Mary Holmes

Looping out from the flat and back to the flat, my walks got longer. Isolated walks, without isolation. This was walking under strict lockdown and it hasn’t changed much yet, except you can stop. You can sit down for as long as you like. If there is sun, you can sit on the grass and read and drink coffee. This is exciting and having other people near, but not too near, is starting to feel okay. Before It was a challenge to find nice places to walk that were not too crowded. The canal was no good, unless the weather was bad. Other wise the tow path made it hard to stay 2 metres apart when passing. The best place for walking was the richer neighbourhoods nearby. People with big gardens and big houses didn’t need to be out, so the leafy streets were a good place to wander and to see spring blossoms and smell grass and trees. You could also eye up the property. Dreams are free.

Lockdown walking means not really going anywhere. That is different to going somewhere for something. Like Ashley Barnwell, I used to walk to get somewhere, to go to work, to buy something. Now ‘I walk to walk’. There is an extravagance in that, but also a parsimony. What else can you do?

At first it was difficult to be polite and avoid people at the same time. Someone thanked me for thanking them when they stood back to let me pass where the pavement narrowed. These are new social courtesies, and new interaction rituals; uncertain, a little complicated, slightly too much. Between encounters, when you are walking just to walk you can think, so I thought about walking. What would a Sociology of walking look like?

Walking has a history. For sociologists that might start with an appreciation of how industrialisation and urbanisation changed why, where and how people walked. For many ordinary new city dwellers, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, it seems likely that walking long distances to market was replaced by walking shorter distances to work. City walking had its people watching pleasures, as early sociologists like Georg Simmel and Walter Benjamin noted. However, as more and more people lived in urban areas, walking often became a leisure activity done in the countryside. Rambling clubs became popular from the 1930s in Britain. Later, as urbanisation turned into suburbanisation, suburbanites walked very little, getting into their cars to drive to suburban malls, where they walked to shop. As the ubiquity of cars has increased, pedestrians have been sidelined and spend more of their time watching out for cars than looking at the world around them. And yet walking is recommended as a fitness activity, good for our health and wellbeing.

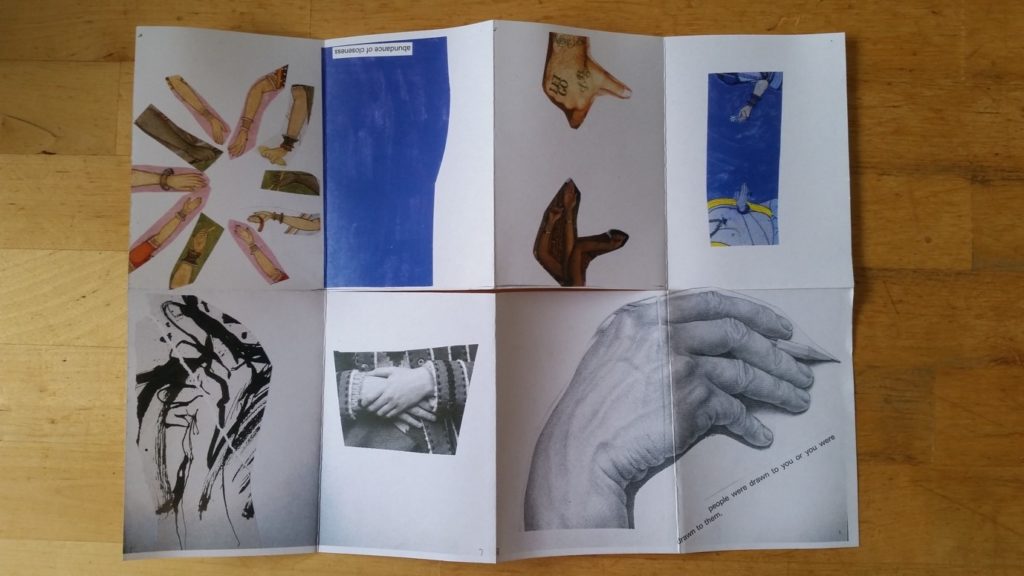

Different kinds of people walk differently and we can compare. Women and men have different ways of walking, imbibed through socialisation and years of practice. Men are more likely to stride out, and women to be more contained, to take up less space. At least, that is what we might imagine if we extend Iris Young’s ideas about throwing like a girl. How we walk is also shaped by human technologies like high heels or fancy trainers or those weird toe shoes. Not everyone can afford good shoes, and various medical studies show that improper footwear can lead to back or foot problems. How much money you have also means that if we compare working class to middle class people, their options for walking will differ. Middle class people are more likely to be able to afford to access the countryside or live near parks, while those in deprived areas might be reluctant to walk around their neighbourhoods, especially if gangs are present or even just because there is a lack of green spaces nearby.

These comparisons help in thinking critically about walking, they help to consider what kinds of inequalities are attached to it. Women may not feel safe walking about the city, especially at night, constrained by fears of violence. In other places, some women may be constrained by cultural practices that do not allow them to walk out in the world without a male relative to accompany them. Other women may walk too much, covering large distances daily to collect water or firewood. And to think critically about walking means thinking about those who cannot walk easily or at all due to a physical impairment. How are they disabled by the way in which society is organised and cities built? Think about the cobbles and curbs that can’t be navigated by wheelchair or the step-free routes that are too long for older people with limited mobility. And what about African Americans for whom a stroll to watch birds in the park can lead to racist abuse, or a walk to buy cigarettes can end in being arrested and killed by police? Power relations and structural issues like racism and sexism affect who walks where and with what consequences.

From injustice, resistance and change can come. Despite the still high levels of Coronavirus in the US, hundreds of thousands of people have been out on the streets marching together to protest over the killing of George Floyd. There is a history of freedom marches to fight against racism and walking with others has long been a form of protest against all kinds of injustice. I remember this when my daily walks feel like they are going nowhere.

Sources and further reading

Conley, J. (2012) ‘A sociology of traffic: driving, cycling, walking’ pp 219-236 in Vannini, P. (ed). Technologies of Mobility in the Americas. Oxford and Bern: Peter Lang.

Freund, P. and Martin, G. (2004) ‘Walking and motoring: fitness and the social organisation of movement’ Sociology of Health & Illness 26(3): 273-286.

Harries, T. and Rettie, R. (2016) ‘Walking as a social practice: dispersed walking and the organisation of everyday practices’ Sociology of Health & Illness, 38(6): 874-883.