Annette Hay and Mary Holmes

Annette Hay is an archivist and Special Collections librarian at the Auckland Public Library in New Zealand. Mary Holmes is a Professor in the Sociology Department at the University of Edinburgh. In the 1970s they attended Northcote Primary School together.

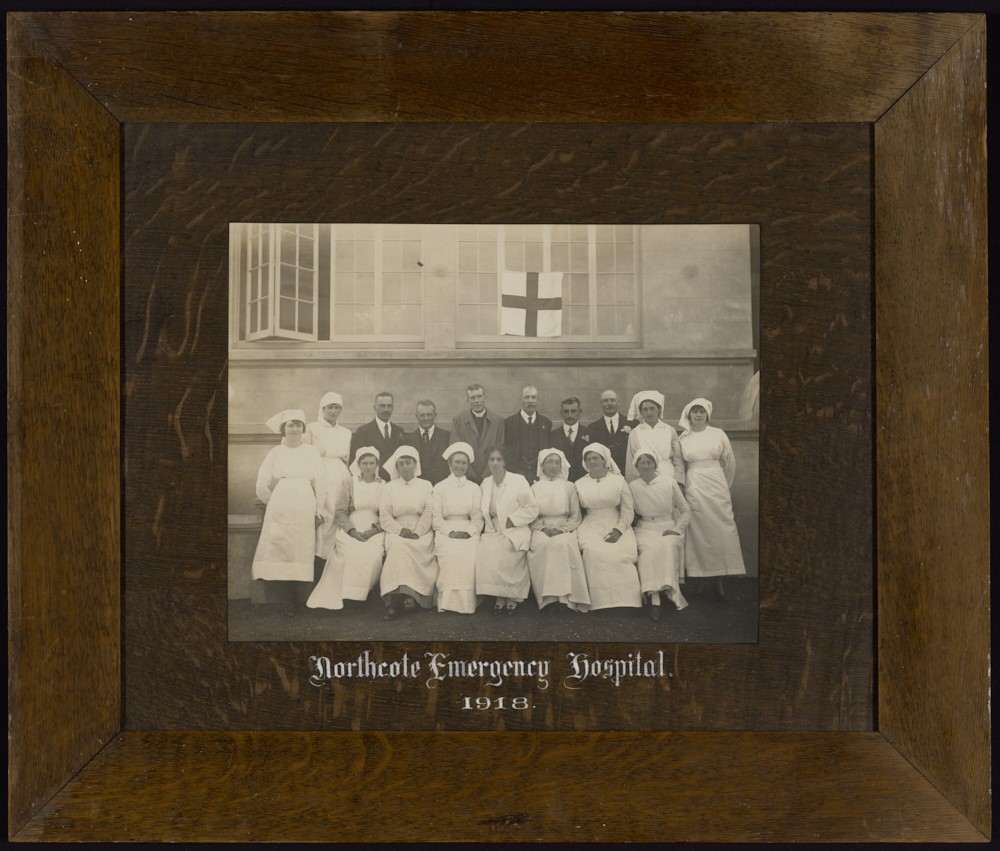

The big grey concrete building was a bit intimidating, but inside the classroom was big and lit up by huge windows. As we started school Annette’s great aunts delighted in telling her that she would be learning in a building that her great-grandfather had died in. Northcote Primary School, had been used as a temporary hospital in the 1918 influenza epidemic. That big grey building had only just been built, and as the flu hit New Zealand that November, it was quickly put into service.

There was a lesser wave of flu that went through the country some months before the bad one hit in late October 2018. The first wave affected the vulnerable: elderly, babies, and those with underlying illnesses. When the second more deadly wave arrived it killed off the healthy younger people, those in the 20 to 40 age group. One of the theories for this was that the more vulnerable who had caught and survived the first wave, had built up antibodies, and those who it hadn’t touched had no defence against the second wave. In just over two months the flu proceeded to kill around 9000 New Zealanders (the country’s population was around 1,150,000), hitting Maori communities particularly hard. There was a special graveyard created for Maori victims of the influenza in Northcote. It was at Awataha, near what is now Akoranga Drive. Some dispossessed Maori lived there in the early twentieth century, given sanctuary on land owned by the Catholic church until they were removed in the 1920s by the church and white settlers eager to more intensively farm and build on the land. Colonialism and wider world events played their part in the tragedies of the epidemic.

It is impossible to separate the story of the 1918 flu and the soldiers of World War I. As the war approached its eventual end on the 11 November, the stories of the epidemic are mixed up with the stories of returning soldiers. Annette’s grandfather, Will Hay, was one of those soldiers. In 1916 Will joined up and served with the New Zealand army in France, he survived gunshot wounds, gas and influenza, but arrived back in New Zealand at the end of 1918 to find that his father had died of the ‘Spanish Flu’ on the 25th of November, aged 51. Scottish born Balfour Hay had been nursed until he died in what became our primary school class room.

