By Ray Honeysett

The history of astronomy in Asia is rich and valuable to astronomers to this day. Observations made in 11th century China are used as evidence for phenomena we can still see in the sky. There have been many ingenious minds that have made breakthroughs in science in Asia. Mathematicians like Aryabhata and Brahmagupta may be unfamiliar names, but their discoveries are as important as any other scientists to have lived.

Chinese Astronomy

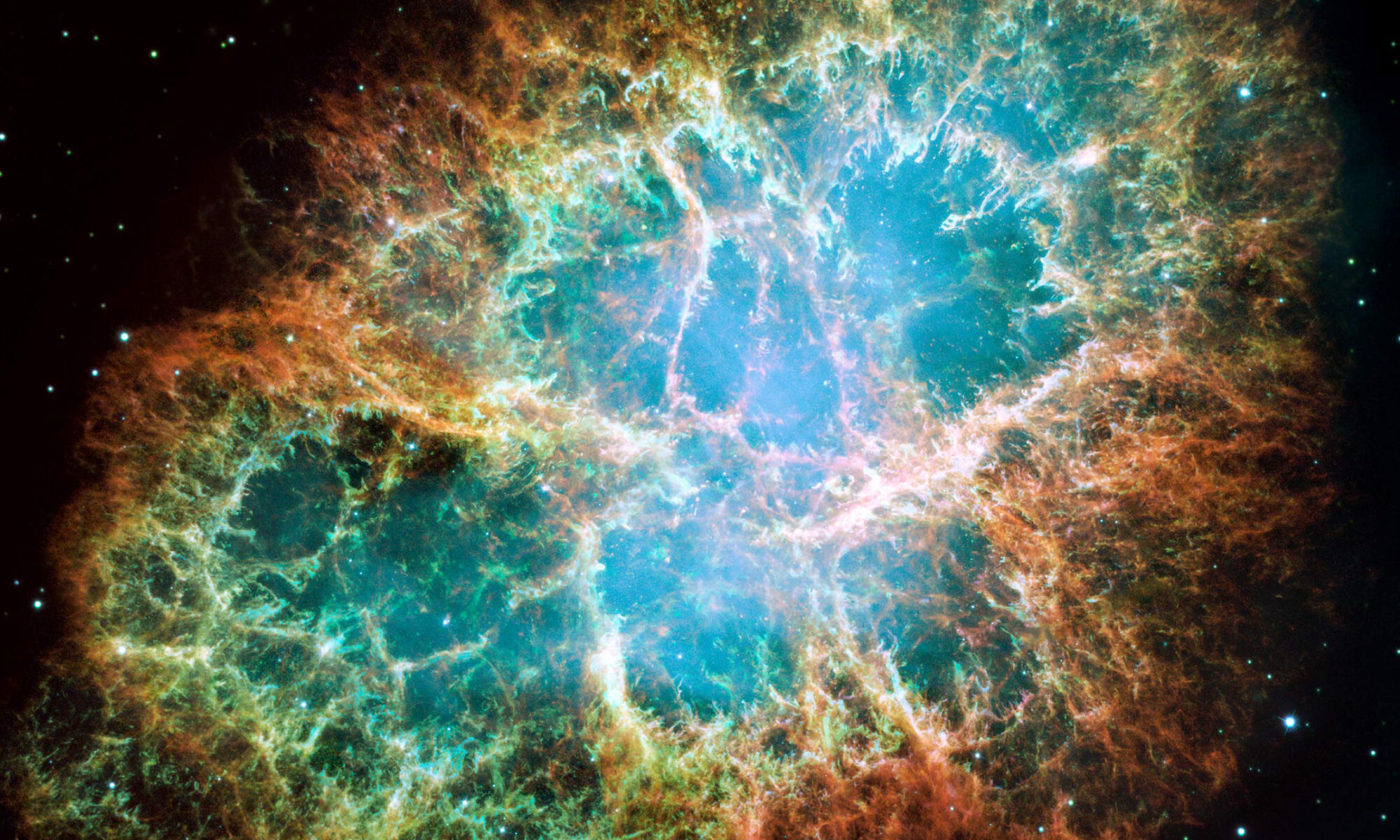

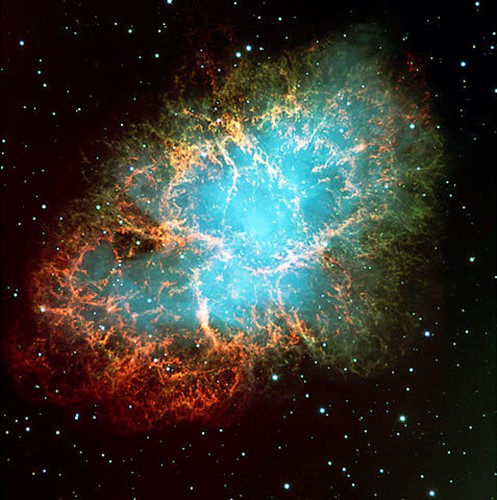

Evidence of Chinese astronomy dates back at least as far as 500 BCE, with Chinese observations being some of the most important observations made in the world to date. As early as the 11th century AD, Chinese astronomers recorded supernovae. They did not know what they were initially, but called them ‘guest stars’, noting that they were not constant, but appeared suddenly and slowly became more faint. It is thanks to the records made in 1054 AD in China in the paper Song Huiyao Jigao that we know first knew about the Crab Nebula, the result of one of the supernovae that were recorded.

