Liz Stanley

All neighbours were present and correct and not ill or worrying they are. Next week‘s Clap will be the last, so watch this space.

Liz Stanley

All neighbours were present and correct and not ill or worrying they are. Next week‘s Clap will be the last, so watch this space.

Ashley Barnwell

Unable to visit, I speak to my favourite four-year old via video-chat. She exhibits her latest crayon portraits. I ask her if she has been to the park. Her brow furrows with confusion – surely this adult knows about …? Just in case, she breaks the news, “Have you heard about the virus? You can’t go anywhere.” Later she sends a whatsapp voice-recording on her mother’s phone that says, “I want to go”. The word stretches out. Go somewhere, go anywhere.

People are using space differently. With the walls closing in, home blurs into the street. Neighbours I’ve never seen are outside. A young woman, two houses down, drags her desk out to the footpath and reads a textbook with her back to the sun. On the corner at night a man jumps rope under the streetlight, like a strange apparition. The lads across the road leave their blinds open and our living rooms look into each other, the glow of lights and the flicker of televisions assure that life is still living beyond the walls.

In the absence of my daily routine, I find myself missing people I don’t know. The people who also catch the 8.38am tram. The always-chipper barista at the stop who knows all their names and preferred milks. I see these people more often than I see my family. In another way, they are familiar to me. Suddenly it feels meaningful that we show up each morning and signify for one another the start of a day going to plan so far, same crew, no surprises yet.

Habits are hard to break. In the fruit market a mother reminds her two boys to “practice keeping their hands in their pockets”. Upon hearing this, I have already picked up and squeezed and put back several too-ripe avocados. Hands touching things touching hands.

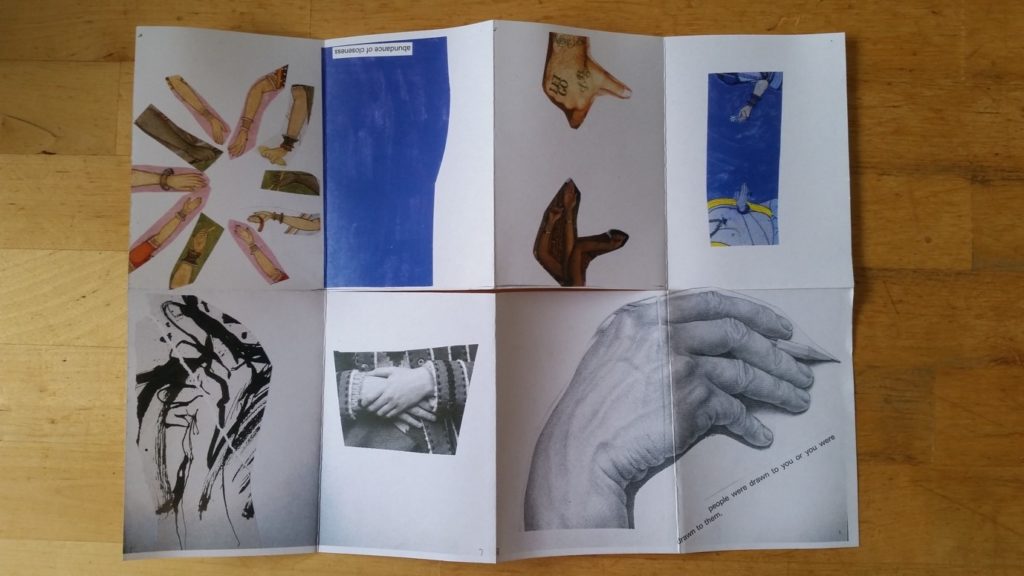

Over the summer I was thinking about hands (for pre-corona reasons). I made a little zine about them, and showed it to an old friend. He said he almost wrote a book about hands being the very end of us, the part that touches the world. We sat in the bar and watched what people do with their hands. Always reaching out, tipping a glass, offering a light, acting out a story, and then closing the circuit, bringing the hand back to the self, to clasp, rub a shoulder, pick a tooth.

The news app says medics are ‘tracing contacts’. If infected, we’ll be asked to remember all the tiny touches and transfers that happen every hour. We tap the same buttons, open the same doors, exchange the same coins, breathe the same air. To forget this, we stage ‘personal space’ with collaborative acts and cues. Standing so close we feel the heat of each other’s bodies during commuter hour, we gaze down, put bags between us, listen to headphones. Now the trams roll by empty.

During lockdown, the state permits a daily walk in the local neighbourhood for exercise. Usually (in the old normal) I walk to get somewhere. I dash from the office to buy a sandwich. I race to a committee meeting at 7 minutes past the hour. I roam the aisles of the supermarket hungry to get home. A to B. B to A. Now (in the new normal) I walk to walk.

It feels properly solitary to walk for the sake of walking. But on these walks I have been thinking about intimacy, albeit of an impersonal kind. What is our ethical duty to people we’ve never met? The social ground that is now a figure.

I have been mulling on this because the question newly envelops us. It is the small print on all government bulletins, ‘how-to-handwash’ signs, graphs of available respirators, in each political speech and on every absurd protest banner. But my thoughts have also been sparked by the signs of neighbourliness that punctuate the path.

