Morena Tartari

Once upon a time, there was a mother and a son. The mother was a researcher. Her work carried them to different countries in Europe to study the problems of someone who was a mother like her. She considered herself lucky compared to many mothers she had met for her research: she had studied, had a job, and a healthy son. However, having to compete for academic work with men and women without children, the mother never rested, never cried, her thoughts never stopped, her fatigue was so great, her face marked, her hair whitened.

The son was a primary school pupil. Travelling he had learned a new language and had listened to many others. He loved stories, nature, and science. His humor was a valuable resource and adults and children usually loved him.

Together, the mother and the son had started from a Mediterranean country, Italy, where they had left a grandmother and friends. If the child sometimes felt nostalgic for their home, the mother had no nostalgia for the efforts made to make ends meet. From Italy, they had migrated to Belgium and soon left for Scotland, which was just outside the borders of Europe.

In Scotland, they had immediately felt at home. The son loved school and classmates. The mother adored colleagues; he wrote and worked tirelessly. People were hospitable. Nature was intriguing. It was all they had always wanted.

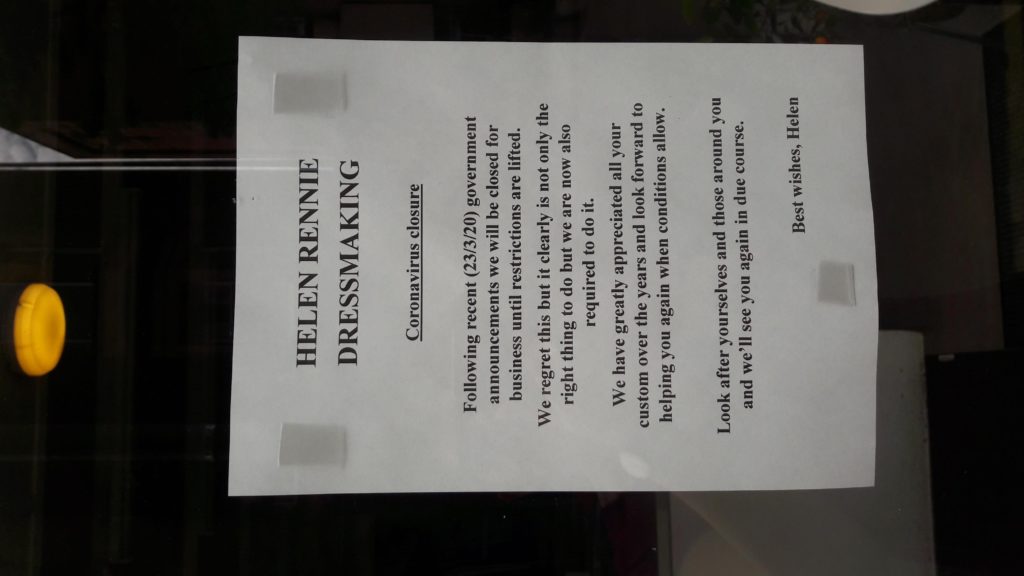

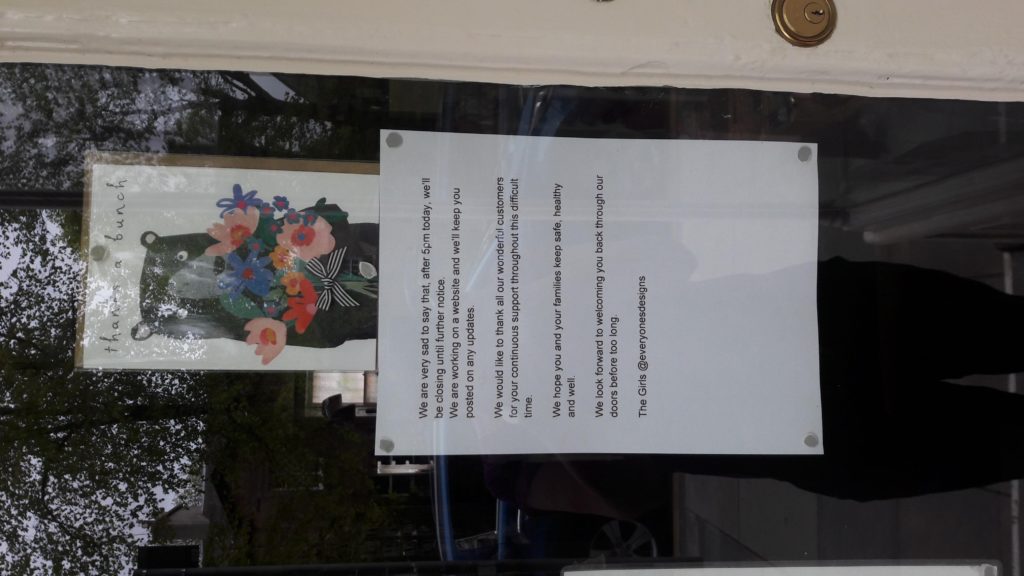

But an epidemic came.

