In this post, Dr Ross Galloway, Prof Judy Hardy and Tom Brown, from the School of Physics and Astronomy, share their insights into a research project exploring how an interactive engagement activity – the text-chat feature available in many software systems – effects student learning in live, online lectures. This post is part of the January and February Learning & Teaching Enhancement Theme: Online/hybrid enhancements in teaching practice.

When the Covid-19 pandemic required a switch to online modes of teaching, the School of Physics & Astronomy made a concerted effort to focus on synchronous (as opposed to pre-recorded) delivery of digital lectures, i.e where the lecture is delivered ‘live’ and students join the session in real time, via e.g. Zoom, Microsoft Teams, or Blackboard Collaborate. There were a variety of motivations for this decision, including a desire to maintain a sense of community, the structure that comes from regularly timetabled live sessions, but perhaps most importantly the intention to retain opportunities for ‘Interactive Engagement’ during lectures.

‘Interactive Engagement’ (IE) refers to a wide array of activities that could take place within a classroom setting. These activities are classed as “interactive” because they involve more than simply listening to and making notes on the content that the teacher is delivering. Examples of IE activities include students asking questions of the teacher, students discussing amongst themselves a particular problem, or a student being asked to present their solution to their peers.

Within the field of Physics Education Research (PER), and also more broadly within the field of scientific education research in general, there has long been a consensus that IE has an overall positive effect on students’ understanding of the subject matter [1]. However, almost all of this research was conducted prior to the widespread adoption of digital/online learning by universities throughout the world in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Whilst the overall aim of delivering a digital lecture and an in-person lecture are the same – namely that the students in attendance should come away having learnt something – the landscape within which they take place is very different. A key change in this landscape is the fact that many of the software systems used to deliver live, online lectures contain a text-chat feature that allows students to communicate with each other and the lecturer in a completely new way.

The chat feature in digital lectures allows students to not only to ask questions to which the lecturer, or in some cases a Teaching Assistant (TA), can respond verbally (as in the traditional in-person lecture) but, furthermore, it enables students to answer each other’s questions, discuss the material being covered in the lecture, and, in effect, the feature creates a secondary learning site within the lecture itself.

Part of the research done within our current project, which is still a work in progress, is to determine whether new forms of IE have emerged through the switch to digital teaching. Specifically, we have analysed transcripts of the text chats from a number of lectures to investigate the distribution of comment lengths, and the time sequence of comments. Figure 1 shows a representative timeline of a live, online lecture. The vertical axis of this plot shows the total number of characters entered into the chat by that time, whilst the horizontal axis shows how many minutes have passed since the lecture started.

As can be seen, the relationship between the two variables appears quite linear, evidencing that there is in fact a steady stream of comments being posted in the chat over the course of a lecture. This is not what we would expect from an in-person lecture: there, questions asked by a student to the lecturer would interrupt whatever else the lecturer was doing, and so tend to be relatively infrequent and localised. However, since the live chat in an online lecture is literally ‘on the side’, students can drop questions or comments in to it without having to attract the attention of or otherwise interrupt the lecturer.

We observe that lecturers tend to ‘keep an eye’ on the chat. They may respond right away to questions if they are immediately pertinent or requesting simple clarification or confirmation of something just said. Alternatively, they may ‘park’ them and respond at a more natural point in the lecture. Often, questions (particularly of confirmation) may be answered directly in the chat anyway by another member of the class (or a TA, if present).

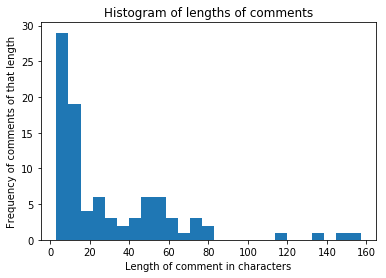

It can also be seen that there is a sharp spike in chat activity towards the very end of the lecture. This is driven overwhelmingly by students sending messages of thanks to the lecturer or saying goodbye. This is reflected by figure 2, a histogram which breaks down the text comments and classifies them by length. The first thing to note about this figure is that it is very strongly peaked at the lower end of the comment length axis. Clearly, the majority of comments in the chat are of relatively few characters, in most cases less than 20; these are mostly dominated by the ‘salutation’ comments at the end of the lecture. The figure clearly also shows that there are a non-negligible number of comments at the longer end of the spectrum (>50 characters). This evidences the fact that students will write lengthy and detailed questions (and answers) in the chat when they feel the need to do so.

Our initial findings suggest that the text chat allows ‘vicarious interaction’ [2] in an accessible way. Since students don’t have to ‘shout out’ or interrupt a lecturer in full flow, they may feel more able to ask questions, seek clarification, and respond to other students. Our study is now turning towards a focus on how the students experience and conceptualise this text chat interaction. Already, multiple lecturers have found it sufficiently informative and insightful enough that they are investigating tools to allow the ‘text chat on the side’ to remain in use, even when we return to more traditionally-situated, in-person lectures.

References

[1] https://www.compadre.org/per/items/detail.cfm?ID=12019

[2] https://journals.aps.org/prper/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.010140

Tom Brown

Tom Brown is currently in the final year of his Integrated Masters degree in Theoretical Physics, and is carrying out his final year project within the Physics Education Research Group on the topic of interactive engagement in digital lectures.

Ross Galloway

Ross Galloway is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Physics and Astronomy. He teaches on the undergraduate programmes in physics, and also conducts pedagogic research as a member of the Edinburgh Physics Education Research group (EdPER). His research interests include the development of student problem solving skills, diagnostic testing, and flipped classroom pedagogies.

Judy Hardy

Judy is Professor of Physics Education and Dean of Teaching and Learning in the College of Science and Engineering. Judy leads the Physics Education research group at the University of Edinburgh. Her research interests are in developing and evaluating evidence-based educational strategies that improve student learning in physics and related disciplines. She is particularly interested in the student experience of learning, teaching, assessment and feedback and in the ways that this can inform educational development.