Conceptual starting point

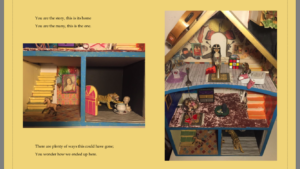

When I was little, I had a Barbie dollhouse that I would spend hours living in vicariously through the characters I created out of dolls and objects. Similarly, when my mother was young she also had a dollhouse she would paint and decorate and use as a vehicle to create and live out narratives. This was a way to both dream the real and escape it, and physically inhabit imaginary spaces in my mind – I had found a way to step into the dollhouse world.

For this project, I want to materialize that same imaginary space through photographs of scenes in the dollhouse and poems that explore certain characters, scenes, and rooms in the dollhouse. I want to explore how narrative is shaped by the individual experiencing the external world and playing with materiality. I want to create narratives around imaginary spaces by questioning the role of each of the characters present in them and imagining what their own thoughts on the space would be, and infuse my own personal memories into it. The lines of what objects belong in a dollhouse are blurred – what is the object’s purpose in the scene? What associations with the object do I personally have, and how do they shape the story I am telling in both words and in images? If I move an object from one room to another, how does meaning shift? What can an imaginary dreamscape reveal about past experiences and how easy is it for the viewer to slip into and relate to the scene?

Ultimately, I also want the collection to feature a film of me stepping into the dollhouse, perhaps with some green screen work, which I will have to research about. I want to find a way to link images and words together that relate to our continuous process of self-creation, and how our internal world merges with and is shaped by the physical space that surrounds us. I plan on potentially recreating some of the dollhouse scenes in the real world, slipping the imaginary dreamscape into the real.

Primary research

I inherited a dollhouse from a friend who was leaving Edinburgh a year and a half ago, Lea. She had spent a few months working on the house, treating it as her own, painting the walls, carpeting the floor. She is the one who gathered most of the objects featured in the photographs. I helped out a bit – I made the Nipple Land background and brought in the fork, and later, broke the ceramic saucer which ends up becoming the All-Seeing Eye. I started taking photographs of it around a year ago, with no particular narrative or story in mind – just objects arranged in an interesting way. When this project brief came along, I knew I wanted to pick up that idea and explore how we shape the narrative of inanimate objects. I did a recent photoshoot with a few ideas in mind about the poems I wanted to write, but again, I let the objects speak and the words follow.

I began by writing one extremely long poem about the dollhouse, with no division in mind, though I knew it would naturally follow from the compartmentalization of the dollhouse itself into its separate rooms and stories. I then divided that one piece of text into four poems, each loosely based around one aspect of the dollhouse and the experience of playing with it. Though I had a narrative in mind, I wanted to leave the images and words open up to the reader’s interpretations, so that they themselves could also be part of this play, infusing the story with their own personal connections and instinctive reactions. Beyond that, I was not even so interested in capturing exactly what the narrative was, but more painting a picture of how it is created, and how it can be changed based on the order one looks at the images or the associations one has with each of the objects.

I reflected on my own experience of playing with a Barbie dollhouse when I was little.

