I’m in North Wales for Easter, and the weather (hooray) has been nice enough to get out for a walk or two. I visited Prestatyn Hillside: an impressive north-west-facing limestone cliff.

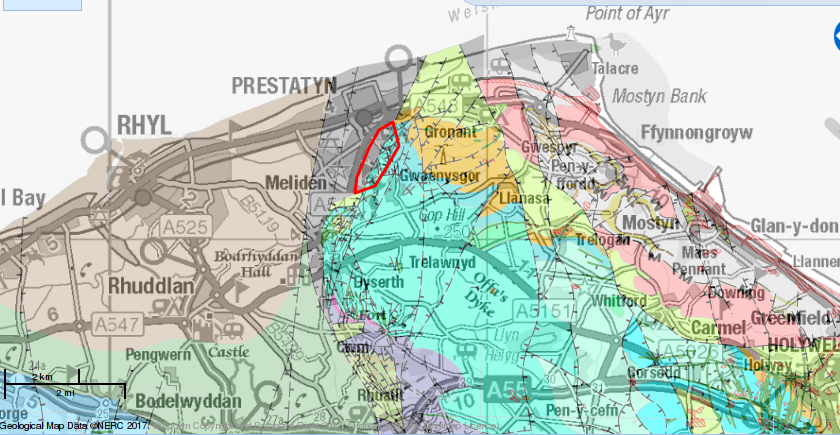

The limestone is of Visean age, towards the old end of the Carboniferous period; essentially the same rock that we spend a week on every three years on the geophysics field course, and that I visited in Yorkshire a few weeks ago. There is an extensive area of the limestone along the top of the Clwydian hills, but it comes to an abrupt end at Prestatyn, at a fault, the other side of which is newer sedimentary rocks from the young end of the Carboniferous period: the Coal measures, as it is called in older British geology books. Without reading up on it, I rather assume that the steep hillside is a landscape feature produced by the underlying geology, with the limestone being more resistant to erosion than the Coal Measures.

You can not see any of the Coal Measures rocks as they are underneath the flat coastal plan and the town of Prestatyn. The limestone is only visible in small areas on the wooded hillside, but there are various places where it has been quarried in the past, leaving spectacular exposures.

The bedding is quite close to horizontal, with well defined beds a few tens of centimetres thick. The quarry is one of those places where you can stare at the rock for ages and feel a real sense of the depth of geological time.

The beds are mostly flat, but in a few places you can see deformation on a scale of a few metres; my guess is that this occurred while the sediment was still soft, but I don’t claim to be an expert. The quarrying must have been a serious industry at some point; the woods are full of overgrown bits of industrial archaeology.

The industry was not limited to bulk limestone extraction either: the hillside contains several mineral veins which have been mined in the past for lead. I came across a shaft near the top of the hillside with a sizeable spoil heap below it.

The spoil clearly comes from a vein; it contains lots of vein quartz (right) and calcite (left).

The two minerals are easily distinguished by the shapes of the crystals and by the fact that the quartz will scratch the calcite, but not vice versa. (I forgot to put a scale in the photo; the larger crystals are about 1cm across.) I didn’t find any lead ore at all; either the vein was a dud, or the miners were very efficient at separating the ore from the rest of the material.