I was on the annual geophysics field course last week, so, as promised, here is what happened.

This year, we were in the White Peak, the part of the Peak District near Tideswell, Derbyshire, and as in previous years, with staff and students from the universities of Münster and Paris Sud. The students were divided into five teams, with each team choosing a field and applying a different geophysical technique to their field every day. I went to each field in turn to supervise gravity measurements.

Monday and Wednesday’s fields were in the village of Peak Forest. Monday’s field had very dull gravity; the most interesting thing to happen all day was meteorological. The weather was unseasonably pleasant all week, but on Monday there was the additional excitement of a splendid halo display.

This has two clear parhelia (the bright spots either side of the Sun), a good fraction of the 22° halo (the faint rainbow circle joining the parhelia), a bit of the parhelic circle extending outwards from the parhelia and a hint of an upper tangent arc at the top of the 22° halo. (There is more information about these halos on this page of the splendid atmospheric optics web site.) There was also (but not at the same time) the longest and brightest circumzenital arc that I have ever seen:

The sky was definitely smiling at us!

Wednesday’s field was on the side of a little hill, with one of the lines of data going nearly to the top of the hill. The main lesson we learned from that was the importance of doing your terrain corrections if you are going to do a gravity survey that goes to the top of a hill. We also learned to be wary of cows.

This particular herd had acquired a bit of a reputation earlier in the week by eating a section of a 100m tape measure belonging to a German professor. He was not best pleased. Fortunately, they left us and the gravity equipment alone.

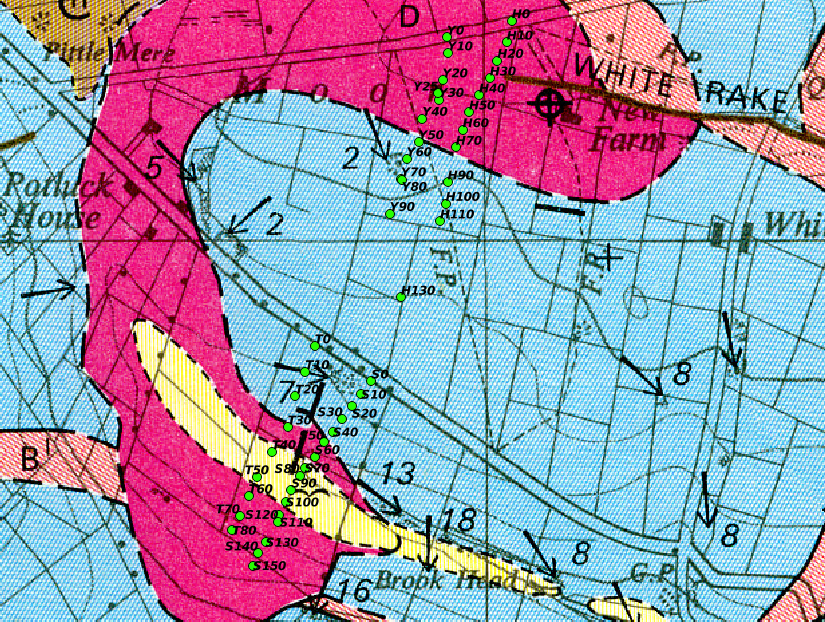

Sunday, Tuesday and Thursday’s fields were adjacent to each other and, as it turned out, the gravity was a bit more interesting. Here are our data points (green dots), on top of the BGS’s geological map (1:25000 special sheet “Miller’s Dale”); the colour scheme is blue=limestone, red=dolerite, pink=basalt and yellow=recent alluvial deposits.