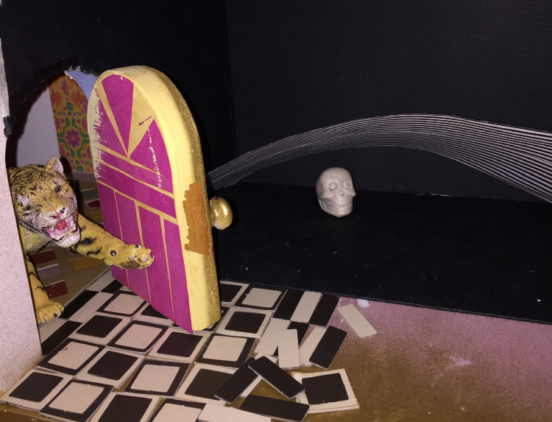

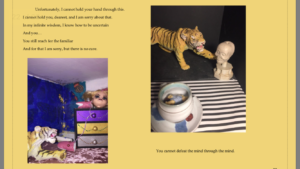

I wanted to link play with Lacan’s ideas of the ‘mirror stage’, in which a child first realizes they are separate from the world. Until seeing themselves in a mirror and recognizing themselves as being that person that is reflected back at them, they experience themselves as being one with reality, and other people, events and objects are all an integral part of them. I based the first poem, ‘Stairwell, 2nd floor – creation’ around this stage in early childhood in which we begin to understand ourselves as separate from the stream of consciousness we experience, and how that conflicts with the way we manipulate the objects that we’re presented with. I imagine that until then, a child that plays takes on the reality that they create, even before the development of language, and that is what I wanted to encapsulate in this first poem: this sense of being God in play, manipulating space before even believing oneself to be separate from it. Play is also a form of performance, and I was interested in capturing the performance of play within and with the dollhouse. Each image was set up so that the objects are acting in a scene, taking on different characteristics depending on their surroundings or what voice I give them. In the photographs on p. 11, the idea was to ‘act out’ the Tiger and the Baby’s imagined first meeting using objects from the dollhouse.

After gathering a few photos, I knew who my characters would be, and I knew that they existed on three separate planes, which are sort of mirrored in the three stories of the dollhouse. Those characters were:

In the dollhouse – Death, Tiger, Baby, Nun, Doll Head, The Eye, Horse, Pipe Machine.

Playing with the dollhouse – The Children.

Beyond the dollhouse -The Knower, the Observer.

In the dollhouse are the objects that, by being of an appropriate size and ending up in my possession, became characters in the dollhouse. They are the objects that when moved and placed next to different pieces of furniture take on a different meaning and shape the narrative. The fork and the dust, both objects left behind that I was simply too lazy to remove, became part of the story. Where does one draw the line in a dollhouse like this of what qualifies as a character and what doesn’t? The teacup, the paintings, and the grave also play a role in bringing about the different scenes, so it can be argued that these should be considered characters as well. The Horse and The Pipe Machine, though mentioned, do not play any significant role in the story. Does that make them less of characters than the Tiger or the Nun?

Perhaps the most emblematic of the objects is the Eye, which appears throughout as a symbol of God and is photographed on p. 27, though it appears in many of the photographs. This object was initially part of the saucer on which the teacup rests, which fell and broke during the filming of ‘Playing with the Dollhouse’. After accidentally dropping the saucer and hearing it break, my friend and fellow artist Alicja Mierzwinska said ‘It’s a sign! There’s been a break in the fortune!’ which then became part of the play. Later, when I was picking up the pieces we had dropped off the ground, I saw this piercing blue eye staring back at me, and I knew I had to redo some shots and incorporate this eye in some significant way.

A broken saucer becomes an Eye

Playing with the dollhouse are the Children, which are played by my friend and me in painted paper masks. I wanted us to represent a sort of timeless playfulness, and wearing masks helped the viewer believe that we could easily be children playing with dolls. In the video we created (which is linked at the end of the book but will also be linked below), I wanted to see what two masked twenty-year-olds could make out of a dollhouse. I had written poems about playfulness, sure, but I wanted to actually experience playing with the dollhouse, and wearing a mask created a sufficient sense of anonymity so that we could abandon our usual roles as people and enter this world we had created as all-powerful, creative Gods who dictate the fate of the objects in front of us. Evidently, the objects are not completely passive in this process; the saucer, when accidentally dropped, becomes an Eye. Initially, I had also planned to do some greenscreen shots of myself walking through the dollhouse and interacting with the characters, but I did not get the chance. If I were to continue this project, I might consider doing this.

ThE ChiLdrEn, stills from ‘Playing with the Dollhouse’, Blades, 2021

Beyond the dollhouse are the more metaphysical, intangible characters referenced throughout the poems. This is the Observer, which is embodied by the Children, but also possibly by the Tiger depending on how you interpret the story; and the Knower, which steps in in the last poem to sort of humble the Tiger/ the Observer. One of the possible interpretations of this collection is of the dollhouse as the Tiger’s purgatory; that his body died but his brain is processing his life in this bizarre form. I knew the Tiger initially appears scary, and that is an instinct a child might have in play, but as the narrative is created, the Tiger learns acceptance and we learn his anger and fear are justified by the experiences he’s had.

