Very good discussion with Aphaluck Bhatiasevi from the excellent Covid-19 Perspectives blog, also Edinburgh based.

Very good discussion with Aphaluck Bhatiasevi from the excellent Covid-19 Perspectives blog, also Edinburgh based.

Liz Stanley

What’s happening to sociological imaginations in present circumstances? Having been to lots of other university sociology websites recently, the dominant trend appears to be that sociology folk have fallen into research mode, and research mode of a fairly standard kind. Nothing wrong in that, of course, and in a sense it is what sociology is for. At least there is a response to present circumstances. But it is interesting that there is little highlighting or consideration in any depth of the kind of things friends, colleagues and I have been communicating about over the last few weeks. What is happening is not standard, so sociological responses should hopefully become far wider. Brainstorming on this, and rereading emails and thinking about conversations in Skype, Zoom and Teams meetings, the kinds of things that have come up in discussions I’ve been party to include, for starters:

What are other sociologically-minded people feeling, thinking, talking about? Contributions on any of these or other aspects are welcomed and can be as brief as you like and take the form of a paragraph, short essay, photograph, poem…

Poppy Gerrard-Abbott

Poppy Gerrard-Abbott is a PhD researcher at the University of Edinburgh looking at sexual violence in universities. She is also a sociology tutor, feminist activist and has just started a sociological podcast on the COVID-19 pandemic, Difficult Conversations. She works as the lead researcher for the Emily Test charity creating a Gender-Based Violence Charter for Scottish Universities and Colleges and she often runs women’s circles focusing on gender-based violence.

@GerrardPoppy

Respond to this blog: pgerrard@ed.ac.uk

What has happened to us all? Coronavirus is a health issue, yes, but there’s something about such a crisis that brings out the pessimist, the optimist, the conspiracy theorist, the journalist, the judge, the social media influencer, the feminist, the radical revolutionary – even the yoga pro, pastry chef and the wannabe broadcaster in us. It can also bring out the resentful, the angry, the fearful and the blamer in us. It brings out the doomsday in us. Can we break free from ‘it’s the Chinese trying to take over the world’ / plague sent by God / the end is nigh? Yes, I believe we can, and as social scientists, I think sometimes we are sometimes well-positioned to help cut through looming, dark dystopia. Such sentiments are also telling us something – people have a lot to say right now, and we perhaps have a responsibility to hear and record it.

In March, I recorded a podcast with my colleague and friend, PhD researcher on digital intimacy and sex work, Eva Duncanson, because we were due to deliver two lectures together. These were cancelled due to the sudden outbreak and then came a lightbulb moment (that I wish had occurred much earlier on in my PhD so I could spend less time stressing and more time writing the damn thing): in a crisis, I don’t have to produce things that are perfect. Wow – who knew? It took a pandemic for me to realise that under stress and change, something is better than nothing. So in 48 hours, we mashed the lectures together into a podcast, decided to put it up on Youtube, spent a couple of hours swearing and then it was uploaded.

When the Edinburgh Decameron website was about to be published, I was asked: ‘How did you come to have the idea for the podcasts and how did you make the podcast happen?’ Well, with my newfound attitude of ‘imperfection is always better than nothing’ (I am hellbent on making this last) the Difficult Conversations podcast was born following on from my podcast with Eva. Firstly, I enjoyed it so much that I thought ‘why end it here?’. Secondly, when the pandemic broke out, I had moments where I felt like nothing else really mattered in social science research except crisis: climate change, why Trump is Trump, and COVID-19. I pondered about submitting an ethics application to do some formal research on sociological approaches to COVID-19 but I knew there would be others better resourced than a self-funded PhD student like me working two to three jobs at any one time. Plus, with such a workload, I didn’t want to chain myself to writing a coronavirus thesis on top of my PhD and the other research work I do. I didn’t want the isolation of writing, the head-spinning document corrections, the slowness of writing a paper. I craved for something that brought people together, got us talking, let off steam from the crisis, allowed for both laughing and seriousness, and got content out fast.

This approach was hugely complemented by the ‘it’s either imperfect and finished or perfect and unfinished’ attitude I learnt early on in the pandemic when I just couldn’t find the right online birthday gifts for friends and family and I never got further than item one on my to-do list because my workload increased so much from the pandemic (teaching, working in gender-based violence, looking after people). At first, I was worried that I couldn’t release anything until I had a professional microphone, 25 audio editing tutorials under my belt, and a graphics qualification. I then remembered that we were in the middle of an unprecedented pandemic, with limited stocks, slow deliveries, fast-moving policy, people at risk and people literally dying. I put the perfectionism down and decided that a rough-around-the-edges approach was exactly what I needed to re-learn and what the world needed to expect at these times.

