In this post, Kirstin Stuart James discusses a framework that shows how academic activities like teaching and learning can either support or undermine our health and overall well-being, using a model by Eklund et al. (2017)↗️. This post belongs to the Hot Topic series: Through the Lens of Occupation↗️.

Linking back to the previous blog↗️, occupations are intrinsically linked to human health and wellbeing. To better understand and theoretically underpin this relationship, occupational science developed as a discipline in in the 1990s, led by Yerxa and others (see for example Yerxa, 1993↗️). Occupational scientists strove to bring a research-informed theoretical framework to occupation and therefore critically examine how occupation supports (or negatively impacts) health. From this work, balance across embodied and situated daily occupations is the central mechanism to understand what brings a sense of wellbeing and purpose to one’s lifeworld.

This blog is by no means the first-time occupation has been linked to pedagogy. In her imaginary letter, Magalhães (2012, p8)↗️ asked “what would Paulo Freire think of occupational science?” and posited the importance of praxes in actualising Freire’s emancipation through pedagogy (Freire, 1996↗️). Praxes is already a way to understand the embodied practices (or ‘doings’) of learning and teaching (as shown in the cover image), linking back to Aristotle’s philosophies of praxis (practice) and poesis (outcome/product) (Suriano, 2022; Balaban,1990↗️).

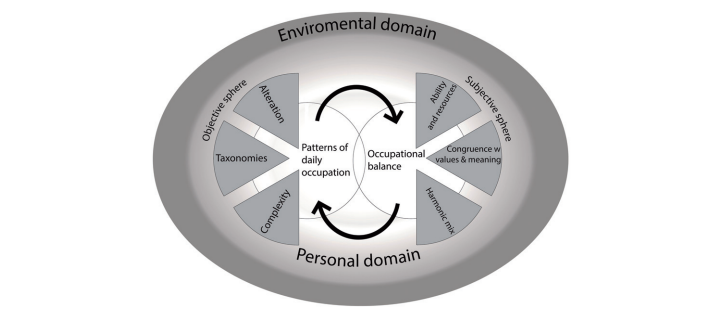

However, a pedagogical lens of occupation goes one step further and relates human health (positive and negative) with the praxis and poesis of education. Figure 1 shows one (tentative) theoretical model developed by Eklund et al (2017)↗️ to conceptualise what balance might ‘look like’ across embodied occupations situated in the social world. This blog series applies Ekland et al’s model to the everyday occupations associated with teaching and learning in Higher Education (HE) to explore, pedagogically, how they might link to health.

Applying Ekland et al’s (2017)↗️ model, ‘Environmental domain’ is the physical, environmental, social, and political contexts in which HE occurs, while ‘Personal domain’ is the teacher or learners’ personal engagement with the occupations involved in teaching and learning. The ‘Objective sphere’ captures patterns of the daily (everyday) occupations involved in teaching and learning, for example, lecturing, designing, teaching, marking, collaborating, pastoral support and the myriad other activities teachers and learners ‘do’.

Ekland et al (2017)↗️ suggest the patterns of daily occupations can be altered (‘Alteration’) by, for example resources available at the macro- or meso- level, and by population health challenges on the ability or capacity to ‘do’. ‘Complexity’ indicates exactly that, determined by, for example, whether the occupation needs others to perform it, its occurrences in a temporal sense and its singular or multi- dimensionality. ‘Taxonomy’ then ‘sorts’ occupations into archetypes of activity, categorised as early as 1922 (Meyer, 1977↗️) as the occupations associated with ‘work, play, rest and sleep’.

While occupations in teaching and learning appear primarily as activities of ‘work’ they sit in balance with other occupations, with the potential therefore to impact ‘sleep, play and rest’.

This potentiality moves the orientation of Ekland et al’s model to the ‘Subjective sphere’ and how occupations sit in harmony (‘Harmonic mix’) with each other. Occupational dysfunction (Hammell, 2015) means the ‘harmonic mix’ is over- or under-loaded in activity, leading to occupational imbalance (Teraoka and Kyougoku, 2015↗️) with resultant negative consequent impacts from occupational deprivation (limitations to engagement), occupational alienation (engagement becomes meaningless), and/or occupational marginalisation (autonomy and agency are lost) which can all impact mood, health, and wellbeing (Teraoka and Kyougoku, 2015↗️).

