In this post, Dr Kirstin Stuart James introduces us to Jan-Feb’s Hot Topic theme: Through the Lens of Occupation. In this series, Kirstin offers a theoretical and situated reflection of perceiving our learning and teaching practices through the conceptual lens of ‘occupation’, drawing from her experiences as an academic and occupational therapist. In this first post, Kirstin sets the scene by unpacking the concept of occupation as the ‘thing’ people do that has implications in terms of embodied experience, agency, and wellbeing, among others.

In this six-blog series, I offer a different point of view regarding contemporary contexts of Higher Education (HE). My perspective has developed over decades of experience inhabiting multivariate professional roles across academia and occupational therapy. This affords opportunities to consider embedded theoretical discourses of health and wellbeing between practice areas, bringing with it the potential for fresh perspectives.

Starting with a pedagogical framework for occupation, the blogs that follow offer a different way to make sense of emerging and established academic practices through the lens of occupation. These include wellbeing and the occupations of teaching and learning, and the potential impacts of ‘artificial’ technologies and sustainability. The series closes with a future vision for health and wellbeing in HE. The upcoming companion podcast gives an overview of the series.

To first set the scene, it is important to unpack the ‘occupation’ in occupational therapy. Practically, occupational therapy is an Allied Health Profession. Put very simply, occupational therapists support people to do the ‘things’ they need, want, or have to do, across time, and across the lifespan (Royal College of Occupational Therapists, 2023). But within this simple definition lie layers of complexity (James, 2014).

The ‘things’ people do are their ‘occupations’, embodied as the activities undertaken to, for example, self-care, care for others, teach and learn, work, volunteer, earn a living, or fulfill our leisure interests. A complex relationship then exists between occupations, health, well-being, identity, and agency (Hocking and Wright-St. Clair, 2011). As succinctly put by psychotherapist Linda Finlay, “we are what we do” (Finlay, 2004, p.10).

However, pre-dating the 100-plus year history of professional occupational therapy (Wilcock, 2006) humans have long been ‘occupational-beings’. Earliest rock art depicts people supporting health through, for example, fishing and communing or as shown in Figure 1, by the very act of creating. Classical narrators spoke of occupations as the means to overcome the seemingly never-ending threats to health arising from the world around them (Wilcock, 2001). Further examples in ancient art show people engaged in multiple occupations. The Greek pottery in Figure 2, for example, shows images of the occupations of hunting-and perhaps trading-and animal companionship.

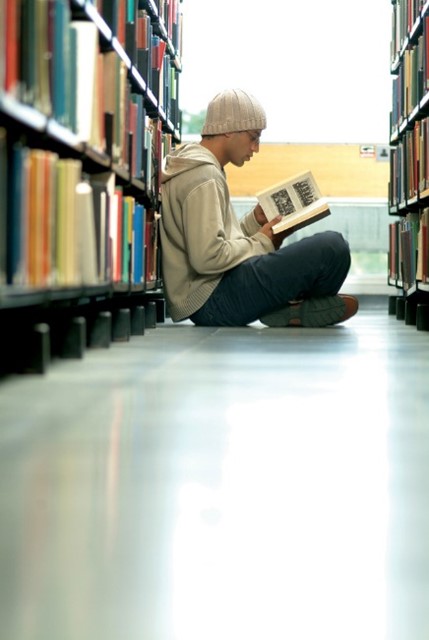

As such, humans have an innate need to ‘do’. By our ‘doing’ we have agency and can actualise. The ‘doing’ affords not only to ways to be and become but has value in and of itself. According to Nakamura and Csikszentmihaly (2009, p.195), the “complete absorption” in meaningful occupation, such as the occupation of reading shown in Figure 3, is a way to achieve the positive and health-supporting psychological state of flow. Theoretical concepts of the value of occupation to people therefore go beyond its therapeutic application in occupational therapy.

That said, this way of considering what it means to be human is not without critique. Historically, occupation-focussed theoretical frameworks tended to privilege the ableist constructs of ‘productivity’ and ‘independence’ and brought with them a doctrine that disregarded the importance of communities, culture, and spirituality to people, and at the same time did not take on-board the potential for negative impacts arising from human occupations (Twinley, 2013; Hammell, 2011; Hammell, 2009). Even the word ‘occupation’ can be detrimental when applied without sensitivity to context (Simaan in Ivlev (Ed), 2023).

