstract concepts or cultural nuances are best grasped through passive learning. I wondered if a more experiential approach —common in fields like science and engineering — could bring Japanese cultural studies to life, allowing students to engage more actively with the material. By interacting directly with cultural objects and collaborative projects, students could gain a deeper appreciation of the subject.

Course structure and activities

Before creating the main activities for “learning by doing,” I focused on making the classroom inclusive. I translated passages from Japanese literature and historical records into English so that students with or without Japanese language skills could participate equally.

That said, I initially didn’t expect much interest from other disciplines or schools, as yokai (Japanese supernatural beings) are still a niche topic in English-speaking contexts. But, upon launching the course, I was surprised to see an overwhelming number of enrolment requests from students outside of Japanese Studies — so many, in fact, that I had to implement a cap on non-Japanese Studies students. For a generation familiar with yokai through popular media, it seems yokai have become something of a buzzword.

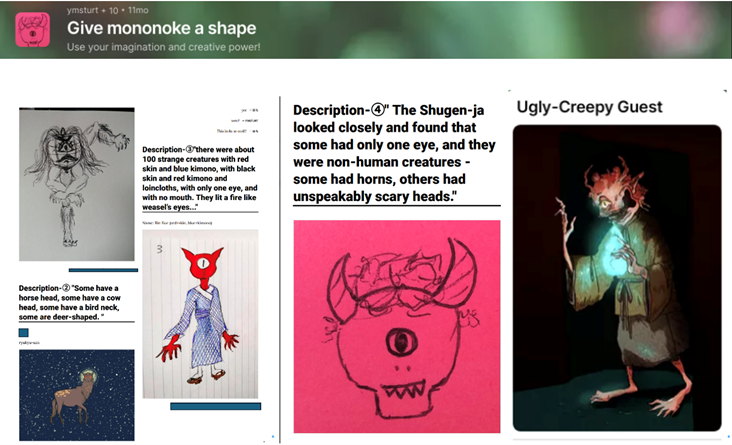

Throughout my course design, I chose not to take a ‘pop’ or ‘edutainment’ approach. Instead, I began by examining how, a thousand years ago, Japanese society regarded invisible supernatural beings, or mononoke, as a matter of life and death. The first hands-on activity involves embodying the Hyakki Yagyō (Night Parade of One Hundred Demons) from 13th-century literature, giving students a chance to experience the ancient Japanese worldview on mononoke. Students have access to the original text, a modern Japanese translation, and an English translation, providing three layers of linguistic input. They consider the types of mononoke imagined in medieval Japan and are then invited to draw one that comes to mind:

Around the middle of the course, students participate in a hands-on session titled “Reading Picture Scrolls – Just like the old Japanese did.” This class employs a flipped learning approach, meaning students are expected to be familiar with handling picture scrolls before the session. During this hands-on activity, students carefully unroll replicas of picture scrolls from the late Heian period in the Main Library’s rare book section. The session begins with questions such as, “Do you know why we unroll picture scrolls from right to left?” Students then identify elements discussed in the assigned reading for the session and appreciate the pre-modern style of vertical, brush-written text.

One of my favourite topics is the portrayal of angry and jealous oni-women. Students explore the Noh masks and stylized costumes of Lady Rokujō in the play Aoi no Ue (Lady Aoi). They watch her battle scene, identifying her as a female oni (demon) through her costume, props, and the Hannya mask featuring an open mouth, strong jaw, sharp teeth, golden eyes, and two horns. This mask’s expression is both demonic and sorrowful, capturing anger, fear, and torment.

Source: https://colbase.nich.go.jp/

Source: Author

A post-seminar hands-on session introduces students to the Japanese concept of 間 (ma, the space between), which conveys a nuanced sense of space, timing, and rhythm that goes beyond a simple definition. Since the kotsuzumi (small hand drum) is integral to Noh theatre’s musical ensemble, students explore ma through kake-goe (drum calls) and air-kotsuzumi practice with a kotsuzumi master on YouTube. Through watching this video, students gain a hands-on experience of rhythmic “ma” by practicing air drumming on the kotsuzumi. They also learn about the rituals essential to traditional arts practice from the video and engage in Japanese greetings during class.

In this way, I designed the course with a total of 11 yokai-related topics, each with a hands-on activity that connects directly to “doing Japanology.” These activities are intended to serve as entry points for understanding Japanese concepts and worldviews that are difficult to explain in words.

Impact on students

The impact of this approach is best captured through the words of my students. One student, in a testimonial submitted for the 2024 EUSA Teaching Award, wrote:

I have never had such an incredible learning experience. Although the unique content of this course can be challenging due to its nuance and philosophy, the course structure and collaborative strategies make grasping these concepts much easier. The seminars are informative yet hands-on; the physicality of some exercises makes the concepts unforgettable. This course is truly immersive. As a non-Japanese language student, exposure to Japanese materials has been invaluable and has redefined my worldview.

This feedback demonstrates how experiential learning can deepen understanding and inspire fresh perspectives, even for students from different fields. For some, the course has sparked interests in areas like translation or Japanese cultural studies, highlighting the impact of a hands-on, experiential approach. By fostering active participation and curiosity, the course empowers students to take ownership of their learning journey and explore new paths.

Conclusion

Reflecting on this experience, I see “learning by doing” as a powerful tool in humanities education. By breaking the boundaries of traditional lecture-based methods, it has made abstract ideas accessible and sparked genuine curiosity in students. I hope this post inspires other educators to consider how experiential learning might enhance their own courses, engaging and empowering students in meaningful new ways.

Yoko Matsumoto-Sturt

Yoko Matsumoto-Sturt

Dr Yoko Matsumoto-Sturt holds a PhD in Linguistics and Applied Linguistics and is a lecturer in Japanese Studies at the University of Edinburgh. She is currently working on a kanji experiential learning project and conducting research on visual media discourse. Her course, Supernatural Japan: Doing Japanology through Yokai, has received multiple nominations for the EUSA Teaching Award in the Outstanding Course category. (Click the link for my recent journal article on female demons.)

((Reading Picture Scrolls class))