Ashley Barnwell

Unable to visit, I speak to my favourite four-year old via video-chat. She exhibits her latest crayon portraits. I ask her if she has been to the park. Her brow furrows with confusion – surely this adult knows about …? Just in case, she breaks the news, “Have you heard about the virus? You can’t go anywhere.” Later she sends a whatsapp voice-recording on her mother’s phone that says, “I want to go”. The word stretches out. Go somewhere, go anywhere.

People are using space differently. With the walls closing in, home blurs into the street. Neighbours I’ve never seen are outside. A young woman, two houses down, drags her desk out to the footpath and reads a textbook with her back to the sun. On the corner at night a man jumps rope under the streetlight, like a strange apparition. The lads across the road leave their blinds open and our living rooms look into each other, the glow of lights and the flicker of televisions assure that life is still living beyond the walls.

In the absence of my daily routine, I find myself missing people I don’t know. The people who also catch the 8.38am tram. The always-chipper barista at the stop who knows all their names and preferred milks. I see these people more often than I see my family. In another way, they are familiar to me. Suddenly it feels meaningful that we show up each morning and signify for one another the start of a day going to plan so far, same crew, no surprises yet.

Habits are hard to break. In the fruit market a mother reminds her two boys to “practice keeping their hands in their pockets”. Upon hearing this, I have already picked up and squeezed and put back several too-ripe avocados. Hands touching things touching hands.

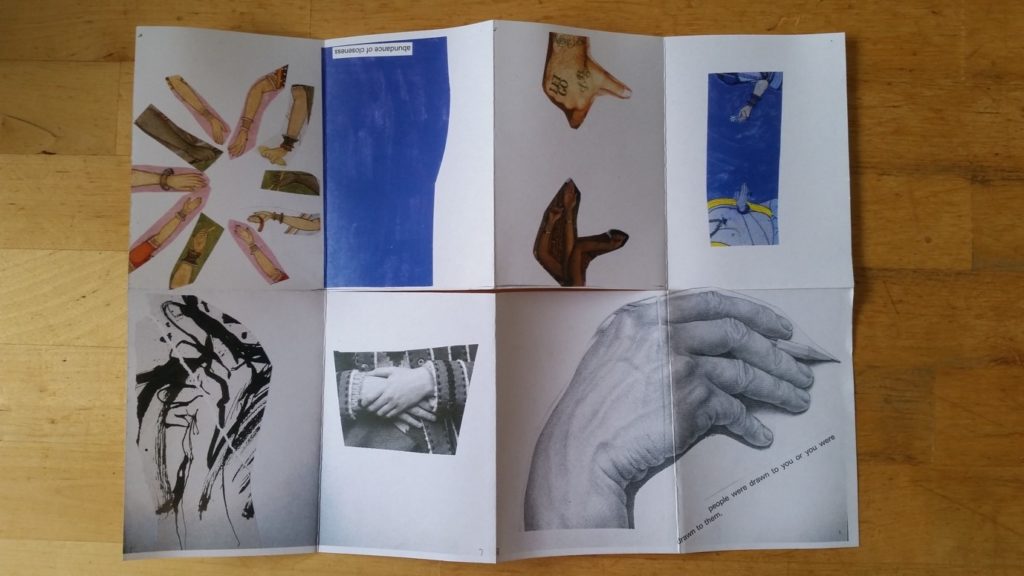

Over the summer I was thinking about hands (for pre-corona reasons). I made a little zine about them, and showed it to an old friend. He said he almost wrote a book about hands being the very end of us, the part that touches the world. We sat in the bar and watched what people do with their hands. Always reaching out, tipping a glass, offering a light, acting out a story, and then closing the circuit, bringing the hand back to the self, to clasp, rub a shoulder, pick a tooth.

The news app says medics are ‘tracing contacts’. If infected, we’ll be asked to remember all the tiny touches and transfers that happen every hour. We tap the same buttons, open the same doors, exchange the same coins, breathe the same air. To forget this, we stage ‘personal space’ with collaborative acts and cues. Standing so close we feel the heat of each other’s bodies during commuter hour, we gaze down, put bags between us, listen to headphones. Now the trams roll by empty.

During lockdown, the state permits a daily walk in the local neighbourhood for exercise. Usually (in the old normal) I walk to get somewhere. I dash from the office to buy a sandwich. I race to a committee meeting at 7 minutes past the hour. I roam the aisles of the supermarket hungry to get home. A to B. B to A. Now (in the new normal) I walk to walk.

It feels properly solitary to walk for the sake of walking. But on these walks I have been thinking about intimacy, albeit of an impersonal kind. What is our ethical duty to people we’ve never met? The social ground that is now a figure.

I have been mulling on this because the question newly envelops us. It is the small print on all government bulletins, ‘how-to-handwash’ signs, graphs of available respirators, in each political speech and on every absurd protest banner. But my thoughts have also been sparked by the signs of neighbourliness that punctuate the path.

I walk alongside the Moonee Ponds Creek, one of the main tributaries of the Yarra River. A rich source of life and culture for the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nations, the waterway flows from the mountains to the sea. In the colonial construction of Melbourne the creek was diverted and its marshlands filled with refuse and then concrete. On the stretch that winds through the inner north of the city, people jog and cycle along what is now a vast concrete stormwater-drain, funnelling the waters under and around the Tullamarine Freeway and down to the Docks. Graffiti and water-logged litter line the trail. It is urban, but in its expanse also feels scenic. As you cross under the shadowy 8-lane overpass, the echo of cars speeding above is damp and booming.

Most people walk alone or with dogs, but all around there are flashes of community. Old tyres bridge the muddy dips in the path. A donated dining chair sits under the rungs of the overpass surveying the bend. Teddy bears peer down from windows backing onto the creek, as part of a crowd-sourced bear hunt to entertain isolated kids. The way is furnished with the care of strangers.

Walking north, you come to a little library made for passers-by. Named the Waxman Lockdown Library (or WLL) for the street, it is housed in an old bedside cabinet, and decorated with love-hearts and bookish quotes from the likes of Frank Zappa and Anon. The shelf is stocked with scandi-noirs and half-read classics. In faithful charity, the top drawer offers necessities which are now scarce due to panic buying – toilet rolls and sachets of hand-sanitiser. The little library is a beacon in pandemic times. It feels fragile in its risk of transfer yet defiant in its ethos of trust and sharing.

Returning south, the concrete gullies are blazoned with graffiti. I notice a new piece this week, simple in line style and bold in proclamation – “I will not take dictation from you”. It recalls a famous retort from a former cabinet minister to a conservative radio shock-jock. It’s a reminder of the toxic tangle of media and politics. It’s a reminder of all the toxic tangles we have been struggling to break from, all the battles that go on neglected while we pour our attention into this crisis – the violence of gender binaries; neo-colonial rule; climate injustice. The red letters reach out like someone shaking me from sleep.

Perhaps it is the isolation, the break from routine, the halt of busyness, that allows me to feel these impersonal intimacies more sharply. In staying home to save lives we’ve assumed a responsibility for the wellbeing of people we don’t know and will never meet. As I walk, hands in pockets, I wonder what we will make of this chance to see the usually unseen ties that bind us?

Ashley Barnwell is a Sociologist at the University of Melbourne. In 2019 she was a visiting scholar in Sociology at the University of Edinburgh.