For this Spotlight on Remote Teaching post, Dr Yahya Barry, Teaching Assistant and Research Fellow at Edinburgh’s Alwaleed Centre, discusses how Islamic law has responded to state-enforced social isolation measures in the wake of the Covonavirus pandemic. These questions will be explored further in the free online course The Sharia and Islamic Law: An Introduction, relaunching on 11 May 2020…

Coronavirus has come and, with sheer draconian force, seemingly suspended all communal activity across the globe. While entire socio-economic systems are left starving and the furloughed struggle with food and utilities, others are feeling the strain of social isolation and loss of community.

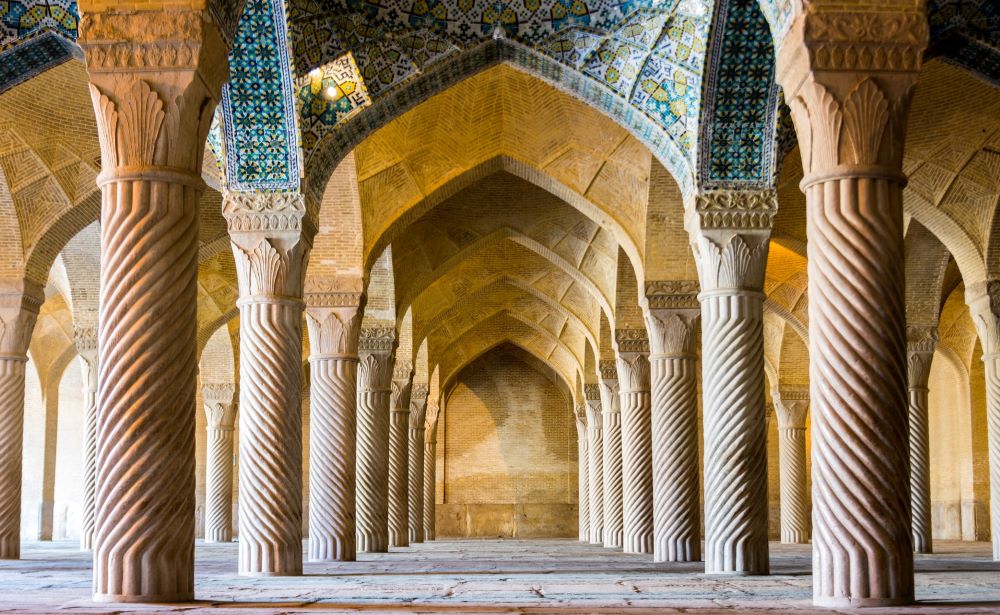

Islam is often viewed from the outside as quite a pedantic religion, both in terms of ritual but also, and most relevant to the current predicament, in terms of its approach to congregational worship. A stark warning exists in its canonical texts concerning the abandonment of the Friday congregational prayer (Jama`ah in Arabic), with observance of the prayer in communal settings elevated as a marker of true faith. What happens to this community of believers, along with their faith, when they can no longer physically meet to worship together in prayer, fasting, celebration and mourning?

This is where the Sharia and Islamic law come in…

I shall start with a WhatsApp group of Imams in Edinburgh, of which I am a part, discussing what to do when, as a response to an official letter from the Scottish government urges them to “suspend congregational prayers within the Mosque – including the Friday prayer”. While Islam has a set of clearly outlined ordinances – the Sharia – these Imams now have to delicately juggle multiple contingencies: the immediate risk to health, the demographic reality of a dispersed and diverse minority community (1.45% as per the last census) and the fact that their jurisdiction and authority has to operate within the confines of secular Scots law. As religious leaders, the Imams may have the authority to advise their communities on when to start and finish their prayers or when they should begin and end their fast. Some are even celebrants able to officiate marriages in their mosques under both Islamic and Scots law. Yet, here we are, being urged by the Cabinet Secretary for Justice, Humza Yousaf – a Muslim himself – along with the Chief Medical Officer to cancel all prayer in congregation.

The WhatsApp discussion starts with a number of key points of debate. Some of the Imams question the linguistic and perhaps technical connotations of the word “urge” alongside its legal significance in the letter. “Urge”, says one, “that’s surely not an obligation or a command?” Another highlights that the term is nevertheless qualified with the adverb “strongly”. Another critically dissects the warrant behind the urge: protection of the NHS here is seemingly a point of conjecture, not one of certainty. Could prayers be cancelled on the grounds of statistical predictions? A reminder is then served: in Islamic law, “certainty” (Yaqeen) can only be removed by certainty, not conjecture. Distinctions were starting to emerge now between the classically trained Imams from the seminaries in contrast to the more eclectically qualified members of the group. Another interjects at this point, reminding the group of the certainty embodied in the sanctity of the mosques – they are symbolic of the community’s identity and wellbeing. “But this is a matter of life and death” retorts another, referencing the fact that the removal of harm (Mafsadah) supersedes the good or virtue (Maslahah) of communal practice – a legal maxim rooted in Sharia which emerges as authoritative during the discussion. This, along with information cited from Muslim advisory groups affiliated to the Muslim Council of Britain and the Muslim Council of Scotland, Fatwas from certain global authorities and consultations by Qadis (Islamic judges) from across the Muslim world, seals the outcome.

Within three hours all fourteen mosques in Edinburgh represented by the group announce the cessation of communal worship, except one – there’s always one. But even this mosque later reconsiders its position and adopts the same stance as the majority.

This informal WhatsApp group of Imams, now representing a population of 15,000 Muslims across the city of Edinburgh, deliberated over matters as though they were a legal council, sitting in order to pass important juristic matters of policy. And, in many ways, they were. Within an hour or two of our WhatsApp deliberations, Facebook posts, emails and tweets appeared communicating the cessation of congregational worship. The Friday congregational prayers were to be replaced by the normal afternoon prayer as there was no precedent to instruct that the same format be undertaken at home during times of social isolation.

This brief vignette shines a light on the contextual, debated and constantly evolving nature of Islamic law – particularly in Muslim minority contexts where authority dictates that the law of the land must take precedent at all times.

The religion of Islam – often a reified, homogenized, politicized and misappropriated religion in the West – has existed for over 14 centuries. While its mediated image often conjures up in the popular mind a somewhat dogmatic, ultra-structured, hyper-visible approach to faith, practice and community, little is known about the way its code of legislation (the Sharia) actually operates for its almost 2 billion followers who invariably cherry pick, syncretise, and “mix and match”, creating a bricolage of Islams across the world’s religious ecosystems and landscapes.

So how do individual Muslims understand God’s law? Is there a difference between the letter of the law and its spirit? Which authorities are qualified to interpret, implement and police it? In the contemporary, globalised world we live in, what happens when Muslim communities find themselves in secular contexts on the one hand or are caught up in the midst of attempts to recreate a society ruled and governed by the Sharia on the other? Is there a difference between the Sharia (in Arabic, the pathway defined by God, an ideal) and Fiqh (Islamic law, a human effort to interpret Sharia)?

These are some of the questions that our free, 5-week online course The Sharia and Islamic Law: An Introduction will interrogate. Designed by leading academics from the University of Edinburgh specialising in Islamic and Middle Eastern studies, anthropology, politics, religious studies, sociology and theology, this course brings together multiple perspectives to guide the enquiring mind in this often very misunderstood subject.

OTHER USEFUL RESOURCES:

- Information Services Teaching Continuity web pages

- New guidance for students on using online learning tools

- Assessment Continuity webpages on the Information Services website

- University of Edinburgh online courses on FutureLearn