From Peri-Tethys to Paratethys – Basin restriction and anoxia in central Eurasia linked to volcanic belts in Iran (and an interview of Dr Annique van der Boon)

Dr Annique Van Der Boon is a respected scientist and content creator who has a wide European research portfolio as she worked at various EU institutions, been on multiple field excursions around Europe and studied at the University of Utrecht. She currently works at the Department of Earth, Ocean and Ecological Sciences, University of Liverpool.

From Peri-Tethys to Paratethys – Basin restriction and anoxia in central Eurasia linked to volcanic belts in Iran

Annique’s lecture focused on ancient sea sediments and their connection to anoxia, global volcanism and the evolution of life linked to extinction. She went on a series of field excursions spanning the Eurasian continent! She visited Germany, Russia and Iran. In Germany and Russia she looked at ancient sediments from the Peri-Tethys to the Paratethys oceans spanning over 10 million years. Her work provided a nice insight into the geological evolution of the European continent.

The initial theory that prompted Annique on her journey arose due to unexplained gaps in the geological record. It was known before that the now gone ocean underwent several cycles of mass die off due to basin restriction and anoxia. The main question remained: What caused the anoxia?

The changing basin is explained by the shifting of the Arabian plate and African plate leading to more enclosed basins. This changed ocean circulation, preventing a better distribution of oxygen. This lead to a change in the sea level showing evidence for ocean-continental transition. This doesn’t explain the complete picture. A lot more factors are needed for ocean scale mass deaths. These events are usually connected to bigger events such as volcanic eruptions or global temperature change. Leading to two questions: What were the large changes causing the anoxia and what was the source of these changes?

In order to find out the source of the anoxia, Annique travelled across the entire continent until reaching Iran. She collected samples in Germany, Romania, Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Russia, Iran. She talked about her amazing journey in the interview bellow.

She studied the areas mentioned in the following manner: Paleomagnetic measurements, Radiometric dating and geochemical measurements in the lab with XRF and ICP methods. All these techniques required sample collections on location.

