In this post, Rayya Ghul at the Institute for Academic Development dives into the literature to break down the (sometimes elusive) reflective process into teachable ‘orientations’. Rayya explores how approaching reflection in this way, as a matter of style(s), can better integrate reflection into disciplines and industries such as healthcare and beyond. This post is part of the Learning & Teaching Enhancement Series: Reflective Learning.

I began my academic career teaching occupational therapy in 2000. In common with most professional degrees, especially in Health and Social Care, there was a requirement for students to engage in ‘reflection’. I am sure other contributors to this blog series will also state that a) it is notoriously difficult to define, let alone teach reflection, and b) that students by and large hate being asked to reflect.

The most common approach to teaching reflection in Health and Social Care is through the use of models, such as Gibbs’ cycle of reflection, which take a staged approach, usually accompanied by questions that broadly fit a pattern of ‘what, so what, and what next?’. Some models ask students to consider their feelings first (how did it make me feel?), while others focus on actions (what did I do?) or events (what happened?). Although these cycles do encourage richer sources of reflection such as feelings and technical knowledge, they are essentially a closed loop, limited by what you do (or don’t) know already. For occupational therapy (and, I suspect, other similar professional groups), this was not really satisfactory because the purpose of reflection is not solely about consolidating learning, but also about developing, enhancing, and securing professional practice.

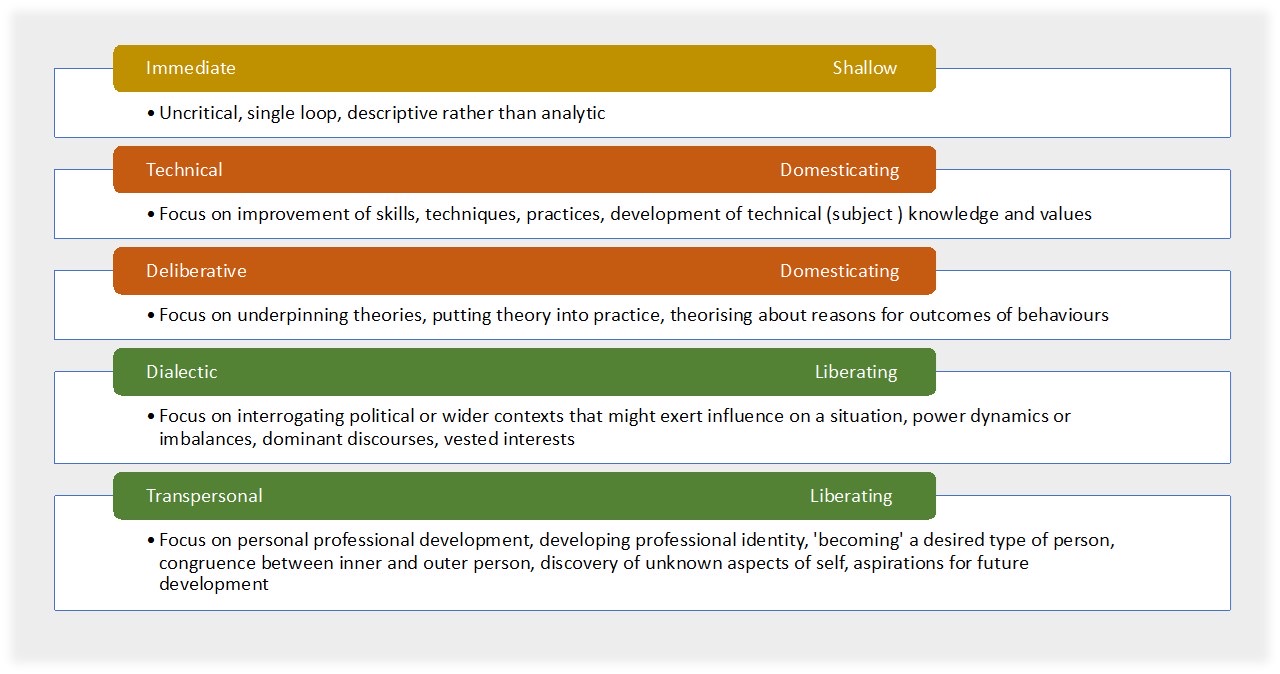

I began to look for better ways to teach reflection and came across an article called ‘Orientations to Reflection’ (Wellington and Austin, 1996), which contained an analysis of reflective journals of student teachers. Each style or focus of reflection was themed into five orientations: immediate, technical, deliberative, dialectic, and transpersonal, and the latter four then split into two purposes: domesticating and liberating (see Figure 1). I liked the idea of an ‘orientation’ as it opened the possibility of changing orientation or adopting a different orientation. The differing purposes (of reflection) provide a rationale for choosing different orientations and, more importantly, exclude descriptive, shallow writing as ‘not reflective’.