I walk alongside the Moonee Ponds Creek, one of the main tributaries of the Yarra River. A rich source of life and culture for the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nations, the waterway flows from the mountains to the sea. In the colonial construction of Melbourne the creek was diverted and its marshlands filled with refuse and then concrete. On the stretch that winds through the inner north of the city, people jog and cycle along what is now a vast concrete stormwater-drain, funnelling the waters under and around the Tullamarine Freeway and down to the Docks. Graffiti and water-logged litter line the trail. It is urban, but in its expanse also feels scenic. As you cross under the shadowy 8-lane overpass, the echo of cars speeding above is damp and booming.

Most people walk alone or with dogs, but all around there are flashes of community. Old tyres bridge the muddy dips in the path. A donated dining chair sits under the rungs of the overpass surveying the bend. Teddy bears peer down from windows backing onto the creek, as part of a crowd-sourced bear hunt to entertain isolated kids. The way is furnished with the care of strangers.

Walking north, you come to a little library made for passers-by. Named the Waxman Lockdown Library (or WLL) for the street, it is housed in an old bedside cabinet, and decorated with love-hearts and bookish quotes from the likes of Frank Zappa and Anon. The shelf is stocked with scandi-noirs and half-read classics. In faithful charity, the top drawer offers necessities which are now scarce due to panic buying – toilet rolls and sachets of hand-sanitiser. The little library is a beacon in pandemic times. It feels fragile in its risk of transfer yet defiant in its ethos of trust and sharing.

Returning south, the concrete gullies are blazoned with graffiti. I notice a new piece this week, simple in line style and bold in proclamation – “I will not take dictation from you”. It recalls a famous retort from a former cabinet minister to a conservative radio shock-jock. It’s a reminder of the toxic tangle of media and politics. It’s a reminder of all the toxic tangles we have been struggling to break from, all the battles that go on neglected while we pour our attention into this crisis – the violence of gender binaries; neo-colonial rule; climate injustice. The red letters reach out like someone shaking me from sleep.

Perhaps it is the isolation, the break from routine, the halt of busyness, that allows me to feel these impersonal intimacies more sharply. In staying home to save lives we’ve assumed a responsibility for the wellbeing of people we don’t know and will never meet. As I walk, hands in pockets, I wonder what we will make of this chance to see the usually unseen ties that bind us?

Ashley Barnwell is a Sociologist at the University of Melbourne. In 2019 she was a visiting scholar in Sociology at the University of Edinburgh.

Elsie Greenwood

The past two months have been like no other in my life, the way society has disintegrated and changed has been remarkable. In many respects these developments are a sociologist’s dream – humanity, our systems of rule and particularly our political “harmony” has been exposed for what it is: impermanent.

When I watched the PM’s recent coronavirus update I sat in disbelief, the government line was both bewildering yet blatant in its ambition. It seemed non-sensical, never explaining what it actually meant to “stay alert”, yet brazenly saying those who cannot work from home are “actively encouraged” to return to employment before any workplace safety guidance had been released. To me, this read as: “we are succumbing to the desires of the liberal middle classes and will let them sunbathe and see friends in the park whilst we will keep the economy trudging along on the backs of the working class”. Because who are those unable to work from home? It’s the cleaners, factory workers, delivery drivers and builders.

The PM’s class-less analysis of his new policy didn’t stop there, he also gave recommendation to not use public transport to travel to work. 70% of working-class people in London use public transport to get to work, most Glaswegians don’t have a car, it was no surprise the news headlines following the PM’s updates were vilifying workers “pilling onto tubes”- as if no one could have predicted such an outcome. It’s hard to understand if the government is feckless or if they genuinely see working lives as dispensable?

When contemplating such a question as the one above, we should question why we use the use of the terms “key worker” and “hero” when referring to front line workers. Whilst I am obviously in awe of the working people risking their lives during this crisis, I find issue with these terms for particular reason. I worry they are a form of comfort blanket to help those of us sat at home moralise and justify people dying for us. When a key worker dies, it is tragic, but for some reason isn’t shocking. Whilst I will note we have been doing this since the war, it’s time we stop glorifying the deaths (of frequently working-class people) in times of crisis instead of asking the government why they aren’t doing more to protect working lives.

Now contrary to the opinion of many leftist men I encounter on twitter the working class isn’t just white men and thus we mustn’t white wash the problems Coronavirus has exposed. The virus is having a devastating impact amongst the working class BAME community – who have been disproportionately affected by the virus. Black men and women are dying at 4 times the rate of their white contemporaries, and 72% of our “key” NHS workers and carer deaths are BAME. The government needs to recognise they continually fail these communities: whether it’s Grenfell or Coronavirus, BAME communities are being hurt by the negligence of the British state.

Truthfully, the outcomes of this pandemic could have been predicted. The way the world works is unsurprising, class inequality permeates every corner of society, if austerity hurts the working classes the most, why wouldn’t a global pandemic?

But, we aren’t without hope.

If the coronavirus has done anything it has thrown societies biggest issues on to the front page of every newspaper, it has made the low skilled worker the key worker. The governments ability to change policy overnight has shown us it doesn’t have to be this way. This could be the time we actually start valuing those workers who are the backbone of this country, not just with an applause but with decent pay. I believe the system is shaking in its foundations, and time is up for those who think society has to be this way.

