Lecture 6: Called to Peace

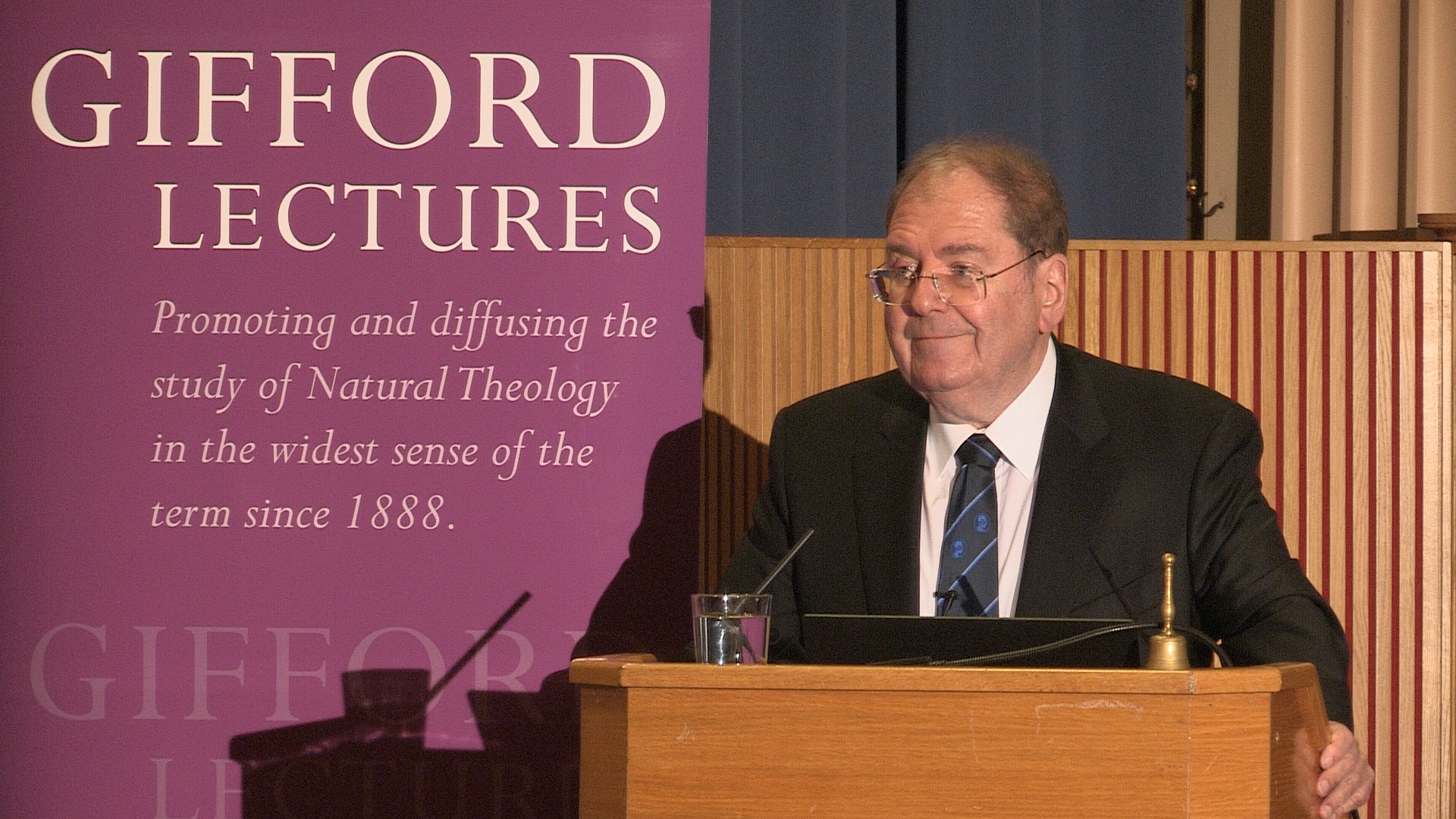

Senior Professor Michael Welker gave the final lecture of his Gifford Lectures earlier this evening. The video of Welker’s lecture is embedded below (followed by a short summary) for those who were unable to attend in person, or for those who’d like to watch it again. An audio only version is available at the end of this post. In order to further facilitate discussion. Craig Meek will offer his initial reflections on the lecture. Meek is currently a PhD candidate in Systematic Theology here at the University of Edinburgh. We’d like to reiterate that we warmly welcome anyone wishing to engage with Welker’s lectures to contribute their comments and questions below.

In the beginning of his lecture Welker noted that “many people understand ‘peace’ to mean primarily the absence of war,” but he went on to note that “opinions on how best to attain and secure peace can vary widely.” Along these lines he drew attention to the significant amounts of money currently being spent on arms expenditures around the world today noting that according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute there is “a disturbingly intense arms race currently underway throughout the world.” He went on to affirm the lamentations of Gerd Müller who stated, “if we could redirect even a quarter of military expenditures toward developmental cooperation, we could put a stop to hunger, death [i.e. death caused by severe conditions of distress and disaster], and poverty, as well as to the miseries of refugees worldwide.”