The poems, particularly ‘the kitchen – the knower’ are infused with some ideas from the eastern philosophy of Advaita Vedanta, which is a non-dualistic tradition that considers each individual soul (Attman) is identical to Brahman, an unchanging, universal consciousness that underlies all things. I thought this was an interesting idea to contrast with Lacan’s philosophy; the realization that what we see in the mirror is separate from ourselves and each other, one that is essential to our social development, actually distracts us from the truth that we are the source of our own creation. Someone once told me a story that when you die, there is a small chance your mind might get stuck in between dimensions, and because your sense of time would be skewed and caught in a loop, you could experience years of nothingness: be a true mind without a body. That idea terrified me, but it also inspired a lot of this project. What sort of narrative would this toy tiger have had he died and his brain been caught in a limbo of his own creation?

This was a philosophical experiment in child’s play, an exploration of existential topics within a childlike framework.

Secondary research

‘Here is Elsewhere’, a film made by Sarah Wood at the beginning of lockdown, illustrates a world of people becoming ‘nomads of the imagination’, our minds travelling and reaching out to one another, across time and space, while we’re apart. Storytelling helps us make sense of that which can feel impossible, by helping us visualize places different from the ones we inhabit. It connects to my collection which captures a story within a dollhouse within a bedroom in lockdown. It reminds us how taking time to pause, for those who could afford to, involved for many remembering a child self and the way we used to understand the world, and the things we used to love.

I began reading Dante’s ‘Inferno’ last year with a friend, and the symbolic imagery of a mortals trip through hell influenced my project with the dollhouse massively. There are multiple narratives going on across the poems, much like in Inferno, a pilgrim encounters many people and places in hell and gets to know their stories. The pilgrim is in a state of limbo, not fully dead and not fully alive, much like what I imagined The Tiger in my story to be, and the dollhouse be his souls’ version of the circles of hell.

Lacan’s mirror stage, which happens between 6-18 months, details a moment in which a child first realizes they are separate from the world. Until seeing themselves in a mirror and recognizing themselves as being that person that is reflected back at them, they experience themselves as being one with reality, and other people, events and objects are all an integral part of them. This was important in the dollhouse because at the beginning, a child feels like imagination is reality, because they have no concept of themselves – that is the kind of imaginative headspace I wanted the poems and images to emulate.

I read about the eastern philosophy of Advaita Vedanta in ‘Journey from many to one’, which details some teachings of the non-dual tradition. According to this tradition, Brahman, the eternal truth, is beyond this world of time, space and causation.

‘As long as this world seems real to us, we live in a world of pairs of opposites. Everything we know in this world belongs of a pair of opposites.’

I tried to tap into a mindset without opposites, of all-pervading consciousness, just as we are before recognizing ourselves in the mirror. As gods, unconscious creators of reality, now deliberate performers of time and space.

Villem Tulser’s writes about how humanity contradict the second law of thermodynamics, which tells us at that everything in nature has the tendency to be forgotten. Humans, in contrast to all known creatures, relay information across generations not only through genetics, but also through the passing on of learned information. This is cultural memory. ‘The dollhouse’ is written from a specific point of view, but it illustrates a narrative about the very human process of creating and searching for meaning, that can hopefully be understood differently over time, as one becomes more familiar with the language of the creator.

I researched the history of dollhouses and found an article, ‘Dollhouses Weren’t Invented for Play’, which detailed how dollhouses began and the writer’s own experience growing up playing with dolls.

‘As a character in my dollhouse—my mother had sewn a doll with long hair and glasses that resembled me—I could be an orphan sleeping in a cot built from a ring box. Or a teenager lying with a boyfriend on a tiny bearskin rug, drinking wine from a mini bottle and devouring a polymer chocolate cake the size of a dime. When I arranged tiny brass beds or slid a plastic roast chicken in the oven, I entered another universe.

And yet, at the same time, I also ventured more deeply inside myself.’

Historically, the dollhouse began as a symbol of wealth and a way to introduce young women to domestic roles, which seems to contradict the idea that dollhouses are spaces of emotion, imagination, and freedom.