Giulia Cavalcanti

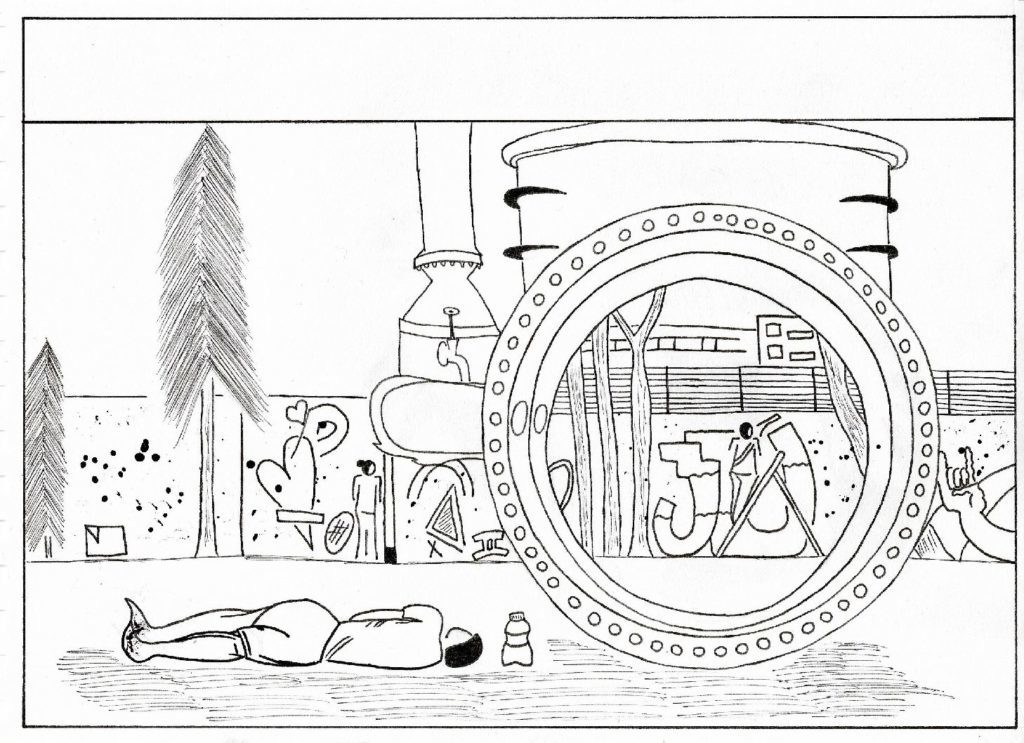

I befriended a homeless man.

It is interesting how I am choosing to write about this. This is not a ‘hero’ story. This is just a story about an ordinary human being. Me.

Yet, it is interesting how this act has remained etched in my mind.

In ‘normal’ times where we run late to work, class or to socialise with everyone apart ourselves and/or strangers, so focused on our routines and ourselves, this story is worth telling. Bear in mind, this is not a story about a homeless man, it is a story about myself…

I befriended a homeless man.

I am no hero. I am human. Coronavirus made me human. Coronavirus made us all humans. Once again.

I walk to the shop near my home and there he is. A man around his 40s, with grey short hair and beard. Always sitting with crossed legs, smiling and wishing everyone ‘a good day’. A British or Scottish version of George Clooney I must say. I am sure he was there many times before and during Coronavirus, before and after I noticed him. Always there. I must have seen him, smiled embarrassed and mumbled something like “I’m sorry”. But then one day – nothing like an epiphany – while I am walking to the shop from the safety of my home, I do wonder ‘how it is like to live under the skin of a homeless person?’. What is interesting is that only now with Coronavirus I asked myself such a question.

As now in light of the movement of Black Lives Matter, many people – including myself – ask themselves ‘how it is like to live under the skin of a black person?’. Only now, or only when some big media explodes.

Yet, Coronavirus did not cause homelessness. Coronavirus simply changed my relation towards homeless people. Homelessness has always been there, I was simply not looking directly at it. The reason most likely is that now the home is so filled with meaning and with a bit of intersectional lens we can become all aware that even the literal meaning of home is not as granted as we thought it was. It actually has never been granted!

My “epiphany” changed my attitude. I started smiling, with real intent of smiling, without embarrassment. I started looking and seeing this man’s face. I was no longer simply looking towards his face. I saw the man’s face, and notices: the short grey beard, his small eyes, small details…

I made soup and I brought it to him. I talked to him – What would you like?

And he said nothing. I was confused.

Sometimes I would ask, sometimes I would “surprise” him. Sometimes he would answer secure of what he wanted, sometimes he would not know.

Coffee.

Chocolate.

I did not buy him something every time. But he smiled at me every time. And I smiled and waved at him every time.

He was a kind man. Those people that give you the impression of calmness.

And then I realised something. I did not behave with all homeless people in the same way. That was not an epiphany moment at all. I still smiled embarrassed and mumble “I’m sorry” to other homeless people. I still did not look at every homeless people directly in the eyes. I would wait until he was there to buy something. I bought a coffee once to another homeless man. But that’s it.

So… Why him? It was not the George Clooney’s clone charm. Rather I choose to humanise that singular man. I choose to give him a face into my memory. I choose to interact with him. I choose to connect with him.

There is always something about humanising one homeless person. Usually a man. Homeless women do exist, you know. And yet again women are the one whose stories, whose existence do not change us rich white folks. I still wonder why we choose one person. And why did I choose him? And, after going over and over what I wrote I have my answer. I do not particularly like this ‘solution’. But here it is! I choose him because he does not look like the homeless person. He does not have the appearance of abusing substances of any sorts. He looks clean. He looks at you. He says: ‘have a good day’ before someone would mumble ‘I’m sorry’. He could be a male version of myself as homeless.

I choose him because our similarities allowed me to empathise with him. I did not choose consciously, but I think my unconscious drove me to him for some reason…

Until our culture is ready to humanise everyone. Every single person. And not just the ones who look like us – Capitalism will win. And every time we walk to a shop and do not see the person who is sitting outside on the floor, capitalism will have won the battle.

I befriended a homeless man.

I humanised a homeless man.

I wish I had asked him more.

– What happened?

– What’s your name?

I still do not know his name.

So, after all, this is a short story about my failed attempt to befriend a homeless man. So, after all, this is a short story of how a virus humanised one woman and maybe all citizens overall.