In this blog post, Kirstin Stuart James discusses the potential health threats posed by the displacement of meaningful teaching occupations and advocates for a rights-based approach to ensure equity and inclusion in the AI-driven educational landscape. This post belongs to the Hot Topic series: Through the Lens of Occupation↗️.

As introduced in previous blogs, occupational disruption occurs when there is an “inability to participate, or participate fully, in chosen occupations” (Nizzero, Cote, and Cramm, 2017, p123)↗️. In Higher Education (HE), this means disruption to participation in the occupations of teaching and learning. Nizzero, Cote and Cramm go further and relate the consequences from occupational disruption, including disruption to “identity and social, emotional, and occupational function(ing)” (2017, p124)↗️, to negative impacts on health.

Disruptive technologies are not new to the HE context (see Flavin, 2017↗️, for example) however 2023 was claimed across media as the ‘breakout year’ for Artificial Intelligence (AI) (FT, 2023)↗️. AI in education, already has a broad historical and research context, and multiple existing current usages as teaching tools and applications examining learning activity (Williamson and Eynon, 2020)↗️.

Although “definition elusivity” (Krafft et al, 2020, p72)↗️ is a term often applied to AI due to its multiple and ‘ambiguous’ applications, here it is taken to simply mean machine intelligence developed to perform actions usually undertaken by humans. However, despite long standing applications, 2023 sent the academic community into ‘AI-shock’ as “considerable epochal hype and hope, as well as dystopian dread” (Williamson and Eynon, 2020, p223)↗️ followed the further acceleration of AI into education-focused applications, not least ‘text-generative’ AI, especially ’Chat-GPT’ (OpenAI, 2023; Bozkurt, 2023)↗️.

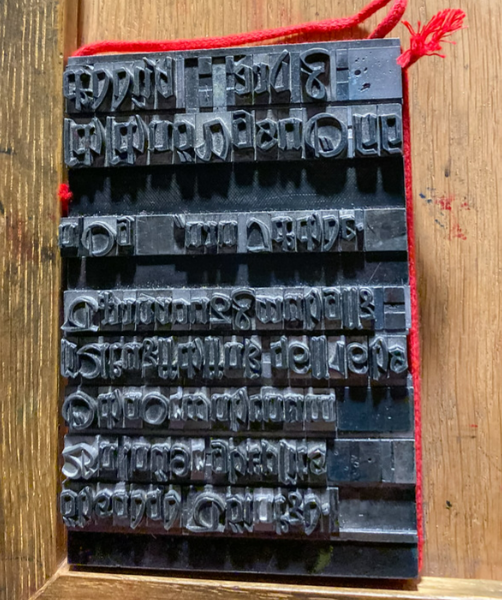

A flurry of academic responses to the arrival of Chat-GPT made comparisons to previous technological revolutions in human history (see for example Peters et al, 2023)↗️, including the introduction of the Gutenberg printing press (Figure 2) which prepared the ground for mass production of communications (Füssel, 2001)↗️. While the potential for all the positive and negative impacts of AI in education are beyond the scope of this series, the response to the rapid uptake of ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2023)↗️ ushered in a new epoch in HE and it merits reflection why this tool seemed to strike such a chord.

Linking back to Blog 1↗️ and Finlay’s claim that “we are what we do’’ (Finlay 2004, p10)↗️, perhaps this rapid uptake caused academics to question their very identities as teachers; if generative AI tools were able to perform and appear to ‘do’ many of the everyday occupations previously associated with teaching, then ‘what are we’? As above, Nizzero, Cote and Cramm (2017)↗️ claim disruption in occupations links to disruption in personal identity. It is not only the threat to job and economic security, but the change in self-perception of role and self-concept of what it means to be a teacher that might be causing concern. In addition, differences in mastery and literacy in AI technologies also brings potential for marginalisation for those without access to and knowledge of digital technologies.

Meaning and purpose are central constructs in occupational science. An accumulating evidence base extrinsically links a sense of purpose to human health (see for example Kim et al, 2020)↗️. Threats to occupations that are meaningful and purposeful in teaching posed by AI in education tools, for example, mastery of knowledge, skill in setting assignments, curriculum design and relationality of teaching could lead to feelings of displacement, marginalisation, and result in threats to health.

While the ongoing impacts of AI in education are still being realised, a future vision of AI in Education could be a rights-framed approach of occupational justice in teaching and learning. The World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT) has a fundamental position that “we deplore action that denies access to the human right to participate in chosen occupations which are the foundation of just and inclusive societies” (WFOT, 2022)↗️. Much work is yet to be done to bring a future vision of AI in Education with equity of opportunity and access to AI, but rights to meaningful and purposeful occupations in teaching without exclusion are essential.