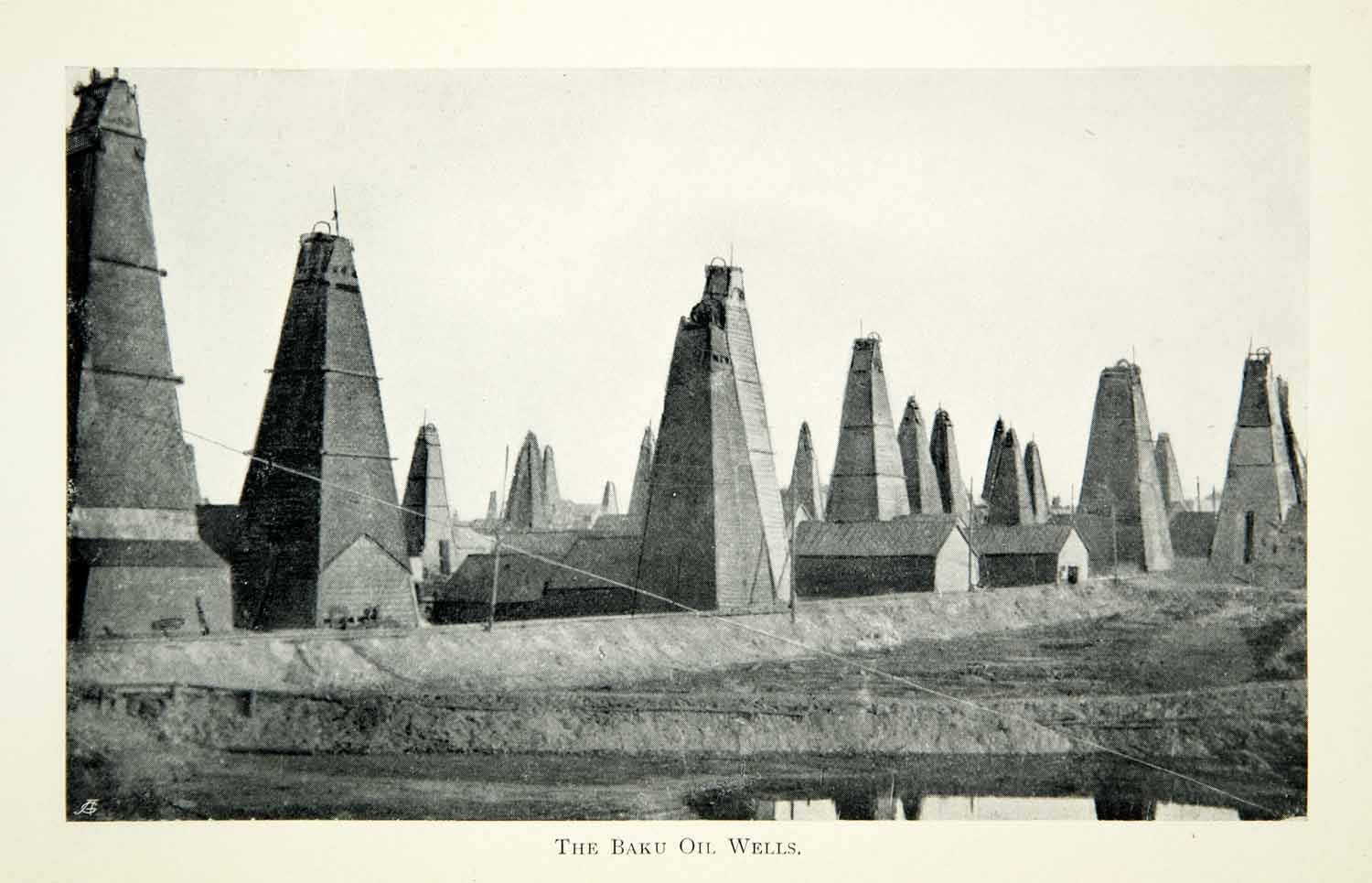

Iran is the country of earthquakes and past heavy volcanism. The country is located in a region where continental plates meet. Millions of years ago the entire region was a giant sea, part of the Paratethys. Her field trip in the region examined all the possible evidence for heavy volcanism.

Annique suspects underwater eruptions lead to the acidification of the past ocean as the volcanoes acted as a giant CO2 pump. This in turn caused the mass die off. She explained to us the sequence of events according to her assessment: Heavy volcanism as part of a subduction volcanic arc and a massive scale eruption. First mass die off occurs. Arabia-Eurasia continental collision follows where there are no mass die offs. The anoxia begins again when the larger basin of the Paratethys ocean closes off. This timeline could explain the large amount of anoxic layers in the sediments and the large oil fields.

You can read more about Annique’s work here.

Fossils across Europe! – Fossil, sediment successions from the Paratethys ocean

Interview with Dr Annique Van Der Boon

After the lecture, I emailed Annique and she was kind enough to give me an interview and photographs. We discussed how she got into the subject of geology, at which universities she worked at, what were the differences between Dutch and British universities and her field trips to Germany and Russia. It turned out she does a lot of university outreach and produced a series of educational videos. She was kind enough to provide me with photographs from some of her outreach work. Onto the interview:

Would you be able to give a quick summary of your scientific career? What made you take up the subject of geology?

I started out studying physics, but after a year, I found that I did not like it so much. I had no idea what to do and thought of becoming a veterinarian. However, in the Netherlands there is a lottery system for the limited number of places, and I was unlucky. As a back up, I had signed up for Earth Sciences but I had never visited any open days and did not really know what this study was about. When I started, I found that I really liked it, and finished my BSc and MSc at Utrecht University. I especially enjoyed fieldwork, and so during my studies I chose subjects for my theses that had fieldwork. Paleomagnetism seemed to have the best opportunities for fieldwork, so I continued down that path, and also did a PhD at the paleomagnetic laboratory.

Do you travel a lot as part of your research? What was the most interesting place you have visited?

The best part is all the fieldwork and traveling!

I have so far spent about 10% of my scientific career away on fieldwork, and I’m doing my best to make that more. I liked most of the countries that I have visited, as they are so different, so each place has their own special thing. Some field trips have been with close friends, where you have a lot of fun. Other places have astonishing geology, or are very difficult to get to, which makes it more special when you finally manage to go there.