Elsie Greenwood is a undergraduate sociology student going into her third year at Edinburgh. She has been an active member of the Labour Party for 5 years and is co-chair of LGBT Labour in Scotland. She is a member of GMB the trade union and is on the Scottish Trade Union Youth Committee as the GMB representative. Some of her academic interests include: racial and class inequalities in the justice system, policing and social housing.

Sophia Woodman

When I first moved to Tianjin in northeast China with my family for 10 months of PhD fieldwork, people I met often offered suggestions about how to navigate the city, including where to shop. Several of them pointed out the location of Carrefour, a global French supermarket chain that had a superstore a bus ride away from where we lived. Their assumption was that this was the most appropriate shopping location for someone like me from what they called the ‘advanced’ world, and that I would be worried about the safety of places where locals did their shopping.

Just down the road, about five minutes’ walk from our flat, was the Tianjin version of a ‘wet market’—a commonplace in many Asian countries. In this city, by the time I moved there in 2008, long-standing local street markets had been moved into large covered halls, open at each end, with shop-like stalls along each side and tables stacked with produce down the middle. When you walked in to the main entrance to the market, the first stalls were piled high with colourful displays of all kinds of fruit, and a bit further down were vegetable sellers, who purveyed an impressive range of greens at all times of year. At the far end there were butchers, with red lights shining on cuts of meat hanging from hooks on a metal bar. There was no wild game in sight—this was not an upmarket neighbourhood. The market stretched out into the open along contiguous alleyways, with one along the side selling clothing, another household goods, flowers, plants and pets, among other things. There were tailors, watch repairers, cooked food vendors and bakers selling delicious flatbreads steaming from the griddle.

We often bought these flatbreads for lunch. We frequently ate it along with the cooked wares from a north China version of a salad bar: vinegar pickled vegetables—lotus root, spicy marinated cucumber, grated carrots—and cold potato flour noodles in toasted sesame paste sauce were among my favourites. A woman and her husband prepared the dishes, presumably at home or in the back of the stall. We bought all our fruit and veg in the market, and got to know which vendors sold the nicest and freshest produce. One of the vendors I liked most was a tall young man whose family came from a rural town some distance from Tianjin. He and his family sold all kinds of things that I didn’t recognize on their vegetable stall, and he would patiently explain to me how to cook them. One example was the spring tips of ash branches, which were delicious stir fried with egg, and like nothing else I had tasted. He always had a joke and often gave his regular customers an addition to what they had paid for, along with the standard handful of spring onions and leaves of fresh coriander.

I did occasionally shop at Carrefour, but I didn’t like it much. There was nothing social about the interactions in such supermarkets, and I didn’t find that the packaging and the sterile environment made me more trustful of the safety of what I was buying. I got into the habit, like most of my neighbours, of shopping daily at the street market, buying small amounts of what I wanted to cook and eat that day. Fresh food, less packaging, less food waste and friendly chat to boot. I’ve also loved shopping in similar markets in Hong Kong and Chiangmai, and found comparable experiences in farmers’ markets in Vancouver and Edinburgh.

Since the suspected origin of the coronavirus outbreak was linked to a wet market in Wuhan where live animals were on sale, there have been constant calls for wet markets to be banned. Such calls conflate wet markets and the eating of wild game, and show little awareness of the complex interconnections involved in the emergence of zoonotic viruses such as Covid-19, which knowledgeable writers have attributed to the destruction of ecosystems on the ever-expanding frontiers of global capitalism. Attacking wet markets is often a cover for barely-disguised anti-Asian racism, and unfortunately most journalists feed into this by continuing to report on the origins of the pandemic in a simplistic way, as well as giving air time to ill-informed celebrities who repeat these tired tropes.

Morena Tartari

Once upon a time, there was a mother and a son. The mother was a researcher. Her work carried them to different countries in Europe to study the problems of someone who was a mother like her. She considered herself lucky compared to many mothers she had met for her research: she had studied, had a job, and a healthy son. However, having to compete for academic work with men and women without children, the mother never rested, never cried, her thoughts never stopped, her fatigue was so great, her face marked, her hair whitened.

The son was a primary school pupil. Travelling he had learned a new language and had listened to many others. He loved stories, nature, and science. His humor was a valuable resource and adults and children usually loved him.

Together, the mother and the son had started from a Mediterranean country, Italy, where they had left a grandmother and friends. If the child sometimes felt nostalgic for their home, the mother had no nostalgia for the efforts made to make ends meet. From Italy, they had migrated to Belgium and soon left for Scotland, which was just outside the borders of Europe.

In Scotland, they had immediately felt at home. The son loved school and classmates. The mother adored colleagues; he wrote and worked tirelessly. People were hospitable. Nature was intriguing. It was all they had always wanted.

But an epidemic came.

Perhaps read about only in schoolbooks, for many the word epidemic had an ancient sound. Frequent comparisons were made with the Spanish plague and fever, but most seemed to have forgotten what an epidemic was. Having studied ancient Greek, the mother knew that ἐπιδημία (epidemìa) is something that “is in the people”, circulates, takes possession of them, governs them, does not discriminate, but exacerbates inequalities.