Perhaps read about only in schoolbooks, for many the word epidemic had an ancient sound. Frequent comparisons were made with the Spanish plague and fever, but most seemed to have forgotten what an epidemic was. Having studied ancient Greek, the mother knew that ἐπιδημία (epidemìa) is something that “is in the people”, circulates, takes possession of them, governs them, does not discriminate, but exacerbates inequalities.

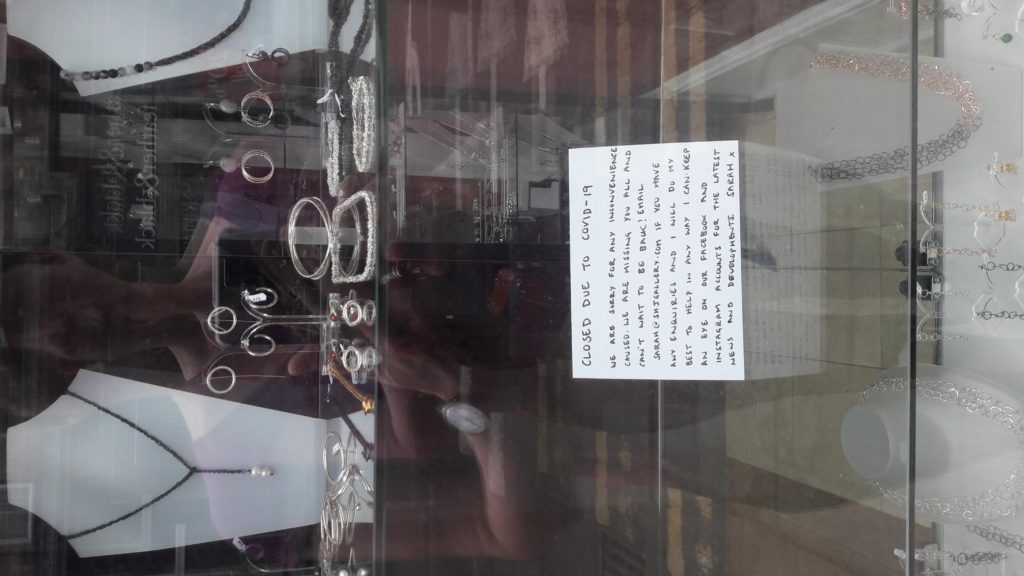

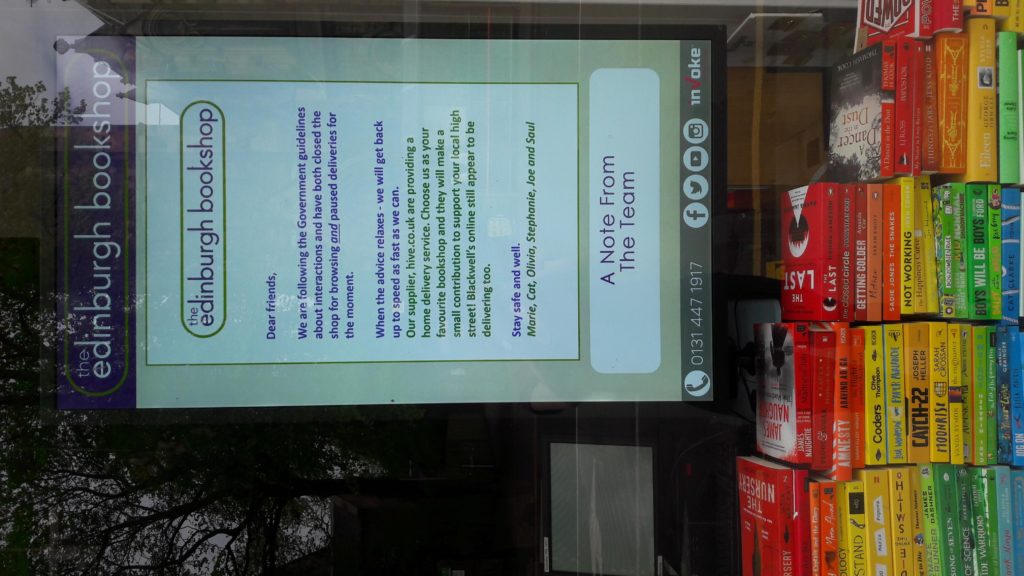

In Italy, the epidemic had spread early and quickly compared to other countries. In other countries, it had come more slowly. In others, it was spreading. However, the life of the mother and son flowed normally, in that Scottish city, hospitable and rich in culture, where the mother and the son could not give up cinemas and theaters, libraries and book stores, museums and gardens. The virus seemed nonexistent. It was enough to think so.

In those weeks between February and March 2020, among the people that the mother met in that city, the epidemic was discussed as an invention of the mass media, a non-existent danger, a constructed panic, an economic speculation, a normal flu, a mistake by the Mediterranean countries, which were considered unable to manage economic and health resources.