Here Welker began the first major section of his lecture dealing with Immanuel Kant’s On Eternal Peace in contrast with Vegetius and his influential motto “if you want peace, prepare for war.” As Welker described, Kant was not some sort of “rigid pacifist” but he challenged the assumption that peace “can be attained solely by means of maximum armament, a perpetually expanding production of heavy weaponry, and the concomitant development and expansion of organized military powers.” Peace cannot simply be equated with “ceasefire.” Rather than solely focusing on the power of weapons and violence Kant emphasized the role of justice and politics. As Welker described Kant’s position, “only conceptual and political efforts subordinated to the idea and praxis of the rule of law and justice can promote peace” and he went on to state that “Kant presents an ethical-moral, political, and legal process of inculcation in which the multimodal spirit of peace can unfold.” Welker then went on to speak about how Kant can be seen to be the “conceptual precursor of the charter of the United nations of October 24, 1945” and he noted how these ideas remain relevant today. Welker summarized Kant’s maxims thus:

- If you want peace, then promote respect for the truth and a commitment to communication that seeks the truth. This requirement is inherent in Kant’s demands that actions relating to the rights of others be compatible with publicity.

- If you want peace, then appreciate and promote your own freedom and that of others.

- If you want peace, then ensure justice.

He then went on to state that “the extent to which the multimodal spirit of peace is interwoven in a variety of ways with the multimodal spirit of justice, freedom, and truth becomes quite clear in these considerations.”

At this point Welker moved on to his second major section of the lecture asking “how are people to be persuaded to withdraw their loyalty from the politics of a spiraling arms race? How can one ignite a passionate interest in them for ‘eternal peace’? Which sources might nourish such commitment and courage for eternal peace?” In order to begin to give an answer to these questions Welker went on to speak about “peace as an internally human and civilizational disposition” and he did so, first, in conversation with Alfred North Whitehead. As he stated, “Whitehead defines the spirit of peace as ‘a broadening of feeling’ that generates a remarkable expansion of self, of the person, or of the entity that focuses on peace” and after having discussed Whitehead’s position in more detail Welker went on to note that “although this vision of peace as a creative process that transcends primary interests in simple self-relationships and self-preservation may seem rather vague and effusive, it does nonetheless offer a perspective from which to discern insufficient or inadequate notions of peace.” Some of the inadequate conceptions of peace in this vein are notions that mistake peace simply for tranquility, order, or security. As he went on to explain, “even those who perpetrate extraordinarily repressive or even terroristic circumstances can boast about the regnance of tranquility, order, and security within their own spheres of influence.”

Welker then turned to briefly engage with Augustine’s doctrine of peace. According to Welker Augustine “focused on the idea of social order that ensures calm and justice” and he associated “peace with ‘undisturbed order’ in which justice reigns” where God is understood to be “the ‘governor’ of this order.” Welker critiqued Augustine at this point saying that “this view in its own turn merely obscures the difficulties accompanying any linking of a sustainable understanding of peace with a persuasive program for the realization of justice.” A more realistic description of the divine Spirit as it relates to the human spirit is necessary to move beyond this vague conception and Welker went on to argue that Whitehead helps here and he went on to briefly discussed how love relates to peace.

In the third section of his lecture Welker focused on “benevolence toward humankind and shared joy” as they relate to “true inner peace.” He started off by speaking about love as a “free creative self-limitation and self-withdrawal on behalf of others” and he went on to state that “through giving and receiving this love, a person acquires even in this life a portion of the ‘eternal life’ that points beyond natural-earthly life circumstances.”

He then moved on to talk about the significance of cooperation and collaboration in our evolutionary history as they relate to inner peace, sacrifice, and love in conversation with Martha Nussbaum, Martin Novak, Sarah Coakley, and Sigmund Brandt. He then spent some time talking about our understanding of feelings and emotion as they help us better understand the various forms of love. As he stated, “distinguishing between hot, warm, cool, and cold emotions can help impose order on the world of feelings” and that it is “only ‘warm’ love of the sort we both give and experience within the intimate sphere of parental love that can be associated with ‘inner peace.’” He went on to explain further that “the grand magical power that turns love into a universal power of both internal and external peace resides beyond the powers of warm love within what one might call the cool and calm love of benevolence toward humankind that wishes only good and never ill to one’s fellow human beings.” He then moved on to talk about the importance of recognizing the polyphonic forms of joy. As he stated, “in this context, it is important that joy be acknowledged and appreciated not only in its more overt, effusive, jubilant forms but also in its quiet or even cool, self-forgetful manifestations.”

Welker next spoke about “the life experiences and feelings of people at advanced ages, including those at extremely advanced ages accompanied by dramatically increasing fragility” as they approach death. He then inquired into what forms of peace they were able to experience (and he briefly discussed how their experience compares and contrasts to the experience of young children). As he stated, “even amid diminishing physical and spiritual-intellectual powers, gratitude and hope generate feelings of strength accompanied by joy.” Welker went on to argue that “this experience of peace resides securely and reliably within the warm love toward others in one’s immediate sphere as well as in the cool and calm love toward others quite beyond any ethos associated with intimate spheres, and through precisely this engagement that same experience acquires a beneficent radiance and resonance even at the very boundaries of life’s natural energies.”

