How listening to African children can advance access to justice in the climate crisis

Author: Liesl Muller

PhD researcher with the Youth Climate Justice Project at University College Cork, funded by the European Research Council (grant agreement 101088453)

Children’s climate litigation has boomed in the last 10 years. According to the University College Cork Youth Climate Justice project’s case law database, approximately 81 climate cases have been launched by children and youth, or on their behalf, in countries all over the world in the past decade. These cases include child applicants as young as 7 years and under, but the majority fall within the 13 to 18 years range.[1] They often act alongside young adults up to age 25, and some of them reach adulthood while the case is pending, thus the term child/youth-involved climate litigation.

The surge in child/youth-involved climate litigation is fuelled by governments’ failure to sufficiently address children’s climate concerns. Children face floods, heatwaves, pollution, illness, and climate anxiety. These harms violate their rights to health, life, dignity, education, a healthy environment and more, and they feel like their governments are not taking sufficient measures to address this. Children as a group are more seriously impacted by climate change harms than arguably any other grouping, especially children in Africa.[2] And yet they are underrepresented in environmental decision-making because they do not vote and are often ignored in public consultations. It is no surprise, then, that children are turning to courts as their last option for protection.

Courts can provide legally binding decisions when other methods fail, but the effectiveness of this remedy depends on whether children have access to the courts. They have a right to access justice and an effective remedy, but research shows that children face significant barriers in their access to justice generally. Court processes are not tailored to children’s specific needs, and they have limited access to relevant information. Climate-specific cases pose further difficulty in that courts are reluctant to tackle climate change, arguing, for instance, that it is too global and universal a problem for them to address in individual cases. They also argue that the child applicants do not suffer a unique individual harm, because everyone is affected by climate change. As a result, only about one-third of child/youth-involved climate cases have been successful so far. Thirteen cases had never been heard, and others had been pending before the courts, some for as long as 14 years! This is not access to justice for children. Some even argue that it amounts to discrimination against children based on their age.[3]

Twenty-four of the child/youth-involved climate cases have been dismissed on procedural grounds before being heard in court. These include preliminary issues like admissibility, standing, and justiciability, among others. The famous Juliana v US case was dismissed after 10 years in court, with lawyers arguing about whether the courts are capable of addressing the alleged harm (redressability). It meant that the child applicants, none of whom were still children at the end, were never allowed to present their full evidence to the court. The Juliana courts, and others globally, apply strict procedural rules, without referring to the child’s right to equality, to have their views heard and considered, and to access justice. This failure to engage with children’s rights in the procedural phase is a violation of children’s rights and must be addressed.

Courts must urgently start applying a child rights approach to procedural rules in child/youth-involved climate cases. This means they must put the best interests of children first; listen to children’s views and take them seriously; make remedies available, accessible, and child-friendly; relax strict rules when they stop children from getting justice; allow group cases, broad standing, and flexible proof rules; and move cases forward quickly, because delays harm children more. UN standards, such as the Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General Comment 26 on children’s rights and the environment, with a special focus on climate change, support these ideas.

South Africa has a long history of human rights and public interest litigation. Two principles which have evolved from it may also be able to help children: transformative constitutionalism and ubuntu. South Africa’s first democratic Constitution allows broad standing, enabling almost anyone to approach a court to protect human rights, even if they have not been harmed themselves. This has led to some interesting climate-related cases where the South African High Court confirmed that children can even go to court to protect the interests of unborn future generations, regardless of whether they themselves have suffered harm. The courts have interpreted the Constitution liberally, or purposively, to extend the limits of who can bring a case. A purposive interpretation means the court applies an interpretation that gives effect to the object and purpose of the law, rather than a strict literal meaning. The courts have developed a rich jurisprudence in favour of relaxing procedural rules, allowing applicants to vindicate their rights, which is the object of the constitution.