In Italy, the epidemic had spread early and quickly compared to other countries. In other countries, it had come more slowly. In others, it was spreading. However, the life of the mother and son flowed normally, in that Scottish city, hospitable and rich in culture, where the mother and the son could not give up cinemas and theaters, libraries and book stores, museums and gardens. The virus seemed nonexistent. It was enough to think so.

In those weeks between February and March 2020, among the people that the mother met in that city, the epidemic was discussed as an invention of the mass media, a non-existent danger, a constructed panic, an economic speculation, a normal flu, a mistake by the Mediterranean countries, which were considered unable to manage economic and health resources.

In social media in Italy in those same weeks, the epidemic was considered as an enemy invasion, the result of uncontrolled and dangerous immigration, the result of a conspiracy. Furthermore, some people celebrated the epidemic as a liberation brought to humanity: it freed old and sick souls to facilitate their renewal. It “cleaned”.

The mother and the son were unable to fully experience the feelings of their compatriots: skepticism, the anger of being invaded by an “immigrant” virus, anxiety about health, the terror of being deprived of personal freedoms, the fear of contagion among those who had chronic diseases. The mother and the son were unable to understand the abnormality of the situation.

One morning in March, while her son was at school, the mother returned home to get some documents and stopped for a few moments to read the news from her country. On the web page of a newspaper, she saw a video: in the night a column of army trucks transported dozens of corpses out of an ancient town to many other towns, because no cemetery had more place to house the dead, for the cremations there were long waiting lists. The video was silent, only the noise of the engines running. Faced with those images, the mother sat down and began to cry. She could only cry. It was not important that they were elderly or sick. They were dead. In the following weeks, the dead multiplied.

The following weeks seemed endless. For the mother, media and social media were simultaneous windows on the social realities of the country from which they came, Italy, of the one in which they resided, Belgium, and of the one in which they were, the UK. The windows opened contradictory views: the naturalness and the artificiality of the virus, underestimation and overestimation of the danger, hundreds of deaths, a few deaths, different preventive measures, distances of one meter, distances of two meters, open schools, closed schools, seven-day quarantine, fourteen-day quarantine, closed borders, open borders. Each country was developing its own beliefs. In Belgium, it was happening what almost a month earlier the mother had seen it happen in Italy and that she expected would happen – and then it happened – in the UK. It was like living and reliving a déjà-vu.

One afternoon in March, the son came home from school and said to his mother, “My classmates beat me because I am Italian and they say that I brought the virus here. But we, mom, went to Italy only for Christmas.” It seemed to the son and mother that a spell had broken. But they didn’t tell each other. They felt alone in a foreign country.

The announcement of the restrictive measures finally came. The first few days after the announcement, many women the mother had in her contacts lost their jobs. They were mostly single mothers, with a single income. They fell one after the other, like apples from the tree of the precariousness, shouting their despair to acquaintances and strangers through Facebook. There were women who wanted to hide their condition for fear of losing their children. Women who had no money for rent, taxes, groceries. Women who could not go out to do their shopping being alone with young children. Women who feared to die from the virus and leaving orphaned children. Women who made a will. Women who, with joint custody, feared that the coming and going between their home and that of their former partner would facilitate contagion.

Working was difficult for the mother. Time went by looking for information on the virus, on the restrictive measures themselves, on the number of deaths, on the forecasts. It was a whirlwind of one’s own and others’ thoughts.

Later, with a child in primary school and a closed school, the mother was able to work a few hours during the day and a few hours during the night. She accumulated tiredness and worries in her bones, but she continued to feel lucky to be able to work from home.

One day in May, a board denied her a publication because she sent it four days after the deadline. Explaining her family circumstances did not help. At the end of the pandemic – she thought – childless men and women would emerge victorious in the academic competition. Perhaps she too, shortly thereafter, would fall from the tree of precariousness.

Despite everything, the lockdown also presented opportunities. The immobility of staying at home allowed the mother and son saving two or three hours a day by not traveling and commuting. Therefore, there was a lot of time to talk, explain, remember, plan, dream together. Working online from home allowed them to multiply the opportunities in the geographical space: she attended seminars and workshops in the United States or Australia while sitting in their living room, and her son online attended his school in Belgium and video called his classmates in Italy.

The mother rediscovered many childhood memories and taught her son what her father – a primary school teacher – had taught her. In other times, he would not have had time to regain possession of these memories and turn them into new learning.

But, above all, the mother and the son could walk in the meadows and parks, whose colors, after hours and hours closed in the house, shone extraordinarily. Being able to go out once a day in a powerful spring meant making many discoveries that started from the ground on which they placed their feet up to the sky beyond the branches of the trees. They felt free to breathe, look, touch, and listen. They felt they were citizens of a natural world without borders. They wished that their ideas could spread without borders, feeling everywhere at home, free to become part of every living thing: like a virus.

Together they were writing a will.

About the author

Morena Tartari is, currently, a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Research Fellow at the Department of Sociology, University of Antwerp, Belgium. https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/staff/morena-tartari/

She is carrying out a comparative research study (STRESS-Mums) in four European Countries about single mothers and judicial institutions. In 2012, she completed her Ph.D. (Sociology) at the University of Padua, Italy. During the Covid-19 pandemic, she was a visiting Research Fellow at the School of Social and Political Science of The University of Edinburgh and she participated as a postgraduate student in the discussions sparked by Lynn Jamieson’s sociology class on Intimate Relationships.

