The drive down to North Wales for Easter meant one crossing of the England-Scotland border, so it seemed a good opportunity to visit all the crossings we didn’t have time for in part 1 of this two-part post. We packed the car and headed south across the borderlands, aiming for the A68, which crosses the border at Carter Bar.

The A68 goes through Jedburgh and then follows the deep valley of the Jed water before heading for the Cheviots. After a bit, you notice that you have left the rich farmland behind and are in an area of moorland and forest plantations, with the hills forming a continuous barrier in front of you. The road tackles the ascent in a series of sharp hairpin bends, eventually delivering you to the Carter Bar border crossing at the top of the pass.

Carter bar (crossing number 17 in my numbering scheme) is pretty much in the middle of nowhere, but it is quite a busy crossing. It is the only one apart from crossing number 1 on the A1 to have acquired English and Scottish flagpoles, modern stone monoliths and a snack van. It even has a souvenir salesman, operating out of the back of his car.

Mrs. Very Understanding Navigator decreed that, as I had dragged her out before her normal breakfast time, she was jolly well having a cup of tea and a bacon sandwich.

The view north into Scotland is stunning.

The view into England is far less inviting: it is just bleak heather moorland and the lie of the land means that you can not see very far.

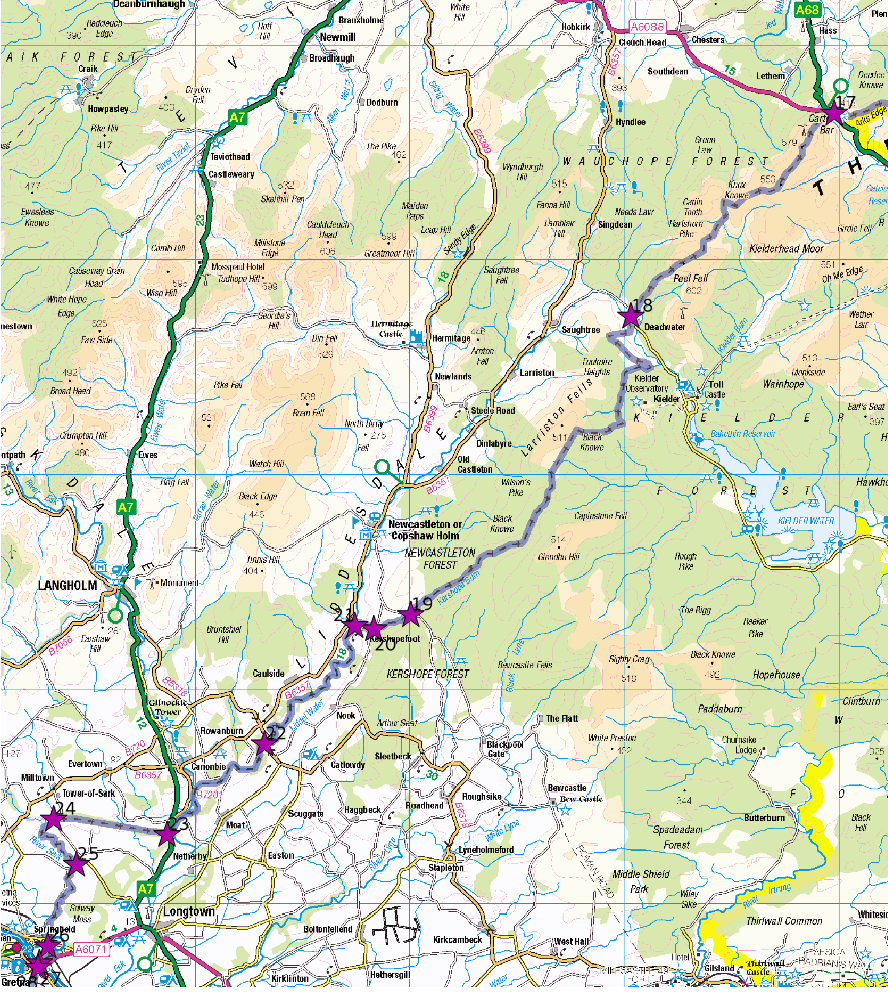

When the plan for this journey started to form in the back of my mind, I had intended to cross the border at each crossing, driving through England between crossings 1 and 2, through Scotland between crossings 2 and 3 etc. I gave this idea up on discovering that some of the crossings in the eastern half of the border were a bit complicated, with the border running along a road that had junctions with other roads. There is no such weirdness in the western half of the border, but there is a practical problem in that the English side of the border has few roads, and almost none that run parallel to the border. If you head into England from Carter Bar, you have to make a very long loop to end up at crossing 18. We therefore headed back into Scotland, taking the A6088 and the B6397, followed by a minor road that crosses the border at a place called Deadwater, which genuinely is in the middle of nowhere, with none of Carter Bar’s trappings of civilisation.

