In this extra post, Dr. Omar Kaissi shares an inspiring example of how he incorporated Mattering – ‘the feeling of being recognised and of importance to someone’, into his personal tutor practice to support the mental health and wellbeing of his international students. Dr. Kaissi is a teaching fellow (MSc Education) at Moray House School of Education and Sport.

Mental health is a global emergency (refer to WHO Mental Health webpage for more details). According to ‘The University Mental Health Charter’, ‘the number of students [in UK universities] declaring a pre-existing mental illness … has more than doubled since 2014/15’ (Hughes & Spanner, 2019, p. 6), prompting universities to incorporate mental health and wellbeing provision into their ‘duty of care’.

The fundamental premise of ‘duty of care’ is that, beyond academic achievement, the twenty-first-century learner has multiple developmental needs (see Noddings, 2012), including mental health and well-being. If met adequately, these needs would culminate in what Riley (2009) calls ‘mattering’, that is, the student’s ‘feeling that [they are] recognised and represented as of importance to someone’ (Gravett & Winstone, 2022, p. 361). What is more, it is particularly in times such as these, when global crises – think the earthquake that recently hit Turkey and Syria – are seen to have a direct impact on individuals, that ‘mattering’ becomes all the more important.

To enhance my own understanding of mattering and incorporate it into my personal tutor practice, I took several professional development courses over the past three years. This proved invaluable, particularly to my sense of appreciation for the richness and diversity of students’ lives and backgrounds (e.g., socioeconomic, sociocultural, psychosocial, etc.). Indeed, from social class to language, to ‘race’, gender, and sexuality, if one pondered higher education, one would not fail to see majorities and minorities (and modalities of majoritisation and minoritisation) and, with respect to the latter, the need to realise certain fundamental rights to recognition, participation and protection against discrimination.