Liz Stanley

The Great Clap continues. Claps, car horns, saucepans, whistles, whooping, all ring out from different parts of Warton village. The mystery of last week’s missing neighbours is solved, they were standing behind a hedge worrying about infection but are well now.

Annette Hay and Mary Holmes

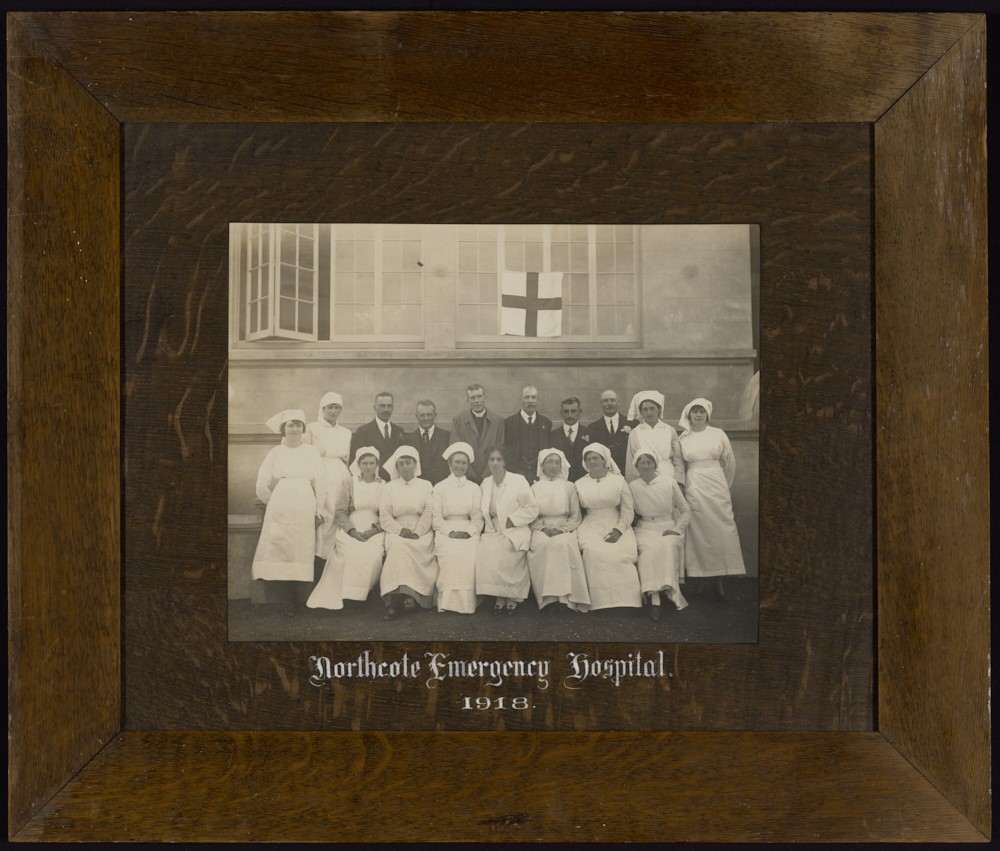

Annette Hay is an archivist and Special Collections librarian at the Auckland Public Library in New Zealand. Mary Holmes is a Professor in the Sociology Department at the University of Edinburgh. In the 1970s they attended Northcote Primary School together.

The big grey concrete building was a bit intimidating, but inside the classroom was big and lit up by huge windows. As we started school Annette’s great aunts delighted in telling her that she would be learning in a building that her great-grandfather had died in. Northcote Primary School, had been used as a temporary hospital in the 1918 influenza epidemic. That big grey building had only just been built, and as the flu hit New Zealand that November, it was quickly put into service.

There was a lesser wave of flu that went through the country some months before the bad one hit in late October 2018. The first wave affected the vulnerable: elderly, babies, and those with underlying illnesses. When the second more deadly wave arrived it killed off the healthy younger people, those in the 20 to 40 age group. One of the theories for this was that the more vulnerable who had caught and survived the first wave, had built up antibodies, and those who it hadn’t touched had no defence against the second wave. In just over two months the flu proceeded to kill around 9000 New Zealanders (the country’s population was around 1,150,000), hitting Maori communities particularly hard. There was a special graveyard created for Maori victims of the influenza in Northcote. It was at Awataha, near what is now Akoranga Drive. Some dispossessed Maori lived there in the early twentieth century, given sanctuary on land owned by the Catholic church until they were removed in the 1920s by the church and white settlers eager to more intensively farm and build on the land. Colonialism and wider world events played their part in the tragedies of the epidemic.

It is impossible to separate the story of the 1918 flu and the soldiers of World War I. As the war approached its eventual end on the 11 November, the stories of the epidemic are mixed up with the stories of returning soldiers. Annette’s grandfather, Will Hay, was one of those soldiers. In 1916 Will joined up and served with the New Zealand army in France, he survived gunshot wounds, gas and influenza, but arrived back in New Zealand at the end of 1918 to find that his father had died of the ‘Spanish Flu’ on the 25th of November, aged 51. Scottish born Balfour Hay had been nursed until he died in what became our primary school class room.