The second principle, ubuntu, is the Southern African version of an age-old African philosophy which values community, connection, and shared responsibility. In one sentence, it means: “I am because you are”. It understands that our well-being depends on each other and the environment. It is found in African human rights instruments and jurisprudence, and it has played a key role in South African cases as an interpretive lens for its new Constitution. Children have adopted solidarity as a key element in their climate work globally – this is a fundamental aspect of ubuntu. In the South African case known as Cancel Coal, a youth-led organisation applied to court on behalf of all children, youth and future generations, to prevent a decision to use more coal for electricity from being executed. These and other youth cases emphasise how we are related to one another and nature, and that our well-being is connected. This approach may provide a basis for extending the limits of procedure to include better representation, as opposed to focusing solely on proving individual harm, as many courts do.

I recently published an article on this topic in the African Journal for Climate Law and Justice, called “Children at the lekgotla: African child-led litigation for remedies in the climate crisis”.[4] You can find an easy-read summary here, accessible to both children and adults, and the full text here. The article discusses children’s climate litigation as a critical avenue to seek remedies for the climate crisis. It highlights the challenges children face in accessing justice through courts, particularly due to stringent preliminary procedural hurdles such as demonstrating individual harm, proving direct causation, and issues related to redressability and separation of powers. It proposes adopting a child rights-based approach and integrating non-Western philosophies, such as South Africa’s ubuntu, to overcome these barriers. The article proposes that the emphasis on ubuntu’s interconnectedness and collective well-being offers a more suitable framework for addressing the complex, multi-generational nature of climate change in legal contexts. Engaging with children’s litigation presents an opportunity for courts to evolve legal frameworks, moving towards more inclusive and effective remedies for climate injustice globally.

“Lekgotla” is a Sesotho word for the traditional community council in Southern Africa, where important matters are discussed, and decisions are made collectively. Children have shown themselves to be leaders in addressing the climate crisis. Taking cases to court has given them the opportunity to speak at the lekgotla, and their contributions are beneficial to everyone. Ensuring that children have the opportunity to be heard on matters of climate governance will not only fulfil their human rights as equal citizens in society, but it will also benefit us all, leading to creative new solutions to problems which adults have not yet solved. African children offer a unique flavour of this contribution, which is well worth engaging at the lekgotla.

This research forms part of the Youth Climate Justice project, which is led by Prof. Aoife Daly and funded by the European Research Council (grant agreement 101088453). The project consists of a team of researchers who want to understand more about children and young people’s climate action across different countries and what this means for children’s rights.