It’s punk rock academia, that’s what I’m convincing myself: me, three days in the same leggings, my dipping Wifi connection, my cereal-bowl covered desk and my laptop. We’re going to create a podcast series together. That’s right. In the words of my next door neighbour “Well, pirate radio changed the world”. Yes, I thought. Pirate radio station operators weren’t concerned with capitalist productivity and shiny studios.

Completing this picture is an Argos microphone – which, by the way, was one of the few brands not out of stock. I am currently imagining how many Dads have bagged such microphones and are currently in their garages living their dreams and ticking through the pandemic by DJ-ing their favourite 60’s playlist to three listeners. It fills my heart with joy.

I kept my philosophy in sight: forget perfection, just produce content that matters. Record what’s going on, and get people talking. During this pandemic, I learnt that I’ve had a gendered and subconscious belief for years that I just cannot understand technology. I don’t like it and it doesn’t like me. It was a load of rubbish – everyone, absolutely everyone, is always in process.

Since it began the podcast series has covered sex work, feminist approaches to COVID-19, single mums, the higher education strikes, supermarket workers, and pandemic financial difficulty. I recruit guests through colleagues, friends, social media. It has amazed me how people are feeling such immense pressure and stress but are still willing to share, connect and donate their time. Some people I’ve found, have felt desperate to be heard during the silences of the lockdown.

This week, I’m releasing one on gender-based violence and coronavirus, and one with newly qualified nurses. Coming up, we have episodes on whether there will be a financial crash after the pandemic, the psychology of lockdown, and on death and grief with some ‘death positivity’ activists. I am also hoping to do an episode looking at sociological approaches to conspiracy theories. It is a time for us to listen as well as talk, to understand rather than laugh or judge, to observe rather than over-analyse. This is what the podcast is aiming to do and what I think our wider role as sociologists needs to return to more often. It aims to find a balanced, calm, serious – but at the same time, informal and light-hearted – approach to the crisis. I want it to contribute to academic material that isn’t just focused on the production of knowledge. I want to help, in my own, tiny way, to cut through some of the panic and hyper-anxiety and help bring shreds of reflection and clarity whilst also lifting the voices of those that need to be heard right now. It is a panicked time, yes, but where we can find our own small corners to do so, we can find ways to connect with ourselves and others and choose not to live in constant misery.

It goes without saying that COVID-19 is only partially a health crisis. In my recent article on women and the virus, I talk in-depth about how it is a political, economic, social, institutional and gendered crisis. The podcast wants to cover the less-represented angles of all this. What is happening to sex workers right now? What do supermarket workers think when they’re off shift? How does lockdown shine a light on patriarchy? How can we bear the grief this time brings? I want it to bring something a bit more human than a paper would have allowed me to do. I’m also recording short readings from some of my favourite books on the podcast – it’s cheesy, but what better time to go on a personal journey? I don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow to me or anyone I know or love, so I want to share some of the writers and subject matters that have shaped who I am.

I have learnt a lot about myself whilst being in four walls for a few weeks. One of the biggest learnings is that life can whizz by me when I’m working multiple jobs and unfortunately I don’t get much time and space to go ‘yeah. That thing you did – that was great’. The most surprising thing is the self-realisation that has come from the project. I have learnt I am resourceful, resilient, compassionate, forgiving, and could be way less hard on myself. I hope I can continue on that upwards trajectory of not shedding my self-doubt. I wish that for you, too.

You can find the Difficult Conversations podcast on Youtube, with new episodes being added weekly. It will soon move to Spotify once I have mastered it.

Martin Booker

While more and more people are wearing literal face masks, metaphorically it is quite a different picture: For many of the things widely considered normal, routine, and unchangeable, the mask is truly off! Our taken-for-granted reality has been exposed as what it always was, a social construction, not set in stone, but something that can be changed. This includes everyday activities of how we relate to other people, how we do our shopping, how we move through public spaces, how we work in offices and teach in classrooms. But it also applies to bigger issues. There is a growing awareness of the importance of ‘key workers’ that keep our economy going, an almost Marxian awakening that it is not the bosses but the workers that create the value. There has been a shift from a slightly naive version of ‘we’re all in this together’ – often heard in the early stages of the lockdown – to a growing awareness that the pandemic affects people differently and very unequally, and this has a lot to do with class, race and gender. Inequalities and socio-economic conflct lines, hidden as they were behind the thin veneer of ‘normality’, are now more visible than ever.