The epidemic was another blow to a country reeling from the loss of 18000 New Zealanders in WWI, but Northcote seemed to escape relatively lightly in the flu epidemic, with only 10 deaths in the official records. Like the current Covid 19 crisis, however, the count can be contested. For example, newly-wed Gladys Maxwell was from Northcote but died, aged 26, nursing her husband in a military training camp near Wellington. She was probably not counted in the Northcote toll. Nevertheless, it does seem that Northcote did not fare so badly. Why?

Northcote is a suburb of Auckland, NZ’s largest city, and now it is only 15 minutes drive across the harbour bridge to the city centre. But in 1918 there was no harbour bridge, although regular ferries ran to the city and the population of Northcote had grown to around 1600 – hence the need for a new school building.

Perhaps Northcote’s death toll was relatively low because the narrow piece of water between it and the city helped Northcote isolate? Perhaps it was because it was a village-like and almost semi-rural suburb (known for its strawberry growing) where most people were not wealthy but lived in comfort in houses on reasonable sized plots of land? They had some distance from each other and many grew vegetables. There were not the close together houses and poverty of some of the inner city suburbs that fared much worse. Perhaps however, being able to receive care locally may have made a difference, preventing locals who fell ill from having to go to the overfull Auckland Hospital. Perhaps the care people received in our primary school classrooms was so good that most recovered?

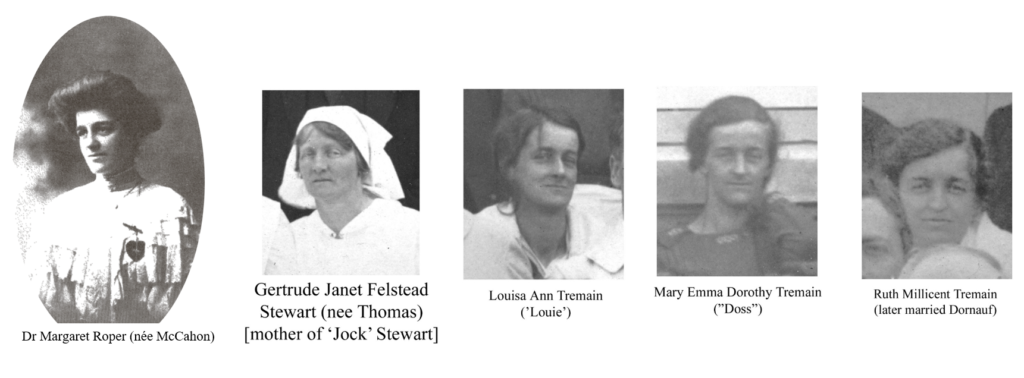

The mayor of neighbouring Birkenhead at the time was certainly reported in the Auckland Star as being of the opinion that without the efforts of staff at the hospital, there would have been many more deaths in the districts. He particularly thanked the Doctor in charge of the hospital, Dr Margaret McCahon (probably the woman in the middle of the front row of the framed photograph above), who later married and became Margaret Roper. Margaret, born in Timaru, in the South Island of New Zealand, was 36 at the time and she came with experience, having been medical inspector of schools for Otago and Southland and Medical Officer at St Helen’s Hospital in Auckland. Margaret was in charge of nurses and volunteers, including some of Annette’s great aunts Ruth, Doss and Louie Tremain and Gertrude Stewart – mother of ‘Jock’ Stewart, a close friend of Mary’s uncle. As it turns out, Margaret McCahon travelled abroad to do her medical training. She graduated MB ChB from the University of Edinburgh in 1908.

Somehow the big grey concrete building seemed haunted but not tainted by that epidemic. But that is just a memory. The building was demolished in the late 1970s, just over 50 years after it was built. The layout of separate classrooms was no longer thought appropriate for new ways of teaching. Of course, the point is not really to remember the building, but to remember the victims of the epidemic and the staff of nurses and volunteers who were under the direction of Margaret McCahon.

Sources

Auckland Star, (1918) ‘The Epidemic. Return to Normal. Northcote and Birkenhead Districts’, 2 December, page 6.

Rice, G. (2005) Black November: The 1918 influenza pandemic in New Zealand. Christchurch: Canterbury University Press.

Verran, D. (2006) ‘The Northcote Fuel Tank Farm to1989’, Speech given to the Birkenhead Historical Society, 13 May.

Wordsworth, J (1985) Women of Northern Wairoa. Orewa: Jane Wordsworth, pp 51 – 54.