Today, China continues to make progress in Astrophysics. The Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Radio Telescope (FAST) in Guizhou, China is the largest telescope of its kind in the world. During its testing phase alone, scientists used it to discover over 100 pulsars. These pulsars are a type of neutron star – the super-dense core of what used to be a massive star – that emit light in beams from their axis. Pulsars rotate at a regular speed, and this means that from Earth, they appear to rhythmically get brighter and darker as the pulsar beams point in the direction of our planet, and then rotate to face another direction. The emissions from pulsars are so regular, that it is thought that a disruption of their light could be a sign of gravitational waves. For this reason, there is huge interest in pulsars at the moment, as accurate readings from pulsars could lead to the detection of gravitational waves that are much smaller than the ones currently detected by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO).

The Crab Nebula supernova, has now resulted in the formation of the Crab Pulsar, one of the pulsars being investigated for signs of gravitational waves.

Indian Astronomy

Aryabhata, a prominent astronomer and mathematician in 5th century India, wrote papers in which he explained his understanding of astronomical objects. He understood that the spinning of the Earth caused day and night, and he saw that the moon and planets were not sources of their own light, but rather reflected the light of the Sun. Knowing that planets reflected light made people start to theorise about what the planets were made of, and how this differed to the make up of the stars.

Also incorporated into Aryabhata’s theories was the idea of a heliocentric solar system, a great insight on the part of Aryabhata to let go of the impulse of thinking of Earth as the centre of everything. The legacy of Aryabhata is found in all following physics – in the 13th century, his work was translated into Latin and lead to the development of science in Europe.

Following on from his work, the mathematician Brahmagupta in the 6th century gave his own take on the movement of the planets. By looking at the orbits of the planets, he realised that they must be held in their motion by a force towards the Sun. He believed that this same force was what caused things to fall to Earth, and, of course, he was right; the force was gravity.

Today, India is a stakeholder in many significant observatories and projects, such as the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) in South Africa and Australia, which will be used to observe a huge range of light sources with much more sensitivity than was previously possible. There are plans to create machinery capable of detecting gravitational waves, in a project known as IndIGO (Indian Interferometry Gravitational-Wave Observatory).

Malaysian Astronomy

Malaysia encompasses a wide range of cultures, and historically, astronomy has been very important there. The first use made of astronomy was farming; rice has long been an important dietary stable, and astronomy could be used to tell the time of year that it would be best to sow the rice.

A group of the Dayak people both in Malaysia and Indonesia, had a particular unusual and ingenious way of finding the right time to plant rice. They would fill up a length of bamboo with water, and, at night, this stick of bamboo would be pointed towards a guide star. Some of the water would spill out of the end of the bamboo, and if this amount of water was correct, then it was the right time of the year to begin farming.

Another use of astronomy was for celestial navigation, which was invaluable in travelling across Malaysia’s hundreds of islands.

Malaysian astronomy continues to expand, and 2019 saw the formation of the Malaysian Space Agency (MYSA). So far, MYSA have worked in collaboration on an international scale to observe radio readings from the Sun 24 hours a day. They also support the Langkawi National Observatory (LNO), an optical observatory on an island in the north-west of Malaysia.

Sources

Ammarell G. (2008) Astronomy in the Indo‐Malay Archipelago. In: Selin H. (eds) Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer, Dordrecht

Cofield, C., 2016. What Are Pulsars?. [online] Space.com. Available at: <https://www.space.com/32661-pulsars.html> [Accessed 16 June 2020].

Long, T., 2012. July 4, 1054: Crab Nebula Makes A Spectacular Debut In The Heavens. [online] WIRED. Available at: <https://www.wired.com/2012/07/july-4-1054-crab-nebula-makes-a-spectacular-debut-in-the-heavens/> [Accessed 16 June 2020].

McPeak, William J. “Physical Science in India.” Science and Its Times, edited by Neil Schlager and Josh Lauer, vol. 1: 2,000 B.C. to A.D. 699, Gale, 2001, pp. 245-248. Gale eBooks,

Mysa.gov.my. 2020. Astronomy. [online] Available at: <http://www.mysa.gov.my/portal/index.php/research-and-development/space-science/astronomy> [Accessed 1 July 2020].

Pingree, D., 2014. Indian astronomy. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 104(3), pp.205–208.

Powell, J., 2019. From Cave Art to Hubble, Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Srianand, R., 2019. Indian astronomy in the next decade. Current Science, 117(6), pp.907-908.

About this article

This article is part of a series exploring astronomical research from around the world. To find articles about other continents, check the ‘Under the Same Sky‘ tag.

This article was written by Ray Honeysett as part of her student internship role with the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Committee at the School of Physics and Astronomy. This role was part of the Careers Service Employ.ed on Campus scheme.

Ray is currently studying for a MPhys in Astrophysics.

(ESO via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.)