Call me an optimist, but in all this malaise, there seem to me the beginnings of something that could turn out to be very positive. There is common thread running through all these debates and discourses, a shift in perception, a re-thinking of – and this is what makes me optimistic – the relationship between individual and society. Whether this is about social distancing measures (in which we are all asked individually to contribute to a greater good), our shopping habits (only buying what we need, so there is more left for others), an increased concern for local businesses, a revival of political interest (with citizens eagerly comparing their leaders’ covid responses to those of others), the clap-for-the-carers events, or the surge in volunteering – what all these have in common is that individuals here don’t see themselves as isolated, but within a wider social context. By stealth, there has been a shift in perception, an ontological realignment if you like.

To the sociologist, this brings to mind what C. Wright Mills famously called the Sociological Imagination – as he argued, we should think of our private problems not just as private problems, but also be aware of how they form part of a bigger whole, of public issues. In the times of pandemic this could mean an awareness of how being stuck in my flat all day (my private problem) is important for the wider (public) issue of containing the virus, or, say, you are young and healthy and don’t really have too much to fear from the virus personally, but still feel the need to socially distance, out of solidarity with those more at risk. A growing interest in statistics and data, too, shows an increased attention to the bigger picture beyond one’s personal experience. And while we are all sitting in our living rooms twiddling thumbs, learning new hobbies, struggling to be productive, writing blogs, or dealing with writing block, we know exactly that so many others are doing the same, for the same reasons, an army of stay-at-homers, a collective fate of sorts.

This, of course, is not just a shift in perception. It is also an increase in understanding. Our lives have always been, and will always be, shaped by our social contexts. As sociologists, we’re in the business of pointing this out. And, of course, we can only shape these contexts in positive ways if we are aware of them, and of how they work. The mask is off for now. Things will go back to some kind of normal at some point. Here is hoping, however, that this shift in awareness is real, and will last.

Martin Booker is Teaching Fellow at Edinburgh University. He is writing from Abbeyhill, Edinburgh, and has found a new appreciation for the wild beauty of Holyrood Park, for his socially-distanced daily exercise.

Sophia Woodman

This pandemic, and the responses of universities to it, are providing a fascinating on-going natural experiment for thinking through what higher education is/should be for. During the UCU strike in February and March this year, I was reading more than was healthy about plans in some quarters to turn universities into platforms through which students consume information, ‘teaching’, food, entertainment, accommodation, sport—in other words, everything. And how during such processes, universities can hoover up data about these students to enable ‘smarter’ responses to their needs—including for mental health interventions.

For some time, university leaders have been warned that EdTech is going to make them redundant, because students as ‘digital natives’ will opt for the customized, individualized, efficient (and cheaper) ‘learning’ the EdTech companies are offering. Generally, the proponents of digitization assume that the best (or only?) way for universities to take on this challenge is to compete with the EdTech companies at their own game—to give the customers what they want. And of course, the EdTech companies are only too happy to help with these processes of transforming the university; platformization involves various forms of public-private partnerships. Just like other big tech firms, EdTech companies will be big winners from the coronavirus fall out.

We don’t know yet how this experiment will play out, but it seems peculiar to me that university managers would be willing to accept the above ‘if you can’t beat them, join them’ premise. I’m completely convinced by Raewyn Connell’s arguments in her marvellous, witty and readable new book, The Good University: what universities actually do and why it’s time for radical change. She argues that knowledge production has to be cooperative, and that cooperation is built into the DNA of universities. Intellectual labour, she writes, is inherently collective and requires cooperation, not just among academics and students, but also with what she calls the ‘operations staff’ who enable the working of the university. The ‘banking model’ of education on which the EdTech vision sketched out above is based is obviously contrary to the idea of a knowledge commons where multiple ‘knowledge formations’ are constantly being constructed and transformed through collective efforts, processes that are fundamentally at odds with the university as business, which seeks to extract profit from such efforts.

I know my most inspiring times in the classroom have been those in which students and teachers are learning together, and the end points are not fixed. So, in the coming months, we’ll see. Watch this space.