The epidemic was another blow to a country reeling from the loss of 18000 New Zealanders in WWI, but Northcote seemed to escape relatively lightly in the flu epidemic, with only 10 deaths in the official records. Like the current Covid 19 crisis, however, the count can be contested. For example, newly-wed Gladys Maxwell was from Northcote but died, aged 26, nursing her husband in a military training camp near Wellington. She was probably not counted in the Northcote toll. Nevertheless, it does seem that Northcote did not fare so badly. Why?

Northcote is a suburb of Auckland, NZ’s largest city, and now it is only 15 minutes drive across the harbour bridge to the city centre. But in 1918 there was no harbour bridge, although regular ferries ran to the city and the population of Northcote had grown to around 1600 – hence the need for a new school building.

Perhaps Northcote’s death toll was relatively low because the narrow piece of water between it and the city helped Northcote isolate? Perhaps it was because it was a village-like and almost semi-rural suburb (known for its strawberry growing) where most people were not wealthy but lived in comfort in houses on reasonable sized plots of land? They had some distance from each other and many grew vegetables. There were not the close together houses and poverty of some of the inner city suburbs that fared much worse. Perhaps however, being able to receive care locally may have made a difference, preventing locals who fell ill from having to go to the overfull Auckland Hospital. Perhaps the care people received in our primary school classrooms was so good that most recovered?

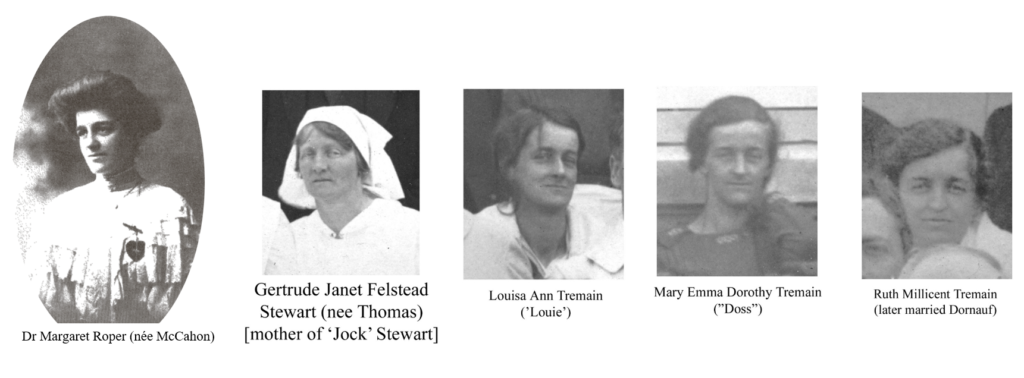

The mayor of neighbouring Birkenhead at the time was certainly reported in the Auckland Star as being of the opinion that without the efforts of staff at the hospital, there would have been many more deaths in the districts. He particularly thanked the Doctor in charge of the hospital, Dr Margaret McCahon (probably the woman in the middle of the front row of the framed photograph above), who later married and became Margaret Roper. Margaret, born in Timaru, in the South Island of New Zealand, was 36 at the time and she came with experience, having been medical inspector of schools for Otago and Southland and Medical Officer at St Helen’s Hospital in Auckland. Margaret was in charge of nurses and volunteers, including some of Annette’s great aunts Ruth, Doss and Louie Tremain and Gertrude Stewart – mother of ‘Jock’ Stewart, a close friend of Mary’s uncle. As it turns out, Margaret McCahon travelled abroad to do her medical training. She graduated MB ChB from the University of Edinburgh in 1908.

Somehow the big grey concrete building seemed haunted but not tainted by that epidemic. But that is just a memory. The building was demolished in the late 1970s, just over 50 years after it was built. The layout of separate classrooms was no longer thought appropriate for new ways of teaching. Of course, the point is not really to remember the building, but to remember the victims of the epidemic and the staff of nurses and volunteers who were under the direction of Margaret McCahon.

Sources

Auckland Star, (1918) ‘The Epidemic. Return to Normal. Northcote and Birkenhead Districts’, 2 December, page 6.

Rice, G. (2005) Black November: The 1918 influenza pandemic in New Zealand. Christchurch: Canterbury University Press.

Verran, D. (2006) ‘The Northcote Fuel Tank Farm to1989’, Speech given to the Birkenhead Historical Society, 13 May.

Wordsworth, J (1985) Women of Northern Wairoa. Orewa: Jane Wordsworth, pp 51 – 54.

