The ALT 2025 conference: AI, disaster cycles, and conscientious objectors

On the 23rd and 24th of October a few of us attended the Association for Learning Technology’s 2025 conference at the Marriot hotel in Glasgow. The Educational Design and Engagement team had a couple of presentations in the parallel sessions, with Paul and Robyn presenting on the excellent work that our Learn Foundations students do, and Fiona, Nikki and myself presenting on our new Short Courses Platform.

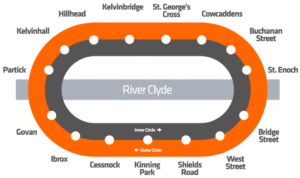

Map of the Glasgow Subway

For our presentation on the short courses platform, we literally had the graveyard slot at 4:15pm on Friday, but a few dedicated souls came along came along seemed engaged with our work. We used cartography and the Glasgow underground map as metaphors for the work we’re doing to help make lifelong learning journeys easier – we discussed the discovery, user experience research, and user centred design work we did to surface the hidden mass of non-traditional courses that are available from across the University of Edinburgh. Have a look at our slides to get a feel for how we approached this. Have a look at our slides to get a feel for how we approached this.

Charles Knight, director of leadership, governance and management at Advance HE, gave the opening keynote on day one. He used the opportunity to reflect on AI as an opportunity to think about the need for us to develop the human leadership that technology-rich futures will require. In a world where AI is increasingly positioned as the solution for everything (and the problem), what are the uniquely human skills that are indispensable? The answer, of course, is that human skills are central to everything and key among them he positions leadership, data literacy, and emotional intelligence.

I think my biggest insights came from the two AI workshops that I attended (AI was inescapable at this conference). The first discussed AI in the context of disaster cycles, a four-phase model first proposed by David Alexander in 2002, including mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. The suggestion here is that, as learning technologists, we did not learn from the COVID pandemic: if we consider the digital pivot as a disaster, then we didn’t prepare for another ‘black swan’ event, such as the impact of genAI on digital education. This framing allowed us to break out into four groups to discuss the genAI ‘disaster’ within these four phases. Generally, I quite liked the idea as a discussion starter, but hoped that nobody really thought genAI is a disaster event. The discussions seemed to focus around the need for policy and/or whether the process of policy making was responsive enough, and also the need for training and modelling of practice. These themes resonated with other discussions I’ve heard. It made me reflect that my position on AI leans more towards thinking about it as the coming together of a bunch of things that were already happening and less a sudden and disastrous event. I don’t really feel the panic.

The second workshop was led by colleagues from the Scottish AI in Tertiary Education (ScAITEN) group. As an institutional representative on this group I am familiar with their work. They have developed a grass roots position paper and are now attempting to take this to Scottish government (it very much follows the approach of Open Scotland). As part of the workshop, we were set some provocations to discuss and the one I chose to take part in was how to deal with AI conscientious objectors – what to do if students or teachers decide to purposefully opt-out of using AI. Now, this drew a lot of debate around the table. Someone who works for an EdTech company claimed this would be like opting out of using the internet in the late 90s. Another attendee said that their university had amended lecture recording policy because they were concerned about captioning being a form of AI and the risk to academic IPR (i.e. the policy was opting out of certain forms of AI). I think what this told me is that we really don’t all mean the same thing when we talk about AI – therefore the context of practice is really key. We ended up drilling down to a sort of philosophical question that I think gets to the heart of this discussion: if two students are doing the same assignment and one opts to use genAI and the other opts not to, which one is disadvantaged? For my money, the one who uses genAI is more at risk of being disadvantaged because learning is a process that can’t be speeded up by technology – it’s slow, sometimes painful, but ultimately changes the very core of what you are. That sort of ‘cognitive offloading’ just doesn’t feel as enriching to the soul. I hope we might eventually realise that students don’t want to offload their learning to genAI at all (because it doesn’t feel good) – and AI is not the disaster for education we thought it was.

(By SPT - http://www.spt.co.uk/subway/, Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51958499)