Lammasmägi hill, Kunda.

Lammasmägi (Sheep hill) is shown with the red marker in the two maps below.

Lammasmägi hill was the first discovered site (in the 19th century) that provided extensive finds of Mesolithic inhabitance in Estonia. There were people living in this place since the Stone Age. It is the most well known archaeological site in Estonia. And is known of by most European archaeologists because the Mesolithic Kunda Culture was named after it. The Mesolithic Kunda Culture was a culture of hunter-gatherers from the Baltic forests stretching into eastern Russia dating from 8500-5000BC. Lammasmägi is the place where “the oldest known traces of human activity on the Baltic Klint (from about 9000 years BP) were discovered” (https://www.looduskalender.ee/klint/eng/16.html). The oldest known human settlement in the whole of Estonia is the Pulli settlement of the Kunda Culture which is on the right bank of Pärnu river, which is in the very south of the country.

In ancient times the area of Kunda was a lake. Lammasmägi hill was an island in this lake. This site was inhabited from the time of the ancient lake, through it’s change into bogland, with the Kunda river being the left trace.

The Kunda River runs past this settlement on it’s right side and continues all the way to the coast. This river is the river that I encountered while finding my first batch of clay in Estonia, from next to the Kunda quarry. This is the river that I was considering siting the sculpture in, submerging the bottom vessel in, if digging the work back into the ground didn’t feel right or didn’t quite work.

Below is some writing I have been working on, mainly for my dissertation describing the process of finding the clay and highlighting the special feeling this river seemed to carry, even when I had no idea of it’s history.

“As I followed the path I was once again engulfed by tree cover. I came to a swell in the river, the light was shining through the trees and I could see how clear the water was. Listening to the river on my right and hearing the thundering trucks passing a short distance to my left. I continued to follow the path as it changed into deer tracks and became more boggy. The deer track led to the edge of the river, on the opposite side of the river there was a worn opening in the trees and the path continued. The animals were passing through the water as the forest on my side of the river became too dense. The water was too cold and too deep for me to cross alone. It was becoming clear that this river was not leading me towards the clay but on another journey. I sat by the water and ate my lunch. There was something magnificent about this river. It was so strong and beautiful running right through the heart, surrounded by the dust and grit of industry.”

I know the specific calm outlet where I would leave the work.

I was listening to Samantha Clark’s spoken word that accompanied her short films. She talked of water as being this ancient material, constantly in a cycle within our environment on earth, water is old, changing form and moving always but it is old. I have been thinking about how some materials gather history as time moves around them. They are able to have a physical constance. As time moves and lives unfold and collapse some things stay and witness these passings. Before I was seeing this material as geology, as rock, silt, clay. But it is not only rocks. As geology can’t happen without water. Water exists and withstands just as much.

My main reason for considering the river from the start was because of the sand. I collected sand to place in the top vessel to fall through into the form below. This sand I took from the beach at Kunda bay. If it was to be put into the river it would make it’s way back to where it came from. And the water would similarly wash, break down, carry the clay vessels. I believe vessels belong with water. The bottom vessel, while following the undulating profile of the land at Paldiski, has just so happened to find itself as a boat-like form, with the line of the profile creating a keel.

I have recently visited some sacred springs of Estonia at Saula and have been reading of Estonian people’s relationship to sacred springs. Once again there seems to be this interaction between geology, rocks, earth, holding, and water.

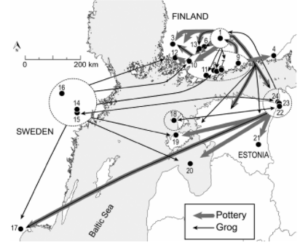

The Baltic sea has always been a place of exchange, of trade, not a barrier but a connection. I have been reading of the Neolithic Corded Ware Culture and Narva Culture. There were extensive movements between Estonia, Finland and Sweden. These movements were not only of pottery but also very often of young female artisans, who would learn their craft in their homeland and then relocate with marriages. Movement of grog provides evidence of this. Through analysis it has been found that when these women moved to a new place they took with them crushed sherds of pottery from their homeland, from the generations before them. I find this to be an incredibly beautiful tradition. Allowing for their work to carry time upon time. Working containing the work of those before is again carried into new work and so on and so on.

Map detailing networks from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338514138_Tracing_grog_and_pots_to_reveal_neolithic_Corded_Ware_Culture_contacts_in_the_Baltic_Sea_region_SEM-EDS_PIXE>

In this sense there should be no fear of breaking work and allowing it to be part of the landscape because this is what allows it to continue. When I was learning from Doug Fitch and Hannah McAndrew they would regularly abandon, throw pots over the other side of dykes if they were no good, even with small flaws, as did many generations of potters before them throughout Britain, as well as elsewhere of course throughout Asia.

“fragility does not mean ephemerality; what we know of ancient civilizations is often based largely on the persistence of broken bits of clay.” (Koplos 1998)

To place my work in the Kunda River and leave it there, the broken vessels would eventually become grog and flow into the sea. Some sherds would become stuck in the surrounding land and add to the mass of our traces and others would float back into the floor of the ocean. Finding their way back to the environment where during the Cambrian period life existed. And where during the Neolithic period people travelled over to establish the civilisations we have now.

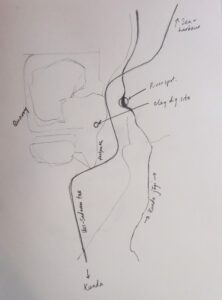

Kunda the town is formed around the processing factories for the mined resources. The river can be seen running along it’s right side and down past the blue exposed veins of the quarry.

Here is a map to illustrate the proximity of the place where I dug the clay and the beautiful swell of the Kunda river.