Higher education in the UK is experienced differently by our diverse student cohorts. Our mature undergraduate students are significantly less likely to complete their degree than their younger counterparts; students with disclosed disabilities are less likely to receive upper degrees than those without; students from higher socio-economic classifications are more likely to receive upper degrees than those from lower classification; our white students are more likely to be in full-time work six months after qualifying than our black and minority ethnic students; and certain subjects still exhibit extreme imbalance in relation to gender make-up. We advocate the adoption of inclusive practice to ameliorate these differences.

Vicky Gunn: Conceptualising the disciplines’ role in inclusive teaching practice

Higher Education needs to foster disciplinary sameness and transformation simultaneously. This paradox is at the heart of learning and teaching in universities, colleges, Art Schools and Conservatoires. When it comes to inclusive environments in this context, we need to reflect on two key but complex questions about the how of teaching:

- What disciplinary conditions advance learning for all students once they are enrolled into its study?

What do our answers to this question mean in the light of an aspirational agenda around inclusion in which we are asked to recognise that difference in equality is at once both fixed and fluid? And how do the traditions of our teaching practice represent social norms and dominant social groups in a manner that excludes as well as lowers the potential for creative abrasions to grow the disciplinary canon?

- How do we challenge our students to learn to the best of their ability without alienating them (because the way we challenge implies that they are failing because of who they are in socio-cultural terms and where they have come from rather than from the perspective of building expertise in a discipline)?

Behind this reflective question are a series of propositions. Each one is contentious, but worthy of reflection:

- Academic thinking and being are not always aligned. Academics make critical judgements about disciplinary phenomena, but at the same time operate uncritically from within ideological positions that restate social norms being challenged in equalities’ conversations (and regulations).

- Disciplines transcend and do not transcend normative culture. We tend to accept disciplines are not neutral spaces, but do not acknowledge what this means in terms of students’ learning experiences.

- If disciplinary teaching environments are not culturally neutral, how does this impact on minority group student learning?

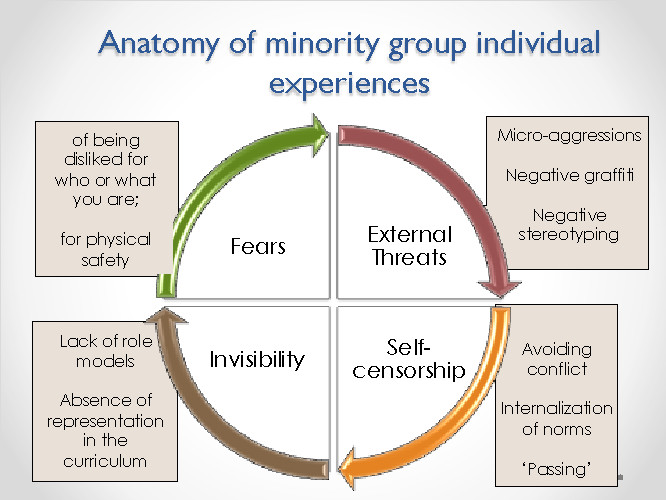

In the report Equality and diversity in learning and teaching in Scotland’s universities (2015, p.40), I outlined an anatomy of minority student experience thus:

This was to describe how the amplification of tensions related to being spoken of as ‘other’ or discriminated against takes up minority group student energy. This amplification can provoke alienation and apathy (disengagement) but, if well managed through inclusive curricula, it can also generate agency of thought within the disciplines. If there were no other good reasons to develop inclusive teaching and learning practices, surely the provocation of innovative and original critique of disciplinary canons is a valuable academic one?

Pauline Hanesworth: Thinking about the practical implications

So what does this mean in practice? The Higher Education Academy encourages an approach to inclusive curricula comprising four underpinning principles:

- Interrogate your disciplinary norms. What are our disciplinary practices that represent social norms and dominant social groups? Who and what are we othering in this normatisation? How can we vary our teaching and assessment practices to balance normatisation and marginalisation and to encourage the active participation of all our students? Fundamental to this is an assessment of assumptions – linguistic (e.g. what level of competence in disciplinary language do we assume our students have?), experiential (e.g. upon what experiences – personal, academic, cultural – do we predicate our teaching?) and practical (e.g. of what level of disciplinary knowledges and practices do we assume our students have experience?).