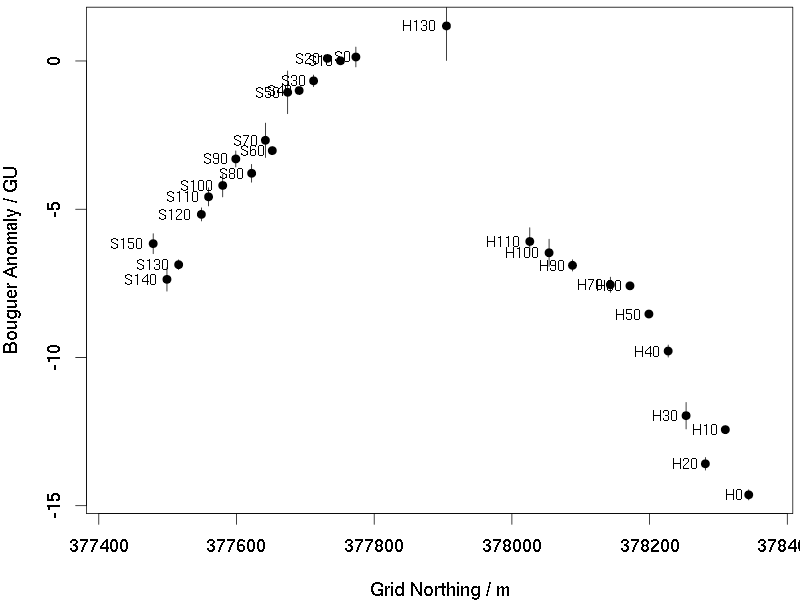

The S points are Sunday (continued Tuesday), the T points are an extra line done on Tuesday and the H and Y points are from Thursday. I didn’t realise how close Thursday’s field was to the other patch until the mid-morning mist cleared away and I could see across to some of our vehicles parked near point S0. I don’t think the students were very pleased when I got them to hike across an extra field to get data point H130 and tie the Thursday data into the other days by re-measuring at S0. It was worth doing, though.

The S points are Sunday (continued Tuesday), the T points are an extra line done on Tuesday and the H and Y points are from Thursday. I didn’t realise how close Thursday’s field was to the other patch until the mid-morning mist cleared away and I could see across to some of our vehicles parked near point S0. I don’t think the students were very pleased when I got them to hike across an extra field to get data point H130 and tie the Thursday data into the other days by re-measuring at S0. It was worth doing, though.

Both gravity meters that measured this set of points agree that there is a maximum in gravity at H130, and that the values decrease as you go North or South from this point. I’m not totally convinced that the two halves are properly tied together; the jump between H130 and H110 looks very sharp. The two gravity meters agree, but there may be a surveying error; the group measuring the heights of each station found that part of the surveying quite difficult due to the stone walls and the road. But a 6GU gravity error is equivalent to a 3m surveying error, and that sounds far too large.

A reasonable hypothesis is that the positive gravity anomaly is due to the dolerite; this supposedly forms a big horizontal slab or sill which is exposed at the surface in places and underneath a layer of limestone in others. Just as in Germany two years ago, having found an anomaly, it turns out that our data do not cover a large enough area for us to model it convincingly. If we go back to the Peak District in 3 years time I hope to extend the line of measurements a considerable distance North and South of the region we covered this time.

Interestingly, although there is dolerite and basalt spread all over this part of the geological map, the casual visitor to the area could be forgiven for thinking that the only rock present was limestone. There are many places where the limestone is visible, but everywhere that dolerite is marked on the map, one just finds grassy fields on the ground. If you look carefully, a few of the stones in the drystone walls are a dark igneous rock which I assume to be the dolerite. One tends to think of igneous rocks as being more resistant to weathering than sedimentary ones, but here the reverse seems to be the case. I have never seen an exposure of the dolerite sill. On the last day, however, on a walk along the Wye valley to the pub at Miller’s Dale I found an exposure of lava just next to the road:

No doubt that it is lava: it is dark, hard and very fine-textured apart from the huge bubbles — almost entirely unlike limestone. The geological map assures me that this is called the Lower Miller’s Dale Lava.

Next year: Back to the Vogelsberg!

7 Replies to “Cows, Halos, Gravity”