Mid Series Reflections 1

In this post Dr Joshua Ralston offers some of his reflections on Senior Professor Michael Welker’s Gifford Lectures thus far. Dr Ralston is currently a Reader in Christian-Muslim Relations in the School of Divinity here at the University of Edinburgh. His reflections can be found below.

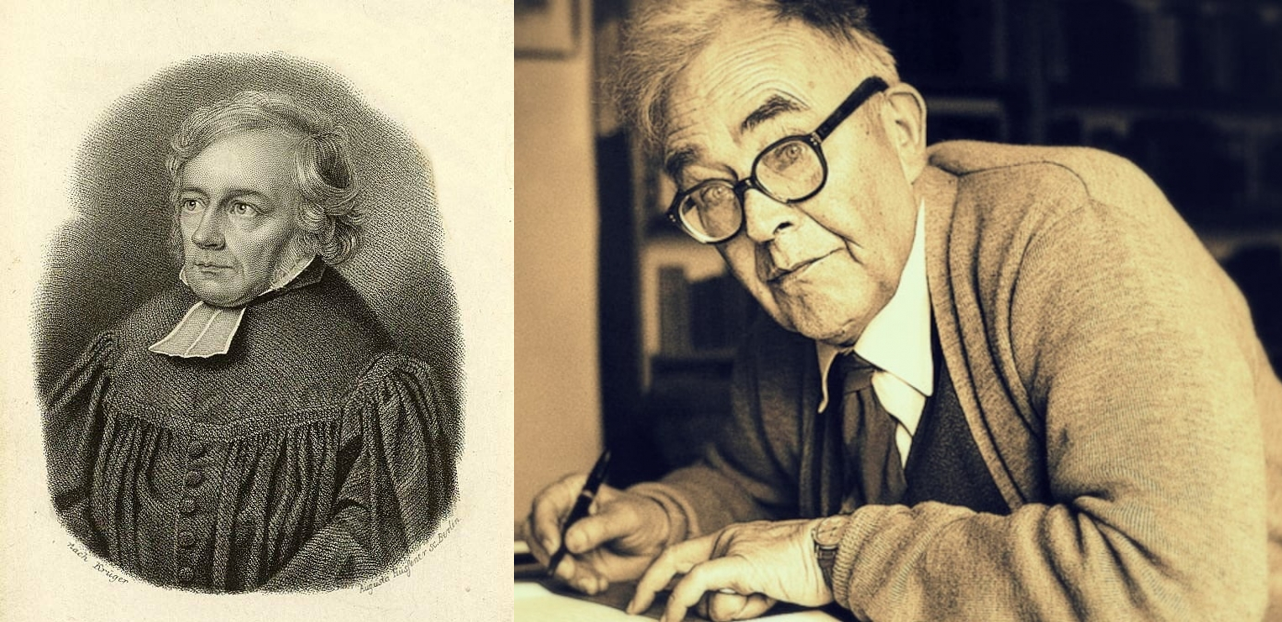

A Schleiermachian Yes and a Barthian No to Welker’s Project

– Dr Joshua Ralston

A habit has developed amongst recent Gifford Lecturers, both here in Edinburgh and at the other three ancient Scottish universities, to take the will of Lord Gifford as a vague suggestion, an outdated curiosity, or a mere inconvenience to be named and disregarded. Rather than offering public and scientific lectures on natural theology, ethics, and the sciences—without appealing to the ecclesial or revelatory as an intellectual justification—many lecturers proceed with their work unencumbered or down right uninterested in natural theology. I won’t name names, but those devotees for Gifford Lectures will surely have some spring to mind. Not Professor Michael Welker! He began his series with a methodological commitment to the project. Promising a bottom up natural theology done in conversation with philosophy, social sciences, and the lived cultural-political challenges of our day. While calling himself a theologian of revelation, he vowed to carry forward his lecture series without reference to Jesus Christ or at least without appeal to him as the standard and touchstone by which theology is judged.