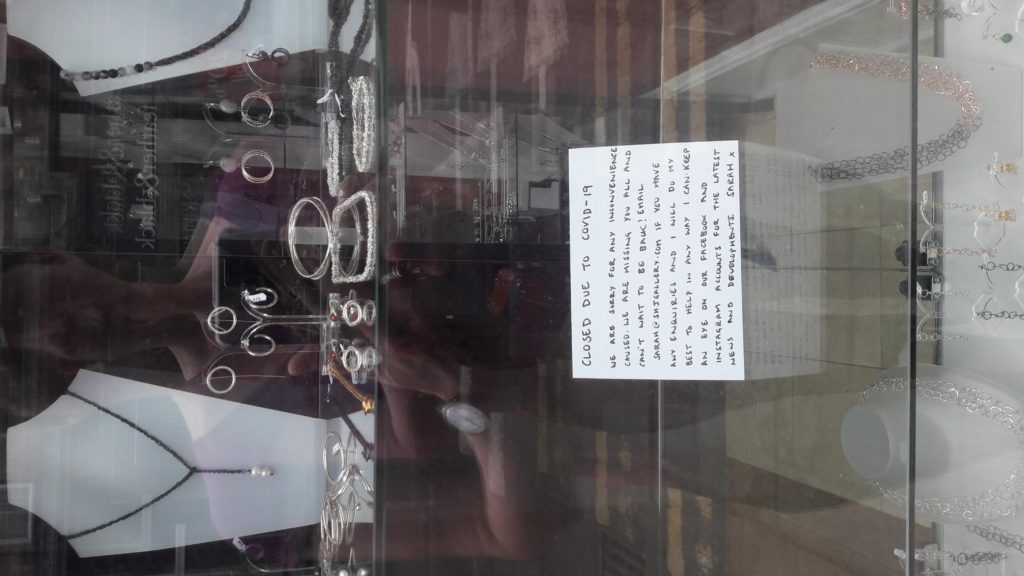

Mary Holmes

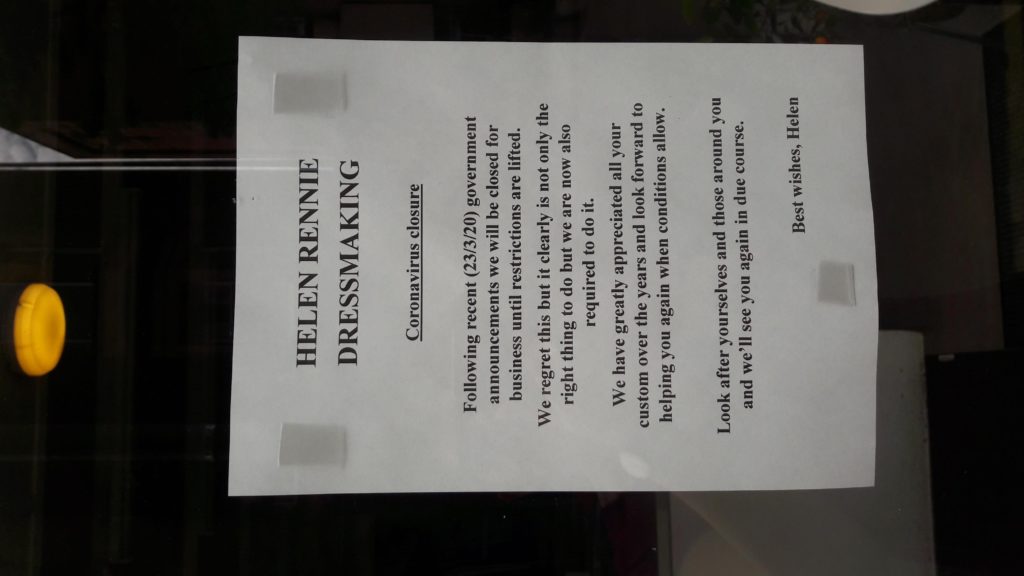

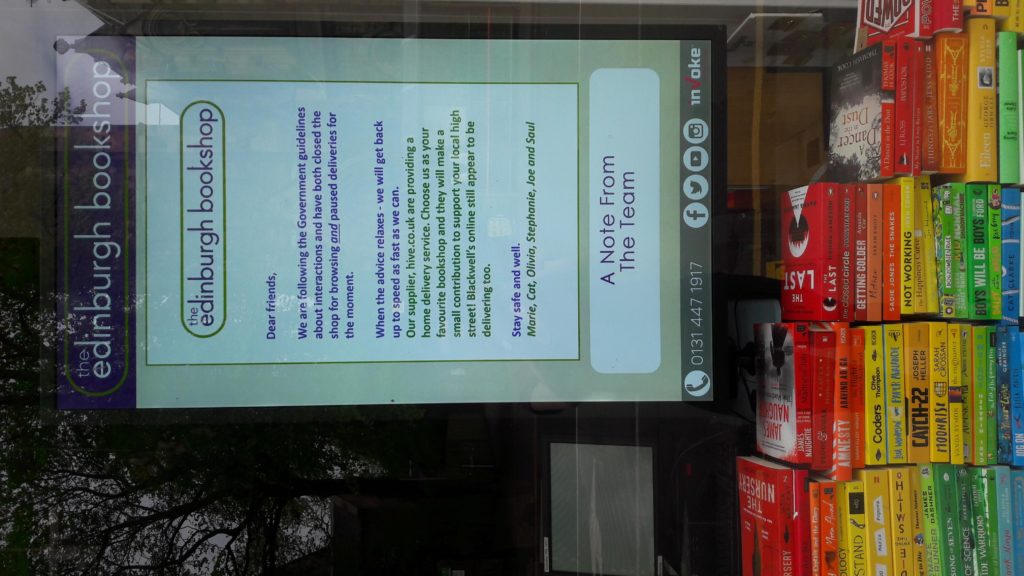

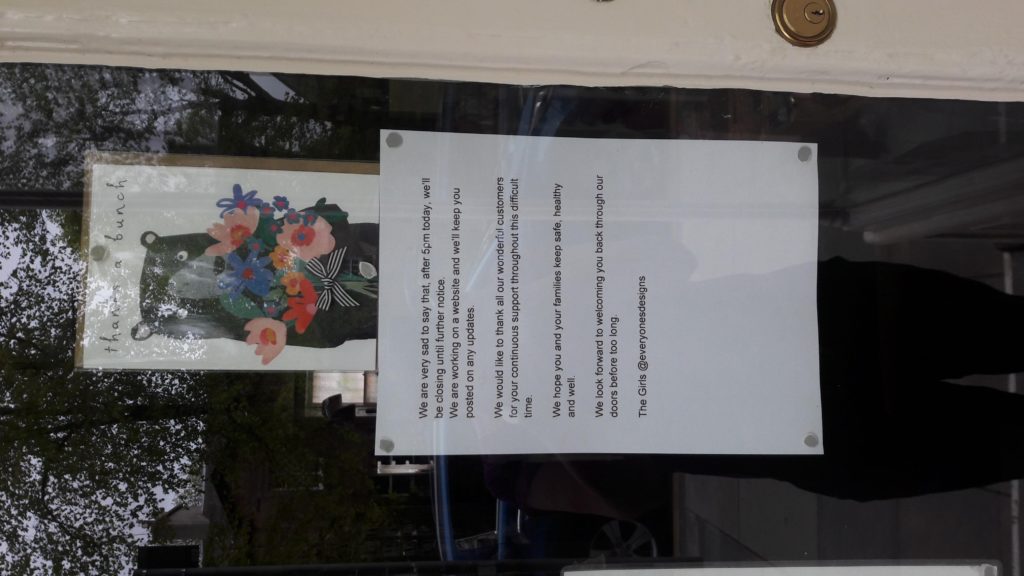

It was a beautiful morning: warm, summery. I decided to go out on my isolated walk early. This meant it was quiet and I was able to stop and take photos of some of the closed notices in the local shops. It gives just a taste of some of the small local businesses affected by Covid 19.

A foreshortened clap was recorded at the Thursday clap last night, 7 May. We had just got going when it was noticed that a neighbour was missing who had been at all the others. No lights in the house but car still outside. A distance conversation took place about this, as there are cases of coronavirus in this small village, in others surrounding, and in the local market town. We don’t know yet. The clap this week was an anxious business.

Chloe MacLean

The mind and body are separate? Oh aye, gid yin Descartes! Try tellin ma body that. It kens what I’m thinkin’ before ma brain consciously understands it. I woke up at 5:45am today, a Sunday, unable tae sleep anymare. This not-sleeping-at-night is becoming an infrequently frequent pattern for me. I was a bit shocked when I woke because yesterday I had a really good day. In the morning I delivered an online group exercise class for ma pals via zoom, and went a long walk tae the meadows. The meadows is absolutely beautiful just now, the cherry blossom trees are in full blossom sprinkling the air with pink petals. The trees make me feel hopeful, I don’t know why, but they do. Maybe it’s a feeling of continuity – that they blossom every year – or that there is always beauty tae be found in horrible times. I also had ma fav dinner last night – fajitas – and a chatted to ma pals on zoom. So it was a good day. I felt calm. Felt content. I felt ‘things are alright’.

But I find maself with under 6 hours of sleep lying wide awake with an anxious buzz across my body. I’m not entirely sure what this buzz wants me to dae, or what its anxious about. It’s a feeling that’s been supressed, but now I feel the anxiety buzzing in my arms and chest, and I canny sleep.

