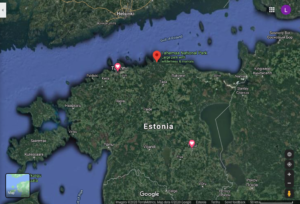

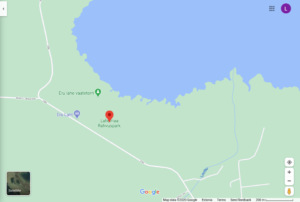

Eru Laht, Vihasoo, Lahemaa National Park. Clay finding. 24th October 2020.

Lahemaa National Park is 70km East of Tallinn. Lahemaa is one of Europe’s most important conservation areas where moose, bears, lynxes and boars live. It is massive, dense and wild. I travelled by car with two of my flatmates, Oli and Pierre. We went to get out of the city and catch the autumn colours but I brought my shovel and my backpack.

We parked and walked into this marsh area, heading for the tall bird hide. I was doubtful that the marshy bay would result in much clean clay underfoot, expecting mostly sandy mud.

As soon as we entered the marsh areas I began looking at the trenches that were sectioning off many areas. In them I felt I could see the possibility of clay underneath a foot or so of top soil. This lighter layer. I reached down over the edge of one section and pinched the earth with my fingers. It was soft and malleable, it had the immediate plasticity of fresh clay.

I was surprised at myself of how quickly I recognised the slight sheen in the mud. There is a certain silky texture, even when in a completely rough gritty state that identifies the clay. I was instantly excited by the thought of knowing there was clay once again under my feet.

We went up the bird hide first. As it was clear that we would have to climb over the trenches and electric fence in order to get to where the clay was easier to dig.

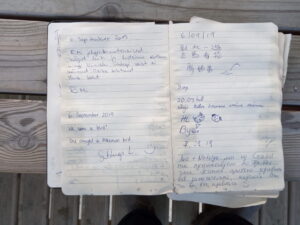

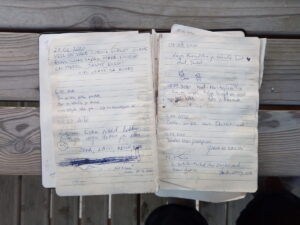

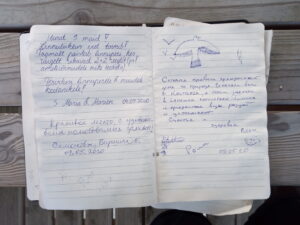

In the top of the hide there was a bird spotters record book for all visitors to leave notes. There were so many different messages left, in many languages over several years. I left one too. A small poem really, dated. About finding the clay, and some sentences that Oli was saying while I was writing, although he didn’t realise I was instantly recording his words. We all signed the bottom. I didn’t take a photograph of the poem, I felt it was best to be left in that place, for other people who also travelled to that place to read. It was written of the present moment and so I left it there.

Here are some photographs of others messages and drawings.

The book was wet. It was a wonder it had held together and survived so long. It was kept in a plastic case but the water had clearly leaked in. This day was much colder than my digging at Kunda, gloves were a must. It seemed to affect the whole experience of digging. Somehow the smell of the soil was stronger. Maybe because of so much bird life living there too.

Coming down from the bird hide we found a trench to jump, luckily the electric fence wasn’t turned on. It was the only way to get to the good clay. You couldn’t think about it too much. If you hesitated then you wouldn’t make it. It was also too wide and too deep to land completely on your feet, your hands touched the grass and earth too as you landed on the other side.

I found a spot and started digging. The others amused themselves by climbing up very tall trees.

This clay is very different to that at Kunda. It is much lighter and brown in colour as well as texture. It was not as even, some parts being speckled with stains of rusty iron, some more blue-ish, others very sandy. It is definitely clay but the variations within this one area were large and near impossible to get a pure sample.

The plasticity of the clay seems low, mainly due to the fact of there being such a high sand content. The speckle of iron and variation in colour could make for a very interesting body or addition to glaze. However, I suspect that in order to make strong forms it may be necessary to mix this clay with another body.

I stopped digging at around the same weight as before. 10-12kg, maybe slightly more. This is the limit of what I can carry on my back, and probably too the limit of what my backpack can support.

In jumping over the trenches weightless it was not so difficult. However, on the way back we had the weight of the clay. Oli jumped over first, now on the far side of the trench. I handed the bag to Pierre. He preferred to hand it to Oli because of the weight to catch but Oli insisted on him throwing it over, it was slightly too far to hand. Pierre gradually swung the rucksack back and forth to build up a swinging momentum and then released and threw it to Oli. Oli reached and caught it just right with the weight throwing him back a little with the clay.

This act, or series of movements, is something I am considering incorporating into the sculpture that will be made from the clay.

If I had been alone I would have had to split the clay in two. Throw it over first before me. And then myself jump. However in company a pendulum exchange of the material happened. It was much less an intensely individual experience as I felt at Kunda. To be alone and relying on yourself, without the help of others. In this way it would be fitting to have the others actions as part of the finished work, as in some way they are also now within the clay collected.

I have always found the thin spindles of silver birch all over Estonia very enchanting. They are so white against the darkness of the woods, and the shine that they catch in the sun is beautiful. I have been working over in my mind for a long time how to portray this in sculpture, in ceramics.

There was a large group of Valgepõsk-lagle. They had striking white faces in contrast to a purely black neck.

There was vihasoo künnapuu. The ‘angry swamp tree’. The third largest plum tree in Estonia.

From here we went onto Viru bog.

The bogs of Estonia are one of the country’s most distinctive natural habitats. There is a board walk which allows you to walk the 9km trail through the peaty landscape. The colours are quite unreal, so distinctive in their reds. Most of the trees are only able to grow to a small height because of the climate and over-saturation of water. The first image below shows one large area of the bog which was extensively damaged by peat mining. Throughout many attempts to reconstruct the delicate eco-system of the bog it has not proved possible and this area remains very different to the preserved parts of the bog. In the preserved areas there are deep dark peat water pools, which are reservoirs as they collect purely rain water and are stagnant. The algae in these pools purifies the water. These pools take many many years to form, as they are literally puddles that have gradually eroded and grown. There are some interesting lifeforms that survive in the barren environment of the bog. One of which being small red carnivorous plants.

The time span it takes for these peat pools to form may provide some interesting further research to impact my vessel making.

The whole day is one that has provided lots of information to process that will form the work made from the found material. This will happen as I unpack the clay and wedge it into one.

Having left Tallinn in the morning, we returned in the evening. Very hungry having not eaten since leaving the city. The day ended with a large dinner, finished with crepes made by Pierre.