Giulia Cavalcanti

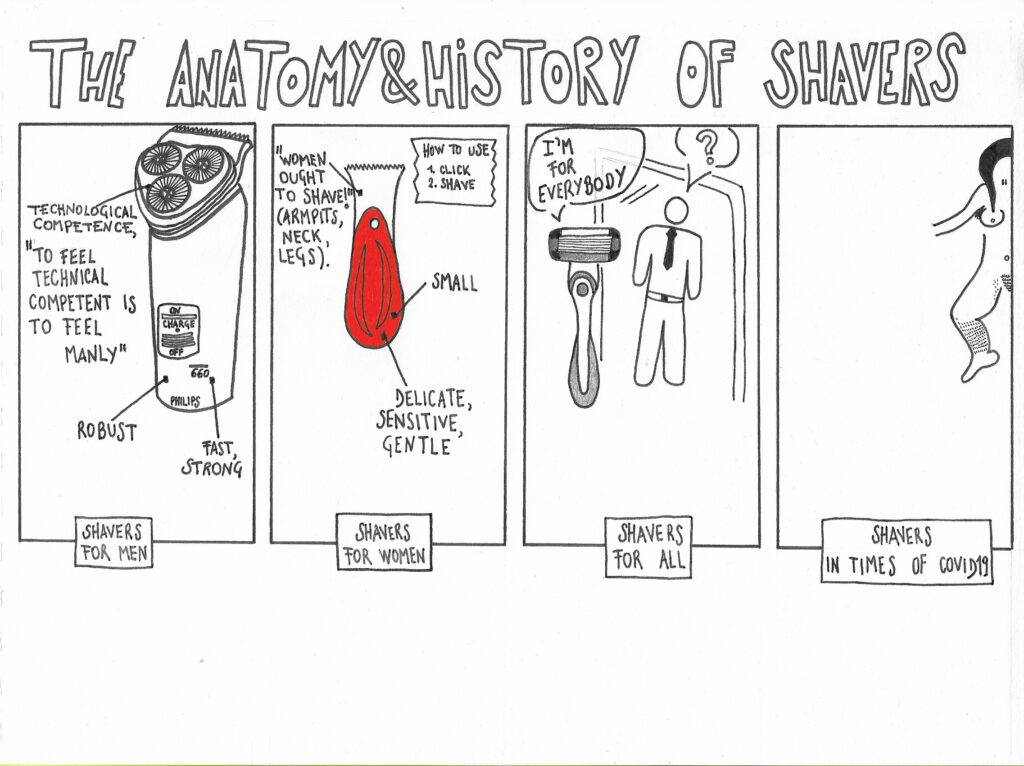

Today I will tell you the anatomy and history of electric shavers from 1920 until today, or better known as Corona times.

Shavers came into the world for men. Designed by men for men. Black, robust, strong, fast, and with visible screws. That is how electric shavers for men were and still look like (van Oost, 2003: 198-9). As sociologists, we are all well aware that material goods are used to construct and perform one’s gendered identity (van Oost, 2003: 194). This electric shaver advert from the 1990s targeted to men says it all. Meanwhile the manly voice talks, the song sings “for the men inside”. These features – robust, strong, fast, technological competent – are the features that make men manly. Masculinity, however, was not built from scratch starting from electric shavers. Designers and adverts have simply reinforced the meaning of being a man through the symbolic features of electric shavers ‘for men’. For instance, the visible screws told men that they are technologically competent (van Oost, 2003: 198-9, 207).