- Teach to nurture student belonging and engagement. To militate against the alienation and apathy that normatising can create, we can ensure our teaching works to facilitate student belonging and engagement. This means paying attention to environment: to what extent do we create safe and collaborative learning spaces conducive to student learning? This does not mean mollycoddling our students, but understanding that learning and engaging with difference can be uncomfortable. We must create environments in which our students are comfortable in this discomfort and so best able to learn. This means also paying attention to pedagogy: to what extent do we work with our students as co-creators and co-producers of the learning experience, empowering them to take responsibility for their own, and each other’s, learning and enabling them to connect their lived experiences to disciplinary contents?

- Interact with diversity through learning and teaching. To what extent do we create practices and environments in which students are exposed to and are tasked with better understanding cultures and ways of being with which they might not be familiar? Such activity does not just enable students of a variety of backgrounds to recognise themselves in their curriculum content, but also encourages our students to develop their critical thinking by exploring different ways of thinking and being. This is best done not as an add-on approach, but infused within curriculum content – e.g. by integrating themes of equality, diversity and cultural relativity into materials (how visibly diverse are the images and examples we use?), activities and content (how diverse is our source material?). And infused within pedagogies – e.g. by providing opportunities for students to share their diverse experiences, voices and learning, and relating these to the curriculum content, and by manufacturing interactivity so students can learn from working with their outgroups.

- Encourage and practice self-reflection. Just as our disciplines are not neutral, neither are we. We are human, with our own backgrounds, experiences, unconscious – and conscious – biases and assumptions. These impact not only on who, what and how we teach – creating hidden curricula – but also who, what and how we learn. Further, these influence our very understanding of what Knowledge, Learning, Teaching and Education is (and is for). We must shine a critical light on these, understanding their implications for our own teaching practices. We must also be honest about these with our students, encouraging them to reflect on their own identities and backgrounds, and how these influence who they are and how they act in both their disciplinary and wider worlds.

By bringing inclusive practice into the heart of our disciplinary practices we can, then, enrich not only our students’ learning experiences but also our understanding and shaping of the disciplines themselves.

Further reading:

Barnett, P. E. (2011) Discussions across difference: addressing the affective dimensions of teaching diverse students about diversity. Teaching in Higher Education. 16 (6), 669-679.

Burke, P. J. and Crozier, G. (2012) Teaching inclusively: changing pedagogical spaces. Higher Education Academy.

Gibson, S. (2015) When rights are not enough: what is? Moving towards new pedagogy for inclusive education within UK universities. International Journal of Inclusive Education. 19 (8), 875-886.

Gunn, V., Morrison, J. and Hanesworth, P. (2015) Equality and diversity in learning and teaching at Scotland’s universities. Higher Education Academy.

Hanesworth, P. (2015). Embedding equality and diversity in the curriculum: a model for learning and teaching practitioners. Higher Education Academy.

Hockings, C. (2010) Inclusive learning and teaching in higher education: a synthesis of research. Higher Education Academy.

Thomas, K. (2015) Rethinking belonging through Bourdieu, diaspora and the spatial. Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning. 17 (1), 37-49.

Varia (2015) Embedding equality and diversity in the curriculum: discipline-specific guides. Higher Education Academy.

This article highlights the importance of adopting inclusive practices in higher education teaching to address the disparities and inequalities experienced by diverse student cohorts. It acknowledges the challenges faced by mature students, students with disabilities, students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, and minority ethnic students.

This article serves as a valuable resource for educators and institutions committed to creating a more inclusive and diverse higher education landscape. It encourages critical reflection and offers practical suggestions for implementing inclusive teaching practices.