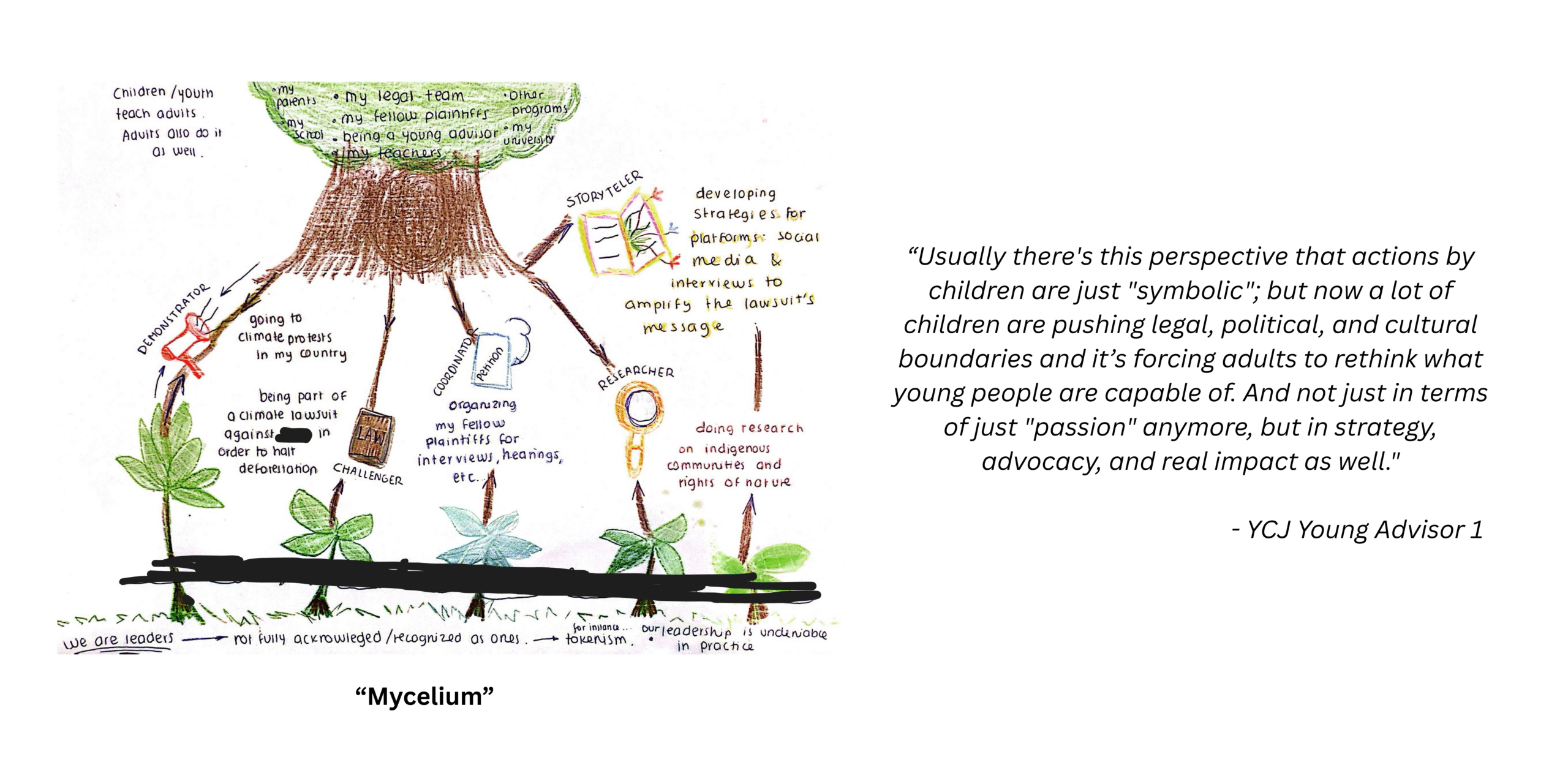

They look at cases children and young people have taken about the climate crisis, talk to children and young people who have been taking climate action, and hold creative workshops to understand what children think about their rights, the environment, and climate change. The project investigates whether we are experiencing ‘Postpaternalism’ in children’s rights.[5] We use the word post-paternalism to describe grassroots action from children and youth for the first time, on a global scale, rather than well-meaning adults ‘giving’ children and youth their rights.

References

[1] Daly, A. and Muller, L., 2025. Child/Youth Climate Litigation: Tracking Children’s Rights and Children’s Impact. Wash. & Lee L. Rev., 82, p.1049. 10.2139/ssrn.5431815.

[2] African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACERWC), 2024. ‘Study on climate change and children’s rights in Africa: A continental overview’.

[3] Daly, A (2025) “Chapter 7 Nondiscrimination/Equality and Children’s Rights in the Climate Crisis”. In Treated Like a Child https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004708433_008

[4] Muller, LH (2025) “Children at the lekgotla: African child-led litigation for remedies in the climate crisis” African Journal of Climate Law and Justice, 4, 59-92. 10.29053/ajclj.v2i1.0004.

[5] Daly, A.; Maharjan, N.; Montesinos Calvo-Fernández, E.; Muller, L.H.; Murray, E.M.; O’Sullivan, A.; Paz Landeira, F.; Reid, K. ‘Climate Action and the UNCRC: A ‘Postpaternalist’ World Where Children Claim Their Own Rights.’ Youth 2024, 4, 1387-1404. doi.org/10.3390/youth4040088.

Comments are closed

Comments to this thread have been closed by the post author or by an administrator.