At this point Welker began to conclude this lecture and his series as a whole. He reminded us that he has tried “to develop a natural theology of the human and divine spirit.” After having acknowledged the finitude and frailty of humanity along with our susceptibility to seduction, self-endangerment, aggression, and destructive inclinations he reminded us that he has been inquiring into “what powers of the human and divine spirit might counter this discouraging state of affairs.” He has sought to develop a “realistic” natural theology that can help us better understand how human beings can be said to be in the image of God. He focused his answer around the multimodal spirits of justice, freedom, truth, and peace.

As he succinctly stated in regard to justice, “people filled by the multimodal spirit of justice become capable of engaging on behalf of justice in both word and deed in a world characterized by radically inequitable and unjust life circumstances. Precisely thus, such people are indeed called and shaped in the image of God.”

In regards to freedom he stated that human beings are “shaped in the image of God when the multimodal spirit of freedom fills them and gives them the power to fight for liberation and freedom morally, legally, politically, and in countless educational contexts in a world replete with personal and social manifestations of repression and the lack of freedom.”

Likewise in regard to truth human beings are “shaped in the image of God when, filled by the multimodal spirit of truth, they struggle to bring truth to bear critically and self-critically on the many levels of the search for truth.” This involves various forms of advocacy and defenses of empirical truth claims but also the recognition of “the inner connections between the activities of the spirit as the spirit of truth, freedom, and justice.”

Lastly in regard to peace Welker stated that the multimodal spirit of peace shapes “human beings into the image of God within the peaceful struggle against those powers that try to promote a spirit of hostility, hatred, and warmongering.” As he went on to further describe, “in the form of the warm love of family, friends, and those in our immediate surroundings, and in the form of a cool and calm universal benevolence toward all humankind, the spirit of peace acquires its overwhelming radiant and resonating power.” He concluded his series by stating, “It is in this spirit of peace and in love that every individual person and all humankind are elevated to the dignity that comprehends all humanity and are genuinely equipped with the powers necessary for living commensurate with this grand destiny: in the image of God.”

Professor Welker’s final Gifford Lecture explores ways in which the multimodal Divine Spirit of peace manifests itself in particular contexts and shapes human beings into the image of God by inviting us to struggle against those powers which are counter to the Spirit’s fostering peaceful rhythms in the world around us. Given the excellent summary above, I will limit my comments to just a few questions concerning the relationship between the different manifestations of the multimodal Spirit and conclude with a brief remark about the dynamic hopefulness to which Professor Welker’s work points us.

During the final lecture, I found Professor Welker’s use of Kant especially helpful in countering Vegetius’ view of peace as somehow linked with concepts counter to its reality, i.e. war. However, during his discussion, I also found myself wondering about how different modes of the Divine Spirit overlap and relate to one another. Given that, according to Professor Welker, Kant’s vision for peace includes concepts and structures of justice within which the multimodal Spirit of peace can unfold, how should we understand the relationship between two distinct but related modes of the Spirit – in this case, the Spirit of justice and the Spirit of peace? Does their relation imply some sort of hierarchy or prioritizing among modes of the Divine Spirit? Is there some sort of necessary consistency between them that can be articulated? Moreover, given the emphasis on the early Hegel in lecture two and the apparent parallels between his conception of the Spirit and Professor Welker’s multimodal Spirit, is there some sort of implicit synthesis or way of relating these concepts that leads towards progress? To be sure, I raise these questions out of curiosity and with sympathy for the overall project, not as a critique.

Overall, Professor Welker’s lectures have been both cautiously hopeful and immensely practical. In a world filled with all sorts of challenges that might encourage us to abandon the imago Dei altogether, Professor Welker reminds us that there is also a multimodal Divine Spirit fostering among us concrete occurrences of hope in the forms of justice, freedom, truth, and peace; a Spirit which invites our participation should we both discern and courageously embrace it. In the end, perhaps this is something of what it means to bear the image of God; that is, to be caught up in the dynamic and life-giving movements of the Divine Spirit amidst a world filled with opposition to such things. Rather than asserting more rationalistic and metaphysical views of the imago Dei, perhaps we need a more holistic vision for the concept; one that is both dynamic and Spirit-oriented, a vision with human participation in God’s continued activity in the world at its heart and as its goal. It seems to me that such participation might be at the center of God’s vision for the world and its people, giving us good reason us to be hopeful about the future – even if the past and present tend to tell us otherwise.

Superb lecture! Always thought peace as absence of war uneasy as it maybe. Inner peace as a chimera as life and relationships are a struggle. Never the less much food for thought as they say love conquers all. Thank you Professor Welker for a brilliant series of lectures and also thanks to everyone who made them possible

Thank you for your comments! I see my project well understood. There is no fixed hierarchy between the diffent modes of the working of the Spirit. In specific situations and needs, the emphasis has to shift. But I tried to argue for an interdependence and was very glad to see that not only the great theologian Paul, but also the great philosopher Kant stress all four dimensions – justice, freedom, truth and peace.

Michael Welker