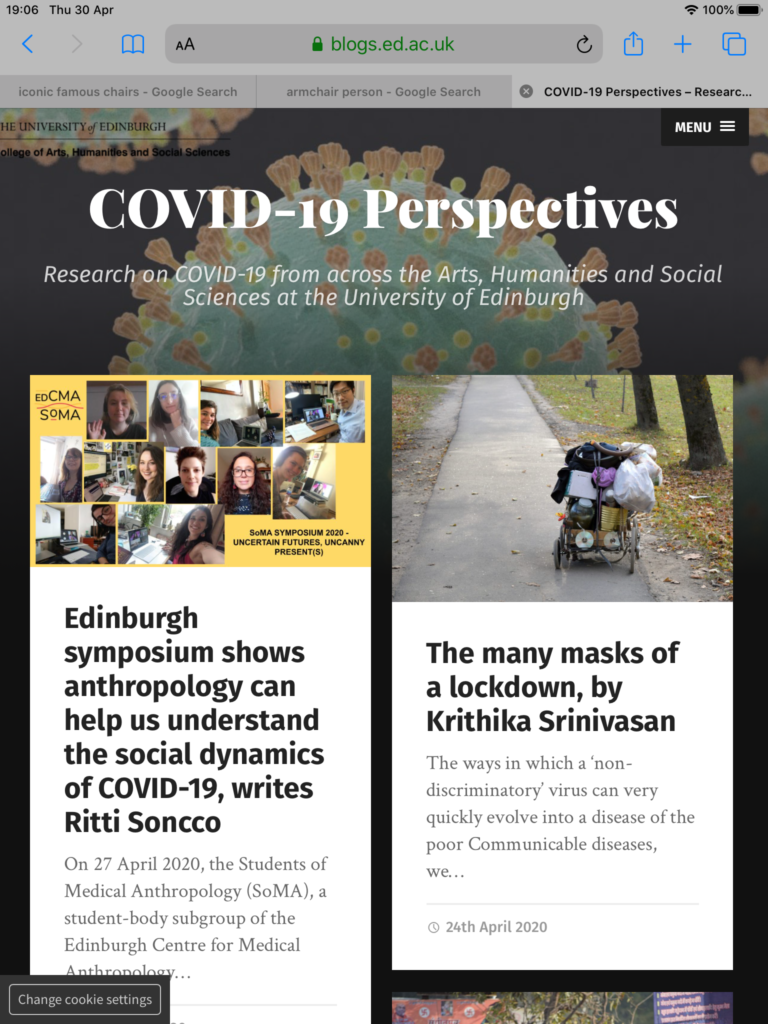

Liz Stanley

It reflects, but in a mediated and inverted way. It is an apparatus and is human-made. It also requires a person to look and see.

Emilia Sereva

Greetings from the Connecticut woods! Lately, I have been preoccupied by logistical topics to do with supply chain management. I never thought I’d experience supply chain disruptions in a grocery store here, because, well, this is America and we’re #1 (note my sarcasm, please), but of course I now stand corrected. This has been a problem for would-be grocery shoppers the world over, who can hopefully relate the predicament I find myself in when trying to sort out a week’s worth of meals for my family. I have been endeavouring to only grocery shop once a week at most, and although it’s true that we all try to visit grocery stores as infrequently as is possible out of consideration for the health of ourselves and others, that becomes difficult if we cannot find enough food in one trip. It’s alarming to see stripped shelves at the local grocery store, although it’s understandable why shoppers would buy in larger quantities than they otherwise would when scarcity is a concern. Before the lockdowns and the supply chain issues, I would normally buy in bulk wherever possible to avoid unnecessary trips, but now I buy only what I need with other shoppers in mind. I’m surprised to learn I care about other people? I wonder what that’s about. My ‘new normal’ now includes trolling eBay for a decently-priced economy size pack of freezer storage bags, or else spending hours looking for an online distributor who sells flour that I’m not allergic to.

Here is my side of food-related conversation from earlier today, which would have seemed odd on several levels out of the present context: ‘I would suggest we pick up some Aubergine Parmesan for dinner, but the butcher who makes the cook-and-serve kind we like is only accepting curb-side pickup orders now, and orders must be placed the night before, so that’s out. I also thought of making scrambled eggs on toast, but we don’t have enough of them and I’d rather not go to the grocery store just to buy some eggs’ (which, by the way, are now 4x their pre-pandemic price). These sorts of conversations between household members point up the ‘new normal’ we keep hearing about. Thinking sociologically, what is ‘normal’ anyway? In this situation that we are all faced with, the best thing to do is to adapt rather than compare or pine.