Another advantage of this framework is that it helps the student to understand the purpose of reflection. The ‘domesticating’ orientations are designed to integrate and embed the knowledge, skills, and values of a professional practitioner, while the ‘liberating’ ones develop critical thinking and professional identity. In particular, the ‘dialectic’ orientation is very good for helping students think about power imbalance and issues around equality and diversity. We know that all employers, not only in healthcare, value critical thinking as a key graduate skill, so these additional orientations are highly effective in preparing the student for questioning and articulating critical perspectives.

From this framework I developed a series of questions corresponding to each orientation that students could use to write about an incident, moving from one orientation to another. Having tried this approach out with undergraduate and Masters occupational therapy students, who almost unanimously said that they found it the most useful tool they’d been given, a colleague and I decided to develop an entire final-year module for the BSc Occupational Therapy called ‘The Reflective Practitioner’ and designed a series of activities to take students through the different orientations. Any lecturer from a course that requires critical reflection will be familiar with the resistance and dislike for reflective tasks that student generally demonstrate. We were therefore gratified to see that the course approval rating was consistently high with qualitative comments even suggesting they positively enjoyed reflection now.

The assessment for The Reflective Practitioner was based on a task running through the course. Students brought a reflection on a placement incident that they had written in the previous year as part of their coursework. After each course session, they were asked to update their reflection. By the end of the course, they had updated their reflection ten times. Rather than hand in the updated reflection, they were required to write an essay reflecting on the updating process and what that had taught them. One of the important reasons for teaching reflection to health professionals is that critical reflection on practice promotes enhancement and safety for the professional, the service, and the service user. The students’ essays demonstrated that this was clearly understood even by the academically weakest students.

The orientations framework is also very useful for creating assessment rubrics for evaluating reflection as they can be easily translated into statements describing what is expected to be seen in critical reflection. We also developed a detailed set of descriptors for each orientation to research whether there was evidence of improvement from the initial reflection to the final updated one. These were handed in as unmarked appendices and so a comparison could be made. We were able to demonstrate that all students had gained at least one more orientation, the majority had gained two, and a significant minority were confidently reflecting in all four orientations.

References

Wellington, B. & Austin, P. (1996) “Orientations to reflective practice”, Educational Research, 38:3, 307–316.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. London: Further Education Unit.

Postscript: Gibbs’ reflective cycle is by far the most popular in use by health professionals, cited in almost every textbook. As a good academic, I went to look for the original cited above. It was nowhere to be found on the library shelves (of my former HEI) and when I enquired at the desk I was informed I could have a copy for a 3-hour loan. I was intrigued – how could such a seminal text be so rare? It turned out to be an A4 paperback manual, designed for BTEC students in FE. I genuinely believe that I am one of the only people who has tried to find the original! Graham Gibbs (who is a brilliant HE educator) has himself said that he is puzzled that such a ‘coarse tool’ became so popular. It definitely was a forerunner of other texts on experiential learning, but I remain unconvinced that it produces genuinely rich reflection. For curious readers, here’s a link to a pdf of the original: https://thoughtsmostlyaboutlearning.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/learning-by-doing-graham-gibbs.pdf

Rayya Ghul

Rayya Ghul

Rayya is a National Teaching Fellow and lecturer in University Learning and Teaching. She is based in the Institute for Academic Development where she is the University Lead for the Edinburgh Teaching Award and convenes the course on Accessible and Inclusive Learning. Rayya runs Practical Strategies sessions on embedding access and inclusion into the curriculum and also ways to apply a solution focused approach to supporting students in a variety of roles.

[…] R. (2022) Using an “orientation to reflection” framework. Learning & Teaching Enhancement Series: Reflective […]