![iStock [nambitomo]](https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/teaching-matters/wp-content/uploads/sites/7480/2017/10/iStock-500696260-nambitomo-1.jpg)

How are we doing, happiness-wise? Sometimes it’s hard to make sense of statistics on wellbeing. In the UK, during a period of economic and political turmoil, the four indicators of ‘personal wellbeing’ measured since 2011 have all shown steady improvements, including an overall decline in anxiety. You try telling that to University counsellors, personal tutors, and disability offices, who’ve seen their workloads skyrocket. According to the latest major review by the IPPR, there has over the past 9 years been a 400% increase in disclosure of mental illness by UK-domiciled first-year students. On many indicators, students seem to be faring worse than nonstudents. Boosting remedial care services is one necessary response, but in the long run strategies for optimising student and staff experience are crucial and they don’t need to be expensive.

Rather than get distracted by statistical debates, I’d like to propose here four basic principles that anyone with an interest in positive mental health and the quality of campus life should care about:

- Happiness is central to the processes and outcomes of good teaching. We are all co-responsible for one another’s happiness on campus and in the classroom. Everyone influences mental health, including not only lecturers, support staff, and students but those involved in timetabling, infrastructure, and accommodation etc. This matters both for its intrinsic value and as a means to ensuring effective learning.

- Happiness themes are great for interdisciplinary learning. Happiness or mental wellbeing is about people’s lives as wholes, and requires us to learn across various life domains. Happiness should be an important and explicit feature of many, perhaps even most subject areas because of its interest value and for its moral importance, as well as for its ability to encourage everyone to link their studies with personal experience.

- Happiness outcomes should be made explicit. The capabilities that students are supposed to acquire through university studies should equip them for effective lifelong pursuit of happiness, and for effective promotion of other people’s happiness.

- Both happiness and mental illness are contagious. Campus wellbeing and mental health strategies must be focused on everyone, not just on those suffering diagnosed pathologies. And happiness or mental flourishing must be part of all strategic conversations about mental health.

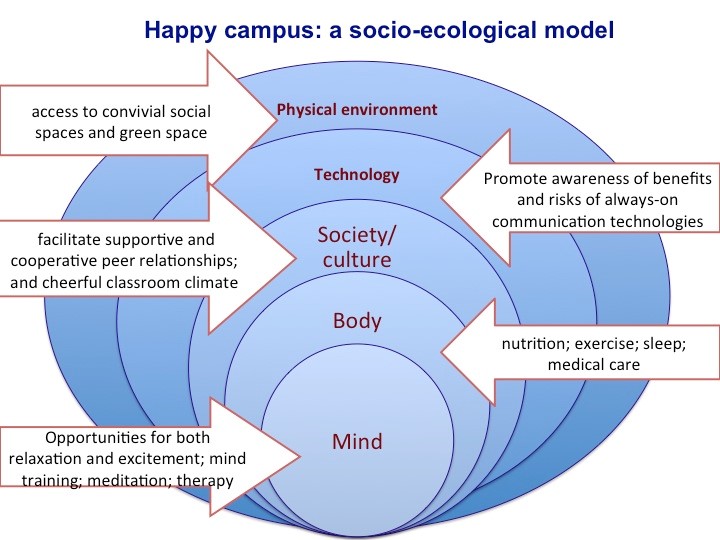

These points are easy to grasp, and easy to take action on since everyone is already experienced in the pursuit and promotion of happiness. The simple ecological model which we’ve used for our Student Mental Wellbeing Strategy helps us to think through the kinds of dynamic interaction involved in fostering and sustaining happiness:

Bearing in mind Dumbledore’s Law (‘fear of the name only increases fear of the thing referred to’) we should discuss mental illness and difficulties openly, and not use ‘mental health’ as a euphemism. If we are sincere about wanting to foster positive mental health throughout the whole campus community, we’d better talk openly about happiness too, and consider our many low-cost and no-regrets options for ensuring that the pursuit of excellence and the pursuit of social happiness work in harmony.