Presented with limited options, I find myself concocting comforting dinner ideas on the fly based on what ingredients I can amass. I think the present problem of never knowing what will be on offer at the grocery store has definitely made us all a bit more grateful for what we do have, and has also provided many opportunities for ingenuity and out-of-the-box thinking.

‘What’s for dinner tonight? I’m making what we once called breakfast (because who cares anymore what things are called?): Blueberry pancakes and bacon!

Here’s the pancake batter recipe I use, just in case you’d like to make some too.

Liz Stanley

It is the late 1340s and a pandemic – the Black Death, the bubonic plague – is raging. Increased numbers of people are dying day on day, no one knows how to stop it, friends and family shun each other, the ordinary sense of time and space and social connectedness is dislocated. A group of acquaintances, seven women and three men, come together, deciding to isolate themselves from the city for a two-week quarantine period and to do so in a thoughtful and mindful way. They gather together for the lockdown period. And they tell each other stories, the stories of their times – 10 days, 10 people, 100 stories. This is the setting for Boccaccio’s The Decameron.

Even people who don’t know anything much about The Decameron [the hundred stories] beyond its title have often heard of ‘patient Griselda’, a folklore figure, as well as appearing in this book. Griselda is a woman who bears no anger or resentment, no matter how ill-treated she is by the pig of a man she is married to; and she appears in the last of its stories, the tenth story told on the tenth day. However, from the (symbolic) names of its ten storytelling characters, through to the time and place of the stories they tell, there is little about the contents of The Decameron that can be taken straightforwardly at face value.

The final story is that of patient Griselda, but it is impossible to think that the book’s seven feisty women storytellers would have been anything other than impatient and annoyed with such a misogynistic idea of what a perfect woman would be like – thought of on the surface Griselda is a bully’s wet dream, and in her case the bully-husband is the Marquis of Saluzzo while she was a peasant by birth. In our present pandemic times, the figural ‘she’ here has a particular resonance, given the vast increase in domestic violence that is being recorded in current lockdown circumstances in many different parts of the world. So why does the book close with this, at the point where the assembled ten storytellers are about to return to Florence and the plague? What point are readers are expected to take from it?

All the ten last stories in The Decameron are about good and bad behaviour in sexual, marital and other relationships, so it is possible to read it as the swinish husband being a way of heaping praise on the more than perfect conduct of Griselda, a goody two-shoes if ever there was one, indeed so perfectly forgiving as to be quite impossible. But while it is preceded by nine other good conduct stories, it is immediately followed by an epilogue which provides another way of understanding it. In the ‘Author’s conclusion’, Boccaccio steps forth and directly addresses the reader, which the authorial ‘he’ does earlier in the book too. He says that these are stories of the times, they deal with things that happen although they may infringe how things are spoken and written about in more ordinary circumstances (with this directed most to the bawdy sexual content of a number of them), that ‘the ladies’ who he is addressing should take from them the lessons they want, and that his intentions as an author are signalled in the ‘sign on its brow’ over each of the stories. This is the summary or abstract that proceeds each of the hundred stories. In the case of patient Griselda, the ‘sign on its brow’ is in effect entirely about the husband and his ill-conduct. His misogyny is defeated in the end by her perfections, she is celebrated as the heroine of hour, she enters glory in the city of Saluzzo.

But what of now? A Griselda for our time is not a textual device for pointing up and ‘rescuing’ the ill-behaviour of men. A Griselda for our time is a very, very impatient woman. She views the upturn in domestic violence towards women as appalling. She notes that the vast majority of frontline care work in the present pandemic is being done by badly paid women. For impatient Griselda there is no return to the city, she probably heads for a domestic violence refuge somewhere – or perhaps she becomes a care worker.

Contributors should have a past or present association with the University of Edinburgh. Please see what appears on the Home page for ideas about the wide range of different kinds of contributions that can be made.

Ideas for contributions and contributions themselves should be directed to the relevant curator, or if in doubt to Angus Bancroft or Liz Stanley. Name and affiliation should be placed at the end of the contribution and sent by email and file attachment.

Liz Stanley

As in many places, the small village of Warton turns out on Thursday nights at 8 PM, to clap the NHS and care workers. I recorded the 23 April great clap – it’s a two minute MP3 recording of a quite extraordinary thing, because almost everybody in the village turns out and the sound echoes all round. It’s the only time we see anyone not from our own households now, the only time we talk. And the age range is phenomenal, from three months old to a month short of 90. Two minutes of togetherness apart.