Really, if I was tae think about it, I’ve been thinkin a lot since the pandemic about ma contribution to…life? What am I doing and what can I be doing to help the wellbeing of others? I’ve always kent that time is short, so I’ve always had these thoughts since I was a wee girl tae be honest. But now time feels more pressin. I feel like I have a lot of thoughts in response tae those questions, but, those thoughts are all over the shop. They are flyin all over the shop, fast, so I canny even pick them up to put them in the right order. Ma thoughts are messy, knotted, and difficult to unravel. These thoughts are moving with panic.

There is a storm coming that ma body is bracing itself for. Ma heart canny take the thought of the austerity to come. It’s possible that now I’ve got a gid chance that my bank account will be okay after the pandemic. I’m from a working class background but work as a lecturer now. If there are redundancies to be made at ma work, once the temps and 0hrs staff have been cut, then, I guess, staff that are still on probation like me are easier tae cut. But, even if that was tae happen, I’ve saved as much as I can since starting my first academic post two and a half years ago, so I’d be okay for a bit. I grew up on benefits, I don’t need much money to get by. Without being told I’ve been taught to hold onto money when you get it cause… well, you don’t want the really skint days. And even though the likelihood is that I’ll be economically okay, ma body still feels that panic. Its alert system is on. Ma partner, ma dad, some of ma pals, ma neighbours – things look a lot less certain for them. What’s gonna happen tae the communities like the one I grew up in? Ma heart canny bare it.

These thoughts I feel across ma body as a sickening anxious buzz. So, I am awake at 5:45am trying, with urgency, tae make sense of it all. Maybe tomorrow will be a good day again.