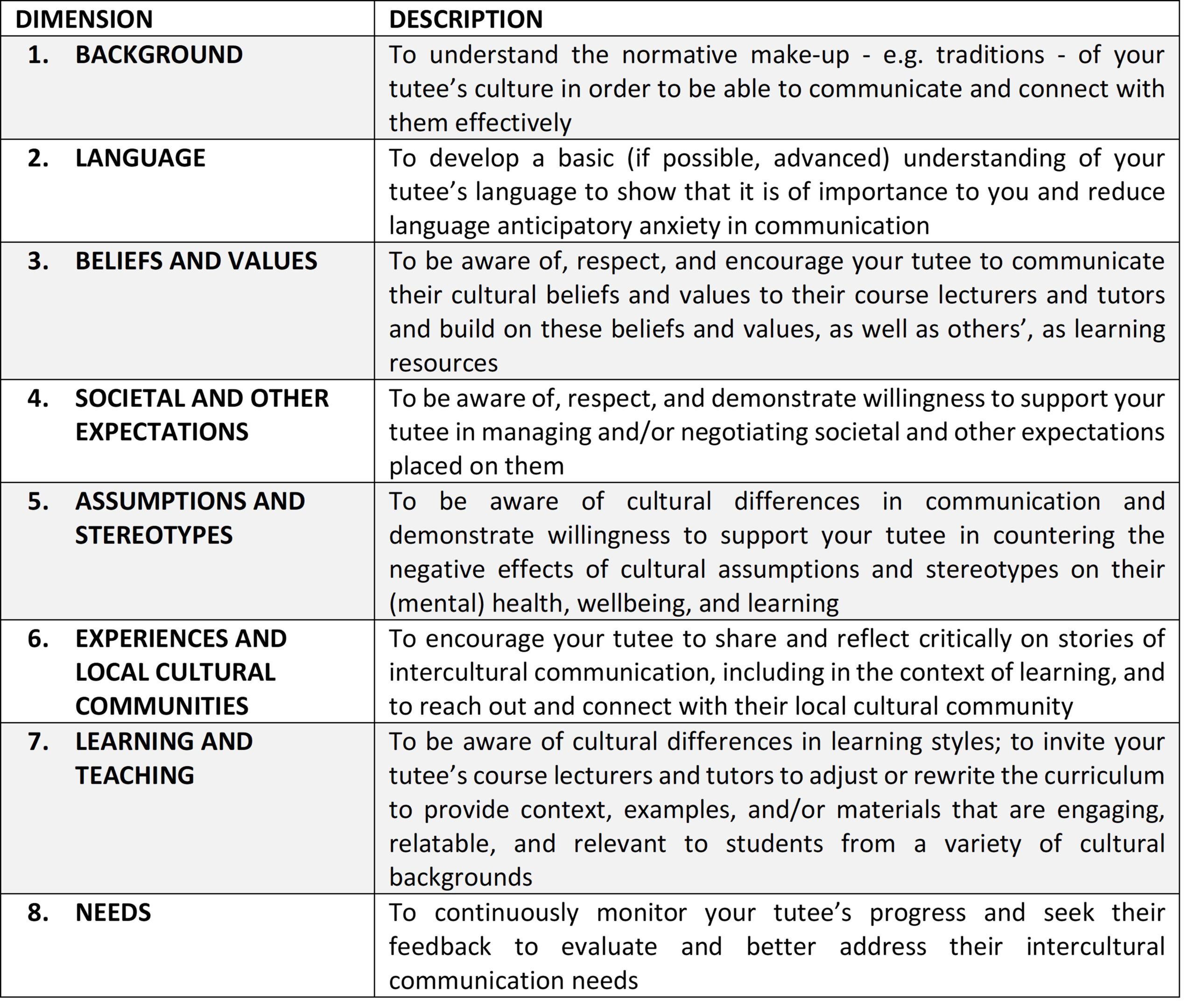

One such course was ‘Reflections on the Hidden Curriculum and its Impact on Working Class Students’ (June 2022) (listen to our Teaching Matters Podcast on this!). From it came the inspiration that, since the majority of my students are Chinese international students, one effective way to implement mattering, to show each student that they are ‘of importance’, is to create my own Culture-Sensitive Personal Tutor Checklist (CSPTC). As illustrated in the table below, my list places emphasis on interculturality and invites the personal tutor to engage in the rewardingly immersive experience of co-learning about the culture and cultural assumptive worlds of ‘the other’ – it is, if you wish, an invitation to practise other-ing as de-othering.

Table 1: A Culture-Sensitive Personal Tutor Checklist (CSPTC) for International Students

To ensure effective implementation of this CSPTC, I would use it in my first 1:1 meeting, devising leading questions and prompts as I go through it item by item. For example, applying item (2), I would begin by asking the tutee such questions as: ‘Have you done any writing in the English language before? I am aware that different languages have different writing conventions. I can tell you about Arabic, my first language. Do you think you can tell me about Mandarin, perhaps, and how writing in Mandarin is different from, say, English?’ Moreover, to identify and act on needs, in accordance with item (8), I would follow up on this first meeting by continuing to use my CSPTC in subsequent meetings. For example, last year, one of my tutees shared her concern that a course tutor might interpret her silence in workshops as a sign of wilful disengagement or, worse, disrespect. This issue had been on her mind for a long time, exacerbating her learning in an intercultural setting anxiety, which I had noted under item (5), ‘Assumptions and stereotypes’, in our first meeting. In response, I firstly clarified that it is a stereotype in Western-oriented (higher) education to render silence a deterrent to effective learning (see Wang et al., 2022), and, secondly, I wrote to her course tutor to bring the issue to their attention. The outcome was that, weeks later, my tutee disclosed that she no longer had ‘bad feelings’ about her silence. Following her tutor’s advice, she had stepped up her contribution to weekly asynchronous activities as a way to compensate for in-class participation.

The crucial bit in Riley’s (2009) concept of ‘mattering’ is not that students should be made to feel ‘of importance’, but rather that they should feel important ‘to someone’. That someone is no-one but me, their teacher. Thus, as part of enhancing future applications of my CSPTC, I plan to invest in story-telling approaches. Sharing my own stories as a former international student in the UK would help portray me more credibly as someone who cares, who recognises their students as significant others in their life.

References

Gravett, K., & Winstone, N. E. (2022). Making connections: Authenticity and alienation within students’ relationships in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(2), 360-374. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1842335

Hughes, G., & Spanner, L. (2019). The university mental health charter. Leeds: Student Minds. https://www.studentminds.org.uk/uploads/3/7/8/4/3784584/191208_umhc_artwork.pdf

Noddings, N. (2012). The caring relation in teaching. Oxford Review of Education, 38(6), 771-781. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2012.745047

Riley, P. (2009). An adult attachment perspective on the student-teacher relationship and classroom management difficulties. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(5), 626-635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.11.018

Wang, S., Moskal, M., & Schweisfurth, M. (2022). The social practice of silence in intercultural classrooms at a UK university. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 52(4), 600-617. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1798215

OMAR KAISSI

OMAR KAISSI

Dr Omar Kaissi is a Teaching Fellow (MSc Education) at Moray House School of Education and Sport, The University of Edinburgh. His research interests are the sociology of education and the politics of education. He is co-convenor of the Higher Education Research Group (https://www.ed.ac.uk/education/rke/our-research/teacher-curriculum-pedagogy/herg). He is member of the British Educational Research Association and the Lebanese Association for Educational Studies. Omar’s Arabic blog (https://omarkaissi.blogspot.com/?m=1) features in-depth critical reflections on politics, society, culture and education in Lebanon.

Such a beautiful, thoughtful and powerful piece, and structure, for improving student (and staff) experience . And love the evidence-based, practical approach that is creating a replicable model for others to also use to increase impact – thank you for sharing.

You’re most welcome, Lucy.

This is just what I had to read as concept of mattering matters to me (no pun intended), especially in health science discipline that incentivises outcome based approach although most of the education policies and procedures are products of neo liberal agenda. Being an international student (non traditional) on Clin ed this was so heart warming to read and see tutors actively making a difference because it matters. Just one step makes such huge butterfly effect. Being valued versus being valued for performativity is a thin red line violated sometimes unintentionally. Tq amazing read

You’re most welcome, Avita.

This read helps to understand those views that are different perhaps from our own and I find it inspirational!

Nice piece Omar. We’re soul brothers – care before content expertise. It’s care for the soul. It’s what the world needs more of.