This future vision aligns with UNESCOs aims “to maximize the benefits of the scientific discoveries, while minimizing the downside risks, ensuring they contribute to a more inclusive, sustainable, and peaceful world” (UNESCO, 2023, online source)↗️. Digging a little deeper, looking to both UNESCO (Miao and Holmes, 2023) and United Kingdom (UK) Department of Education statements related to the adoption of AI in education, neither explicitly mention the potential for benefits and threats to health from AI (Department of Education, 2023)↗️. As this blog series↗️ has suggested this link, policy should also take the opportunity to examine and protect threats to health from the mass adoption of AI into HE. The next blog also looks at threats to health, but this time from a sustainability perspective.

References

Bozkurt, A., Xiao, J., Lambert, S., Pazurek, A., Crompton, H., Koseoglu, S., Farrow, R., Bond, M., Nerantzi, C., Honeychurch, S. and Bali, M. (2023). Speculative futures on ChatGPT and generative artificial intelligence (AI): A collective reflection from the educational landscape↗️. Asian journal of distance education, 18(1).

Department of Education (2023). Policy Paper: Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Education. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/generative-artificial-intelligence-in-education/generative-artificial-intelligence-ai-in-education↗️ [Accessed: 26 November 2023]. October 20

FT (2023). A breakout year for artificial intelligence↗️. London: The Financial Times Limited

Finlay, L. (2004). The Practice of Psychosocial Occupational Therapy↗️. Cheltenham, Nelson Thornes Limited. Third Edition.

Flavin, M. (2017). Disruptive technology enhanced learning: The use and misuse of digital technologies in higher education↗️. Springer.

Füssel, S. (2001). Gutenberg and today’s media change↗️. Publishing research quarterly, 16(4), pp.3-10.

Kim, E.S., Shiba, K., Boehm, J.K. and Kubzansky, L.D. (2020). Sense of purpose in life and five health behaviors in older adults↗️. Preventive medicine, 139, p.106172.

Krafft, P.M., Young, M., Katell, M., Huang, K. and Bugingo, G. (2020). Defining AI in policy versus practice↗️. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (pp. 72-78).

Miao, F. and Holmes, W., (2023) Guidance for generative AI in education and research, UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. France. Available: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/6942367/guidance-for-generative-ai-in-education-and-research/7852269/↗️ [Accessed: 26 Nov 2023]

Nizzero, A., Cote, P. and Cramm, H. (2017). Occupational disruption: A scoping review↗️. Journal of occupational science, 24(2), pp.114-127.

OpenAI (2023). ChatGPT. Available: https://chat.openai.com/↗️ [Accessed 26 November, 2023].

Peters, M.A., Jackson, L., Papastephanou, M., Jandrić, P., Lazaroiu, G., Evers, C.W., Cope, B., Kalantzis, M., Araya, D., Tesar, M. and Mika, C. (2023). AI and the future of humanity: ChatGPT-4, philosophy and education–Critical responses↗️. Educational philosophy and theory, pp.1-35.

UNESCO, 2023. Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. Available from: https://www.unesco.org/en/artificial-intelligence/recommendation-ethics↗️ [Accessed: 26 November, 2023].

Williamson, B. and Eynon, R. (2020). Historical threads, missing links, and future directions in AI in education↗️. Learning, media and technology, 45(3), pp.223-235.

World Federation of Occupational Therapists (2022). Public Statement: Right to Access Occupations. Available from: https://wfot.org/news/2023/public-statement-right-to-access-occupations↗️ [Accessed: 26 November 2023].

Kirstin Stuart James

Kirstin Stuart James

Dr Kirstin Stuart James is currently on secondment as Deputy Programme Director within the Clinical Sciences Teaching Organisation, part of the College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine at University of Edinburgh. As her substantive post, Kirstin is Senior Academic Coordinator/MSc Year Lead in Clinical Education where she teaches on online distance learning programmes for those involved in undergraduate and postgraduate education across the health and veterinary professions. She is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. Kirstin is also a Senior Occupational Therapist in Urgent and Emergency Care with NHS Lothian. Kirstin is interested in the links between health and education, and how an understanding of occupation and occupational therapy can enrich teaching, learning and educational design, and support health though education. You can find Kirstin on Twitter (X) at @TherapyStatim↗️.