Just, rights-based, contemporary theoretical frameworks have done more to conceptualise peoples’ occupations as part of a more complex theory of occupation, appreciating the person not as isolated from, but fully part of the world around them (Rudman, 2021; Hammell, 2017). This affords a greater emphasis on peoples’ participatory rights to occupation, alongside comprehension of the negative, human impacts on conflict, sustainability, and the environment.

It is such a contemporary theoretical context that informs the pedagogical translation of occupation put forward in the blogs that follow. By centring the embodied and situated occupations associated with teaching and learning within the broadest of human experiences, it may be possible to take a fresh perspective to what it means to teach and learn in contemporary HE and the relationship to human health. Writing from my personal perspective means teaching will tend to be referenced more than learning, but learning experiences can equally be considered through the lens of occupation.

References

Anon (n.d.) Aboriginal art in the Walga Rock cave.

Eklund, M., Orban, K., Argentzell, E., Bejerholm, U., Tjörnstrand, C., Erlandsson, L.K. and Håkansson, C. (2017). The linkage between patterns of daily occupations and occupational balance: Applications within occupational science and occupational therapy practice. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy, 24(1), pp.41-56.

Finlay, L. (2004). The Practice of Psychosocial Occupational Therapy. Cheltenham, Nelson Thornes Limited. Third Edition.

Hammell, K. R. W. (2017) Critical reflections on occupational justice: Toward a rights-based approach to occupational opportunities: Réflexions critiques sur la justice occupationnelle : vers une approche des possibilités occupationnelles fondée sur les droits. Canadian journal of occupational therapy (1939). [Online] 84 (1), 47–57.

Hammell, K. W. (2011) Resisting Theoretical Imperialism in the Disciplines of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy. The British journal of occupational therapy. [Online] 74 (1), 27–33.

Hammell, K. W. (2009) Sacred texts: A sceptical exploration of the assumptions underpinning theories of occupation. Canadian journal of occupational therapy (1939). [Online] 76 (1), 6–13.

Hocking, C. and Clair, V.W.S., 2011. Occupational science: Adding value to occupational therapy. New Zealand journal of occupational therapy, 58(1), pp.29-35.

James, K. (2014). The lived experience of occupational therapists in Scottish Accident and Emergency Departments. (Thesis). Glasgow Caledonian University.

Nakamura, J. and Csikszentmihalyi, M., 2009. Flow theory and research. Handbook of positive psychology, 195, p.206.

Royal College of Occupational Therapists, 2023. About occupational therapy. Available from: https://www.rcot.co.uk/about-occupational-therapy/what-is-occupational-therapy [Accessed 10 November 2023].

Rudman, D.L., 2021. Mobilizing Occupation for social transformation: Radical resistance, disruption, and re-onfiguration: Mobiliser l’occupation pour une transformation sociale: résistance radicale, perturbation et reconfiguration. Canadian journal of occupational therapy, 88(2), pp.96-107.

Ivlev, S.R., 2023. Occupational Therapy Disruptors: What Global OT Practice Can Teach Us About Innovation, Culture, and Community. London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Twinley, R., 2013. The dark side of occupation: A concept for consideration. Australian occupational therapy journal, 60(4), pp.301-303.

Wilcock, A.A., 2006. An Occupational Perspective of Health. Slack Incorporated.

Wilcock, A.A., 2001. Occupation for Health: A Journey from Self Health to Prescription: v. 1. London, College of Occupational Therapists.

Kirstin Stuart James

Kirstin Stuart James

Dr Kirstin Stuart James is currently on secondment as Deputy Programme Director within the Clinical Sciences Teaching Organisation, part of the College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine at University of Edinburgh. As her substantive post, Kirstin is Senior Academic Coordinator/MSc Year Lead in Clinical Education where she teaches on online distance learning programmes for those involved in undergraduate and postgraduate education across the health and veterinary professions. She is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. Kirstin is also a Senior Occupational Therapist in Urgent and Emergency Care with NHS Lothian. Kirstin is interested in the links between health and education, and how an understanding of occupation and occupational therapy can enrich teaching, learning and educational design, and support health though education. You can find Kirstin on Twitter (X) at @TherapyStatim