In social media in Italy in those same weeks, the epidemic was considered as an enemy invasion, the result of uncontrolled and dangerous immigration, the result of a conspiracy. Furthermore, some people celebrated the epidemic as a liberation brought to humanity: it freed old and sick souls to facilitate their renewal. It “cleaned”.

The mother and the son were unable to fully experience the feelings of their compatriots: skepticism, the anger of being invaded by an “immigrant” virus, anxiety about health, the terror of being deprived of personal freedoms, the fear of contagion among those who had chronic diseases. The mother and the son were unable to understand the abnormality of the situation.

One morning in March, while her son was at school, the mother returned home to get some documents and stopped for a few moments to read the news from her country. On the web page of a newspaper, she saw a video: in the night a column of army trucks transported dozens of corpses out of an ancient town to many other towns, because no cemetery had more place to house the dead, for the cremations there were long waiting lists. The video was silent, only the noise of the engines running. Faced with those images, the mother sat down and began to cry. She could only cry. It was not important that they were elderly or sick. They were dead. In the following weeks, the dead multiplied.

The following weeks seemed endless. For the mother, media and social media were simultaneous windows on the social realities of the country from which they came, Italy, of the one in which they resided, Belgium, and of the one in which they were, the UK. The windows opened contradictory views: the naturalness and the artificiality of the virus, underestimation and overestimation of the danger, hundreds of deaths, a few deaths, different preventive measures, distances of one meter, distances of two meters, open schools, closed schools, seven-day quarantine, fourteen-day quarantine, closed borders, open borders. Each country was developing its own beliefs. In Belgium, it was happening what almost a month earlier the mother had seen it happen in Italy and that she expected would happen – and then it happened – in the UK. It was like living and reliving a déjà-vu.

One afternoon in March, the son came home from school and said to his mother, “My classmates beat me because I am Italian and they say that I brought the virus here. But we, mom, went to Italy only for Christmas.” It seemed to the son and mother that a spell had broken. But they didn’t tell each other. They felt alone in a foreign country.

The announcement of the restrictive measures finally came. The first few days after the announcement, many women the mother had in her contacts lost their jobs. They were mostly single mothers, with a single income. They fell one after the other, like apples from the tree of the precariousness, shouting their despair to acquaintances and strangers through Facebook. There were women who wanted to hide their condition for fear of losing their children. Women who had no money for rent, taxes, groceries. Women who could not go out to do their shopping being alone with young children. Women who feared to die from the virus and leaving orphaned children. Women who made a will. Women who, with joint custody, feared that the coming and going between their home and that of their former partner would facilitate contagion.

Working was difficult for the mother. Time went by looking for information on the virus, on the restrictive measures themselves, on the number of deaths, on the forecasts. It was a whirlwind of one’s own and others’ thoughts.

Later, with a child in primary school and a closed school, the mother was able to work a few hours during the day and a few hours during the night. She accumulated tiredness and worries in her bones, but she continued to feel lucky to be able to work from home.

One day in May, a board denied her a publication because she sent it four days after the deadline. Explaining her family circumstances did not help. At the end of the pandemic – she thought – childless men and women would emerge victorious in the academic competition. Perhaps she too, shortly thereafter, would fall from the tree of precariousness.

Despite everything, the lockdown also presented opportunities. The immobility of staying at home allowed the mother and son saving two or three hours a day by not traveling and commuting. Therefore, there was a lot of time to talk, explain, remember, plan, dream together. Working online from home allowed them to multiply the opportunities in the geographical space: she attended seminars and workshops in the United States or Australia while sitting in their living room, and her son online attended his school in Belgium and video called his classmates in Italy.

The mother rediscovered many childhood memories and taught her son what her father – a primary school teacher – had taught her. In other times, he would not have had time to regain possession of these memories and turn them into new learning.

But, above all, the mother and the son could walk in the meadows and parks, whose colors, after hours and hours closed in the house, shone extraordinarily. Being able to go out once a day in a powerful spring meant making many discoveries that started from the ground on which they placed their feet up to the sky beyond the branches of the trees. They felt free to breathe, look, touch, and listen. They felt they were citizens of a natural world without borders. They wished that their ideas could spread without borders, feeling everywhere at home, free to become part of every living thing: like a virus.

Together they were writing a will.

About the author

Morena Tartari is, currently, a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Research Fellow at the Department of Sociology, University of Antwerp, Belgium. https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/staff/morena-tartari/

She is carrying out a comparative research study (STRESS-Mums) in four European Countries about single mothers and judicial institutions. In 2012, she completed her Ph.D. (Sociology) at the University of Padua, Italy. During the Covid-19 pandemic, she was a visiting Research Fellow at the School of Social and Political Science of The University of Edinburgh and she participated as a postgraduate student in the discussions sparked by Lynn Jamieson’s sociology class on Intimate Relationships.