In the first five lectures, he covered the human condition, the challenges of social depravation, and finally turned to the spirit, both human and divine, proposing a multimodal and multidimensional account of the Spirit that struggles toward justice, freedom, truth, and peace. He concluded last night’s penultimate lecture by returning to the question of natural theology. He did so, a bit playfully, by invoking John 4:24: “God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth.” According to Welker, the spirit destines humans toward justice, freedom, truth, and peace and empowers them to struggle against all that crushes, oppresses, and deceives.

Turning to the Spirit is an ingenious way to carry out a natural theology. The term resonates across disciplines, having roots in the biblical texts, German idealism, Christian theology, and broader popular and political discourse. The spirit is not only multidimensional, but its very invocation is multivalent, holding together and cutting across disciplines and themes. And yet its multivalence is also its ambivalence. This lecture series has left me engaged, challenged, and enriched, but also a bit uncertain. I find myself like Barth reflecting on Schleiermacher unsure how to read Welker’s project. Is it that this lecture series has been too theological, a 21st century Protestant Reformed theology done in another idiom? Or is the project too natural and not theological enough, turning the human spirit in general and a particular German liberal version of it into the standard by which both the human and divine spirit is judged?

Let me explore each possible reading of the lectures in brief. Human beings, while glorious and dignified creatures, have so fallen that they are trapped by ills of both their own making and those foisted upon them. Their knowing is caught in webs of self-interest and deception; new life, even the gift of a child, is not free from death and oppression. Natality cannot save us. Fortunately, there is an interruption in this state, one given by the spirit which restores our knowing, heals our illness, and tutors and guides us to new and more abundant life as communities and individuals. Have I just summarised an outline of John Calvin’s Institutes of Christian Religion or Friedrich Schleiermacher’s Christian Faith? Or have I offered a reading of Michael Welker’s Gifford Lectures? If this is a fair reading of Welker’s natural theology, it would be one done that is recognizably Protestant with a Reformed hue and theology carried fully through the third article. But of course, the Spirit in the third article of confession—a theology of revelation—is not any Spirit, but the Holy Spirit of Jesus Christ. And yes, the Spirit will go where it may and is not constricted by creed or church. And yes, all truth is to be celebrated and engaged wherever it is to be found—whether it is called theology or not. But, the spirit also is to be tested. And so if this project is Christian theology in a natural theological key, I am still left to wonder how Welker tests the spirit that destines us toward peace, truth, freedom, and justice?

Here is where I begin to wonder if the natural in natural theology has taken precedent over the theological—coming to be the norm and judge. The lectures have been incredibly careful and convincing at showing a dynamic and multiple vision of the key terms and ideas under consideration. In the lecture on freedom, for instance, Welker has explored the multiple meanings of freedom including freedom of thought and of choice, freedom to dissent and to act justly. And while the multimodal approach resists turning these into a simple hierarchy, the lectures still imply a prioritisation of the social and political freedom of liberal welfare democracy as the best expression of the spirit of freedom. And while I value these expressions of freedom, there remains the sneaking suspicion that liberalism, with a dose of German idealism and Whitehead, has been enshrined as the criteria by which the Spirit is judged. How does this project makes sense of the power imbalances and injustices that often ungird the liberal democratic project and the academy? How does this natural theology of the Spirit guard against turning our own liberal, white, Protestant, and affluent intellectual projects and social imagination into the standard of human flourishing? Where and how does the Spirit’s Nein to our cultures and systems arise? What does the multimodal spirit entail and how is it discerned—if it is the divine spirit—in the world beyond Welker’s interlocutors and focus? Is the divine spirit of Welker’s natural theology too bound to what seems natural to him and to me—as educated white Reformed liberals—that its Pentecostal diversity of being from the crucified One but falling on all, each in their own languages and cultures lost?

Put differently, I want to offer something like a Schleiermachian yes to Welker’s project, but also a Barthian no. At the same time, the multimodal approach that Welker has offered has the possibility for carrying the project into other areas and into dialogue with other thinkers, contexts, and themes. The dialectic of either too theological or too natural need not have the last word. Either/ors are often false choices. It may be that Welker’s project is both fully natural and fully theological, but a natural theology for the 21st century done in a more promising multidimensional fashion that resists the binaries of nature and grace, natural and revealed that shaped not only Lord Gifford, but many of the lecturers that evaded his will.

Recent comments