In this post, Dr Ross Galloway, a Senior Lecturer in the School of Physics and Astronomy, reflects on the unexpected outcomes when trialling an assessment rubric to promote expert-like behaviour in an introductory physics course…

The phrase ‘jumping through hoops’ is almost never used in a positive sense, and brings to mind arbitrary, pointless or bureaucratic activity. If we’re honest, a fair bit of hoop jumping can go on in universities; a few years ago I discovered I was inadvertently making my students do it, even though my motivations had been well-intentioned.

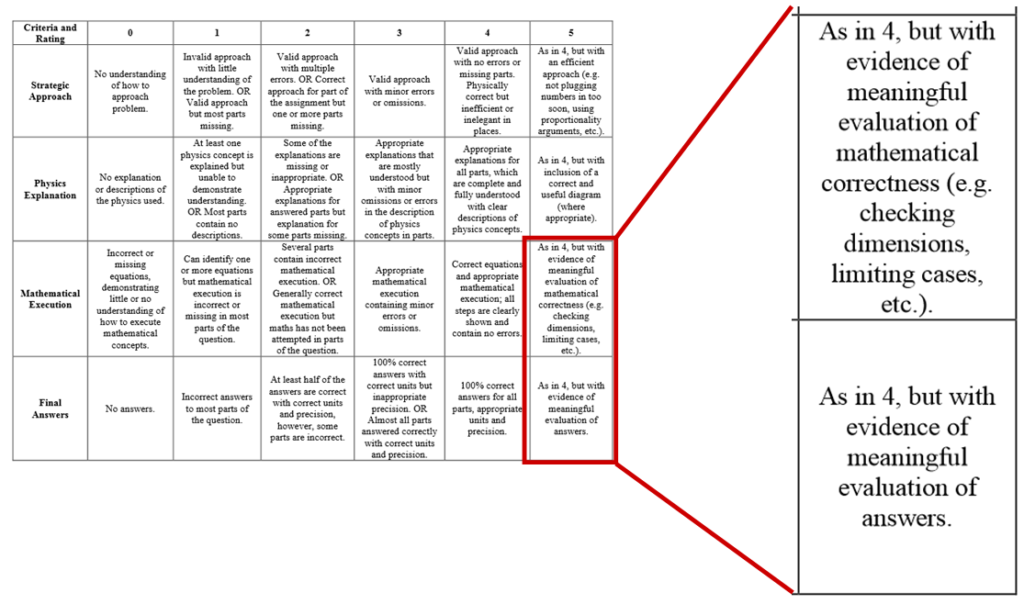

The context was Physics 1A: Foundations, the introductory physics course for which I am Course Organiser and one of the lecturers. Physics 1A is taught in a flipped classroom format, using a number of evidence-informed teaching strategies, such as Peer Instruction. As part of this environment, we used an assessment rubric, as shown below in Figure 1. This rubric was intended to allow us to assess the students’ submitted work on a number of criteria. But more than that, it is a well-observed phenomenon that what we assess drives student behaviour, so we attempted to use the rubric to promote expert-like behaviour. To obtain the highest available mark in each of the four criteria, students had to include in their assignments characteristics that are found in expert physicists’ solutions to problems. What a brilliant idea, eh? What could go wrong? Quite a lot, as it happens.

To illustrate how, I will discuss two of these expert-like behaviours that we sought to promote. The first involved checking the mathematical correctness of the students’ solutions. This might include making sure that equations have the same units on both sides of the equals sign (i.e. dimensional consistency). Or it might involve exploring what happens when some quantity in the equation becomes very big or very small, and confirming that the solution behaves sensibly in that case (i.e. limiting case or special case analysis). And this, the students dutifully did. Of course they did; they were getting marks for it, after all. But they didn’t do it in a worthwhile or actually useful way. See below for an example:

What the student has done here is perfectly technically correct. But it’s completely pointless. They’re checking the units of Einstein’s mass-energy relation. This is almost certainly the best-known equation in all of physics; you can stop random people in the street and they will know it. We’re pretty confident it’s valid, and there’s just no benefit in carrying out this process for it. The value of unit checks is for when you don’t recognise an equation, maybe because you’ve just worked it out for the first time while solving a problem, and need to judge whether it is a plausible solution or not. What the student is doing here is jumping through hoops.

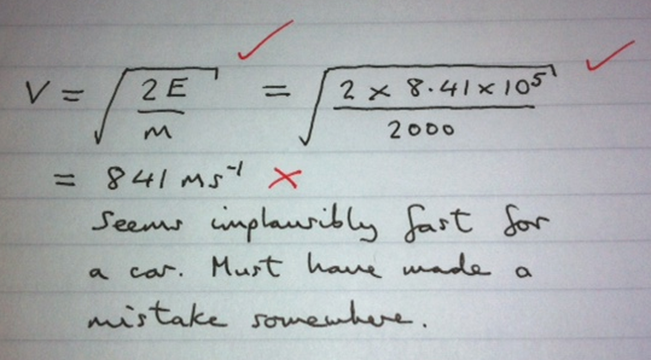

We observed related but subtly different problems with the other expert behaviour characteristics too. The second phenomenon I’ll mention here was that of students evaluating their final answers for plausibility, the so-called ‘sanity check’. For example, if you calculate that the mass of the Moon is 15 kilograms, you’ve definitely done something wrong… Did students do these evaluations? Yes. But again, look at how they did it:

In this example[1], the student is calculating the speed of a car, and finds that it seems to be travelling impossibly quickly (many times the speed of sound, in fact). The student has, perfectly correctly, observed that this seems implausibly fast, and that they must have made a mistake somewhere. They have indeed: just one line before the end, they forgot to take the square root. However, they handed in their work in this state anyway: they haven’t used the sanity check as a tool to improve their solution. They identified that there must be a mistake, but never actually attempted to track it down and correct it. More pointless and ineffectual hoop-jumping.

I don’t blame the students for this at all, and with hindsight we should have anticipated that this would happen. Our strategy with the rubric was firmly rooted in a behaviourist approach (“do as the expert does and all will be well”), and there are a number of potential pitfalls there, where students conform to the behaviour without appreciating or internalising the intent.

So what did we do? After a couple of years of frustration, we ditched this aspect of the assessment. However, we didn’t stop promoting these expert-like behaviours; we just tried to go about it in a more authentic manner. I model them during lecture sessions, and sometimes explicitly associate some assessment marks with carrying out these procedures, but only in cases where they are actually of unambiguous value. The intention now is to clearly illustrate not just what to do, but why we might actually want to do it.

Does it work? To some extent. I occasionally see some unit checking or limiting case analysis in the margins of exam script books. Not as often as I might like, but at least the students are now using the techniques as actual problem solving tools, as they are intended, and not as hoops to jump through. I’ll take that as a win.

[1] Sharp-eyed readers might notice a suspicious similarity to the handwriting in these two examples. I’m not picking on one poor individual; I re-wrote the examples myself to spare any potential blushes.