The England sign at this crossing looks very old and appears to be hand-painted. Presumably it has survived the attentions of vandals for so long because few people pass this way. It must be very weatherproof paint. The next three crossings (19-21) are a closely-spaced group, near the hamlet of Kershopefoot, about as far from crossing 18 as crossing 18 is from crossing 17. Again, we turned round at the border and drove through Scotland to crossing 19, which is this little bridge across the Kershope Burn.

I parked on the Scottish side and walked across the bridge to take the picture. It is not clear what the ruined brick buildings at the right of the picture are for; maybe they had something to do with the quarry that is behind them. Yet another about-turn back into Scotland took us to crossing 20. This is also a bridge across the Kershope Burn; the border follows the burn for a considerable distance. I didn’t get much of a picture because the only place I could stop was a passing place.

The crossing has no border signs at all. This time, we did actually cross the border and drive a short distance through England to crossing 21. I was a bit puzzled by the signage here: both the England and Scotland signs are a good distance to the west (England) side of the bridge over the Liddel Water; you can see the bridge in the distance in the picture.

Looking carefully at the map afterwards made it clear that the border is where you would expect it: in the middle of the river. Why the signs are not either side of the bridge is anybody’s guess. We drove back across the bridge into Scotland and headed for crossing 22. This is also a bridge, where the B6318 crosses the Liddel water. The view of England as one heads towards the bridge is considerably more appealing here than it is at Carter Bar. The bridge itself is easy to park at, and there is a footpath into the fields on the Scotland side, from where I could take a picture looking downriver. It would be a nice spot for a picnic.

Crossing 23 is less appealing: it is on the busy A7. It does have this nice little toll house, though.

The border reaches here by following the Liddel water to its confluence with the River Esk. It follows the Esk south for no more than half a kilometre before heading almost due west in a straight line. This section, between crossings 23 and 24, looks at odds with the rest of the border, even on a map with little detail. The 1:50000 map has the mysterious label “Scots Dike”; I had to restort to the internet to find out what this was. It appears that the border was very ill-defined in this region in the middle ages; there was a considerable area called the debatable lands in which the local noblemen waged tribal warfare. For a long time it suited both England and Scotland to have this buffer zone. Eventually, the authorities on both sides of the border became fed up with the situation and set up a committee, arbitrated by the French ambassador, to draw up a proper border. Having decided where the border was, they built an earth bank with a ditch either side to mark it; this earthwork is the Scots Dike. I imagine they also told the lairds either side of the dike to stay their own side and to stop treating the area as a cow-stealing theme park. This all happened in 1552, during the reigns of Mary Queen of Scots, and Edward VI of England, presumably making the Scots Dike the newest border earthwork in Britain. All the other examples I can think of are Roman (Antonine and Hadrian’s walls) or Saxon (Offa’s dyke in Wales, Fleam and Devil’s Dykes in East Anglia).

The next crossing (number 24) is at the other end of the Scots Dike, on a very small road. There are no border signs but the location of the border is fairly clear from the dense plantation of trees which cover the dike.

The picture is looking east along the north side of the dike from crossing 24. A quick foray into the (very dense) plantation showed no sign of the earthwork itself. The trees stop at the road, a little way short of where the line of the dike meets the little River Sark. The border follows the Sark from here to its end in the Solway Firth. Having approached crossing 24 from Scotland, we crossed into England, and then back into Scotland at crossing 25.

The picture is looking east along the north side of the dike from crossing 24. A quick foray into the (very dense) plantation showed no sign of the earthwork itself. The trees stop at the road, a little way short of where the line of the dike meets the little River Sark. The border follows the Sark from here to its end in the Solway Firth. Having approached crossing 24 from Scotland, we crossed into England, and then back into Scotland at crossing 25.

This bridge over the Sark also has no border crossing signs; the picture is looking northeast from Scotland into England. From here we drove through Scotland on a very narrow road that is part of a national cycle route as far as Gretna, where the last three crossings are. Crossing 26 has the entertaining name Plump Bridge; it is on a minor road now, but has the air of having been more important at some point.

The current road bridge is quite new; the previous bridge next to it is fenced off to cars, but was easy to access on foot. From here it is a short drive to crossings 27 and 28. Crossing 27 is the M6. We didn’t drive across it as we have done that many times, we satisfied ourselves with a brief glance from the bridge where the A6071 crosses the motorway. The final crossing, Sark Bridge, is very close by.

I was standing on the Scottish side of the crossing to take this picture.

So that is the lot: every drivable crossing visited. Many thanks are, of course, due to my long-suffering navigator. If you want to visit the crossings, you might want to do so now, before you are thwarted by scoundrel politicians and an unwise voting public.

One Reply to “Out on the border: part 2.”