Investigating Hybrid Teaching & Learning Worldwide

A couple of months ago, a project landed on my desk (virtually, in my sitting room, where I’ve been for 15 months) involving an investigation of current hybrid teaching and learning practice. The task was straightforward enough: find out what kind of hybrid synchronous systems are in place in other institutions worldwide.

So, I spent about three weeks searching fairly intensively for the hybrid teaching and learning offerings at other universities – this includes any and all universities, across the globe, from those at the top of various rankings charts, to those less well-known institutions who have incredibly precise and detailed HyFlex classroom charts and guidance.

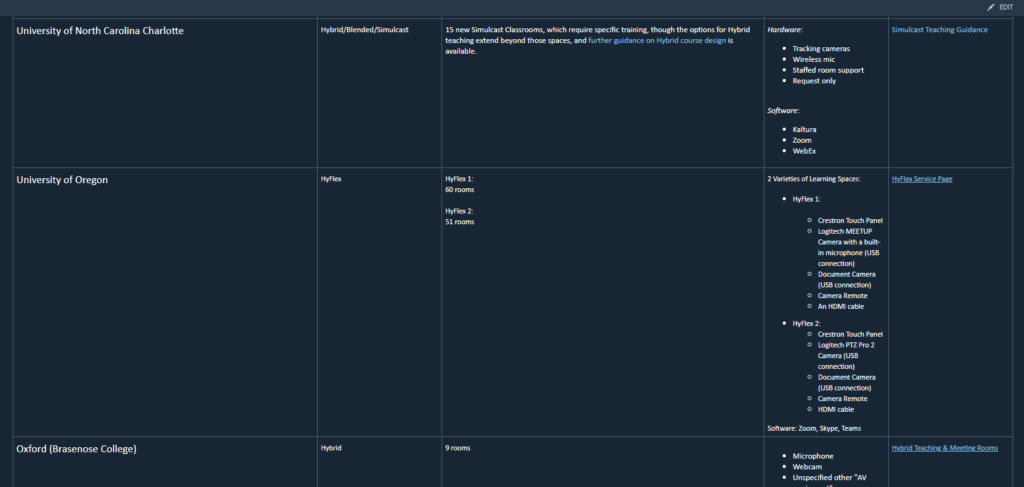

Methodologically, the process was more or less straightforward – lots of googling. I entered every possible combination and variation of the words “hybrid” “hyflex” “teaching” “university” “college” and so on, and read quite a lot of articles from every corner of the internet. For each institution I investigated, I made notes in a wiki-style table on a SharePoint page with a view to eventually open my findings up for further discussion. The table became a bit unruly and took on a life of its own, but it was a very good starting point for evaluating the consequences of hybridity, as it were, over the last year.

Compiling a table of other institutions’ practice allowed me both to take a step back to do some light analysis of where we’re all at as a global educational community, and to zoom in (sorry) where necessary for very specific information such as individual room layouts. I found this project incredibly useful, as one side effect of the past year has been, understandably, a feeling of institutional isolation, and uniting so much excellent work in one space, even on my own, gave me a sense of opening avenues up instead of closing them down.

A snapshot of how the Hybrid Teaching and Learning table works

Newly able to identify some patterns across built teaching spaces, I also found links in various pedagogical approaches, and in certain administrative matters as well. As briefly as possible, the most commonly reported complications or challenges across all institutions were the following:

- Audio feedback with students using personal mics/headphones

- Equity of access to highly specialised equipment

- Pressure on staff to provide extra support

These topics aren’t ones that have easy answers, and they will be the subject of ongoing conversations in coming months and probably years. However, a lot of solutions have been put into place to address other challenges. For example, many institutions have created thorough guides for multiple modes of teaching, and are allowing each department, or even each instructor to decide which mode will work best for their subject and students.

The latter approach highlights an obvious, but often-forgotten point: the university is not a monolith, the students and others in our community all have varying needs, strengths, and worries. Nuance and flexibility in course delivery allows each teacher, learner, or professional practitioner to make decisions they feel are right for them and those they’re working with, within a range of options supported centrally to ensure fairness and transparency.

Thinking forward to 2022 and beyond, my hope is that work like the table of practice I’ve put together might help us prioritise the people in our community in new ways. The technical tools allowing us to implement innovative modes of teaching and learning are just that – tools. It’s up to us to figure out how to put them to use to foster connection, curiosity, and a sense of belonging in our shifting hybrid landscape.