Then, shavers for women came into the world. For women, but yet still designed by men. Pink, small, delicate, sensitive, gentle. That is how electric shavers for women were and still look like. This was the understanding that designers – male designers – had around femininity. Small, delicate, sensitive, gentle ‘electric shavers for women’ alongside their adverts — such as this – have reinforced the meaning of being a woman (van Oost, 2003: 200-7). Furthermore, the manly voice in the advert gives us a tip. He says: “made for women with men in mind”. Simply put, women ought to shave for the pleasure of men. And this is how women’s generation after generation dedicated their times to remove their body hair to avoid men from having the haunting sight of a hairy woman, meanwhile hairy men became sexier and sexier…

Eventually, millennials came into the world and rejected the gendered products, including shavers. Designers and adverts had to respond, and eventually, gender-neutral shavers came into the world. Shavers ‘for you’, shavers ‘for all’… But how neutral are they? If we take a closer look and compare those “revolutionary” (feel the sarcasm) shavers and compare them to the old-fashion ‘shavers for men’, it can be easily argued that gender-neutral shavers or any other “neutral” material good, are made having in mind as possible target men, exactly because designers are mostly male (van Oost, 2003: 196).

Products have changed, but not shaving practices, especially among women. Until finally, coronavirus or scientifically speaking COVID-19 came. Coronavirus has contributed to making the poor poorer, black deaths, working-class peoples’ deaths, increased housework and childcare labour for women…. But we, or at least I, cannot deny that coronavirus freed us all from few gendered social norms.

I haven’t worn a bra since lockdown.

I haven’t used make-up since lockdown.

I haven’t shaved since lockdown.

My neck, armpits, and legs are uncovered. It is summer. And yet I still have not shaved since lockdown. Has coronavirus revolutionised women’s shaving practices? The answer is no. I haven’t shaved since lockdown. Until I decided to go to Portobello beach to swim with my friends. Since then my body hair has grown, and I haven’t shaved since.

Yet, my neck, armpits, and legs continue to be uncovered. So, why have I shaved when I wore a bikini and not when I wear trousers that show my hairy legs? I wish I could say that the answer is laziness. Lazy to shave. Rather, one of the possible answers might be the fear of drawing attention. A female hairy body draws more attention than a shaved one. And drawing attention means having eyes at you. I shaved to not draw attention to my body, to limit the eyes of those who may look at my body. Because most than often drawing attention to a body ends in the sexualisation of it.

Let me tell you a story. I went to the Meadows and wore 80s trousers. For fashion lovers: black and white striped trousers. And a tight basic blacktop. I chose to wear those trousers despite my hairy legs, but I chose to wear a bra (remember: I haven’t worn a bra since lockdown, no matter if at home, or outside).I chose to show my hairy legs, but I chose to hide my nipples. Calves, in my heterosexual viewpoint, are not sexy. Calves are not sexual per se. Women’s nipples are.

This is when choosing what to wear for a simple walk at the meadows with a friend becomes a sociology class. So, what has led me to step outside the door of my house wearing a bra? I chose my outfit. I tried it on. And I saw my nipples. So far so good. But then, a body sensation filled my whole body. Anxiety. Fear. Of what? – you may ask. Fear of being sexualised. Fear of the eyes of those who may sexualise free nipples. This was the same fear and anxiety that led me to shave my legs before going for a swim at the beach.

The truth is that I shaved when I wore a bikini to protect myself. The truth is that I wore a bra to protect myself. The ugly truth is that women juggle between making themselves sexual beings and desexualise themselves to avoid over-sexualisation anytime, anywhere by anyone.

Let me tell you a final little story. The other day was the birthday of my friend, and we celebrated at the Meadows, once again. I wore a loose green shirt. I also chose to not wear a bra, despite being able to see my nipples and the shape of my breast at the mirror. I did it on purpose. Apart from a few drinks, I wanted to go back home with a sociological self-reflection. And I did. After all, I did not feel sexualised by anyone, including by the strangers that I encountered in the streets.

So, what was all the fuss about – you may ask? The ugly truth is that women and girls are taught that danger is everywhere, you must never let the guard down…

Covid-19, or corona as we informally call this killing virus, has not revolutionised women’s shaving practices. Women are simply standing against the gendered norms, as far as they, we, feel safe to do so. As far as rape culture will be round and about, hidden as coronavirus, around the streets and houses of the world, women’s revolution will not be completed.

Sources

van Oost, E. C. J. (2003). Materialized gender: how shavers configure the users’ feminity and masculinity. In N. E. J. Oudshoorn, & T. Pinch (Eds.), How users matter. The co-construction of users and technology (pp. 193-208). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.