Travelling around the world – taking samples in the Ammer section in Germany

What was the most interesting memory from your trek of the continent? Travelling from Germany to Russia to see sediments must have been a wonderful experience!

Germany was a really great field trip because I went with a good friend, and we had so much fun sampling the amazing Ammer section, with our little inflatable boat. Russia was really special because it is a place that is a bit harder to get to. The Russians we met and worked with are very kind and have a great sense of humour. Plus we had this inflatable boat which we used to go down the Belaya (which means ‘white’) river, with our captain Sergey Popov, who is one of the most knowledgeable people on the Paratethys and the Maikop Group, so it was really cool to work with such a legendary scientist. Iran was also great, the quality and extent of the outcrops is superb, and the geology is relatively unexplored, so you really feel like an explorer going there. I recently went on fieldwork to Canada for the project that I am working on at the University of Liverpool, where we were dropped in the bush with a helicopter, so that was really cool too!

(Unfortunately I did not do a trek from Germany to Russia, these were separate field trips, but it is one of my dreams to fully explore the former Paratethys. Maybe one day…)

#licencetodrill – Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition in London, on the right is Dr. Anouk Beniest, from the Free University of Amsterdam

From your Twitter I noticed you do a lot of GeoSciences outreach. What type of outreach work do you do? What do you think: Is the field of geology doing enough to reach out to the public?

I only recently got into outreach, as our group had a stand at the Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition last July, and I was the lead on that. It was a great experience, where we had people explore what it’s like to be a paleomagnetist. We took our visitors on a ‘fieldtrip’ which involved getting them into a high-visibility vest and a hardhat (safety first!). After the samples were ‘collected’, visitors could measure samples on our custom-built magnetometer, to determine the polarity of the samples. We had borrowed a large magnetic globe from the University of Bremen, which simulated a magnetic polarity reversal. Our final experiment was ‘rock or choc’, where people could try to find out if pebbles were real rocks, or made of chocolate, by measuring the magnetic susceptibility. For me, outreach was very rewarding, as people get really excited to hear about your research. Things that are not so special anymore to geologists are usually quite amazing to other people, so I found it very motivating to see people get excited about rocks and the science that we do. In the UK, scientists seem to be a lot more involved in outreach when compared to the Netherlands, and I think this is a really good thing. After all, a lot of research is funded from taxes, so it is good to keep people up to date on progress made in science.

I also learned quite a bit myself while designing the stand and outreach materials: Ten things you might not know about the Earth’s magnetic field.

From your LinkedIn I noticed that you went to a Dutch university, the Utrecht University. What are the differences and similarities between Dutch and British universities? What is the teaching and learning culture like?

There is quite a bit of difference between the Netherlands and the UK. Of course I can only compare Utrecht University and the University of Liverpool, as these are the only places that I have worked. In general, teaching in the Netherlands is more focused on independance, and students really have to take initiative, where in the UK they are guided a bit more. A big difference is that in the Netherlands, PhD students are employees and get paid a good salary (with pensions etc.), while in the UK they are students. The UK seems to focus more on inclusivity and diversity, which I think is a good thing. However, bureaucracy here is really intense compared to the Netherlands.

Follow Dr Annique Van Der Boon on Twitter for amazing science content!

She has a nifty video site as well.

The importance of EU wide and international geology cooperation

My main take away from Anniques brilliant lecture was the importance of EU and Europe wide cooperation. She couldn’t travel to Germany or Russia without the help of those countries. In these modern times it is very important to work together. A lot of great papers couldn’t have happened without the background of international logistics, paper pushing by bureaucrats and human to human connections. This lecture wouldn’t have happened without an amazing array of international people coming together and sharing knowledge. Science cannot survive without openness and outreach. Scientific data is shared, understood, revaluated and appreciated together. People like Florian, Simon, Steve, Mikael are the lifeblood of the university.

We know things because they helped us to understand. Post Brexit, the university should not give up on being a forward looking, international university. There are always those who seek to divide, to cast ignorance and burn bridges. But there are always people who are willing to build a connection across the water as well.

Russia-EU summit in 2014

Recent comments