Staying in the ‘Subjective sphere’, ‘Abilities and resources’ closely link with ‘Alteration’ in the ‘Objective sphere’, but this time the focus is on individual rather than collective ability to participate in occupations. Impacts come from, for example, reduced engagement in activity due to, for example, ill health, and/or availability of personal resources such as secure housing, access to monetary funds and social support networks that promote occupational engagement. Finally, ‘Congruence with values and personal meaning’ (mis)aligns occupations with personal and moral values; engaging meaningfully in chosen occupations brings with it the potential for value and purpose in the lifeworld.

While Ekland et al (2017)↗️ have been clear their model does not claim a causative relationship between the domains and spheres of occupation and human health, linking back to Blog 1↗️, Wilcock affirms “the notion that occupation influences people’s health extends far back into human history” (2001, p20↗️). Therefore, it makes theoretical sense that impacts from practices in teaching and learning related to the domains and spheres of occupation have the potential to influence health and wellbeing.

A pedagogical framework for occupation therefore contends that the practices of teaching and learning, associated outcomes, and the contexts in which this takes place, has the potential to both support and undermine wellbeing and health. Building on this concept, the next blog will explore ‘taxonomies’ of activity in teaching and learning, before looking at two of the potentially biggest disruptors to contemporary HE, artificial intelligence, and sustainability.

References

Balaban, O. (1990). Praxis and Poesis in Aristotle’s practical philosophy↗️. The journal of value inquiry, 24(3), pp.185-198.

Eklund, M., Orban, K., Argentzell, E., Bejerholm, U., Tjörnstrand, C., Erlandsson, L.K. and Håkansson, C. (2017). The linkage between patterns of daily occupations and occupational balance: Applications within occupational science and occupational therapy practice↗️. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy, 24(1), pp.41-56.

Foreman, K.J., Marquez, N., Dolgert, A., Fukutaki, K., Fullman, N., McGaughey, M., Pletcher, M.A., Smith, A.E., Tang, K., Yuan, C.W. and Brown, J.C. (2018). Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016–40 for 195 countries and territories. The Lancet, 392(10159), pp.2052-2090.

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (revised)↗️. New York: Continuum, 356, pp.357-358.

Hammell, K.W. (2015). Participation and occupation: The need for a human rights perspective. Canadian journal of occupational therapy, 82(1), pp.4-5.

Magalhães, L. (2012). What would Paulo Freire think of occupational science?↗️. Occupational science: Society, inclusion, participation, pp.8-19.

Meyer, A. (1977). The philosophy of occupation therapy↗️. Reprinted from the Archives of Occupational Therapy, Volume 1, pp. 1–10, 1922. Am J Occup Ther. 1977;31:639–642

Raghupathi, V. and Raghupathi, W. (2020). The influence of education on health: an empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995–2015. Archives of public health, 78(1), pp.1-18.

Saarinen, T. and Ursin, J. (2012). Dominant and emerging approaches in the study of higher education policy change. Studies in Higher Education, 37(2), pp.143-156.

Suriano, B. (2022). Praxis as the unfolding of poiesis: Renewing the normativity of labor for critical theory↗️. Philosophy & Social Criticism, p.01914537221122370.

Teraoka, M. and Kyougoku, M. (2015). Development of the final version of the classification and assessment of occupational dysfunction scale↗️. PLoS One, 10(8), p.e0134695.

UNESCO (2022). Right to Education Initiative. London: Right to Education Initiative.

Whiteford, G.E. and Pereira, R.B. (2012). Occupation, inclusion and participation. Occupational science: Society, inclusion, participation, pp.187-207.

Wilcock, A.A. (2001). Occupation for health: Re-activating the Regimen Sanitatis↗️. Journal of occupational science, 8(3), pp.20-24.

Yerxa, E.J. (1993). Occupational science: A new source of power for participants in occupational therapy↗️. Journal of occupational science: Australia, 1, 3–9.

Kirstin Stuart James

Kirstin Stuart James

Dr Kirstin Stuart James is currently on secondment as Deputy Programme Director within the Clinical Sciences Teaching Organisation, part of the College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine at University of Edinburgh. As her substantive post, Kirstin is Senior Academic Coordinator/MSc Year Lead in Clinical Education where she teaches on online distance learning programmes for those involved in undergraduate and postgraduate education across the health and veterinary professions. She is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. Kirstin is also a Senior Occupational Therapist in Urgent and Emergency Care with NHS Lothian. Kirstin is interested in the links between health and education, and how an understanding of occupation and occupational therapy can enrich teaching, learning and educational design, and support health though education. You can find Kirstin on Twitter (X) at @TherapyStatim↗️.