by Victoria Ma

I. Introduction

Based on the 468 digital archives pertinent to Medical History of British India on the NLS website and the statistics of AntConc, I find that venereal disease was a critical issue in British India during the period of occupation, which has triggered heated debates over the centuries.

As one of the British principalities, British India witnessed a series of outbreaks of various diseases. Notably, in the 1890s, venereal disease was a constitutional crisis among British people and in British colonial India. Philippa Levine asserts that “sexual politics of empire” profoundly “consolidate and secure an authority on whiteness, maleness, and European-ness” (587). Safiya Umoja Noble also argues that society remains silent on gender oppression and racial issues, and there is a long way to go to realise decolonisation and neo-liberation.

In this page, I will employ a feminist perspective to present why and how the venereal disease was spread in British India, the scope of the infection, and the detrimental and profound effects the venereal disease exerted on marginalised colonised people, particularly on indigenous women. The analysis will demonstrate that public response to the spread of venereal disease among British and European troops is a sugarcoated colonial action that imposes oppression and bias on marginalised Indian women.

II. Analysis

The data collected in AntConc and close reading of the texts may confirm the detrimental impacts of British colonisation on indigenous people, particularly harming the marginalised group in British India. The search term “venereal_JJ disease_NN” comes out with 379 hits, among which “syphilis” and “gonorrhoea” are the most common types of venereal disease during that period.

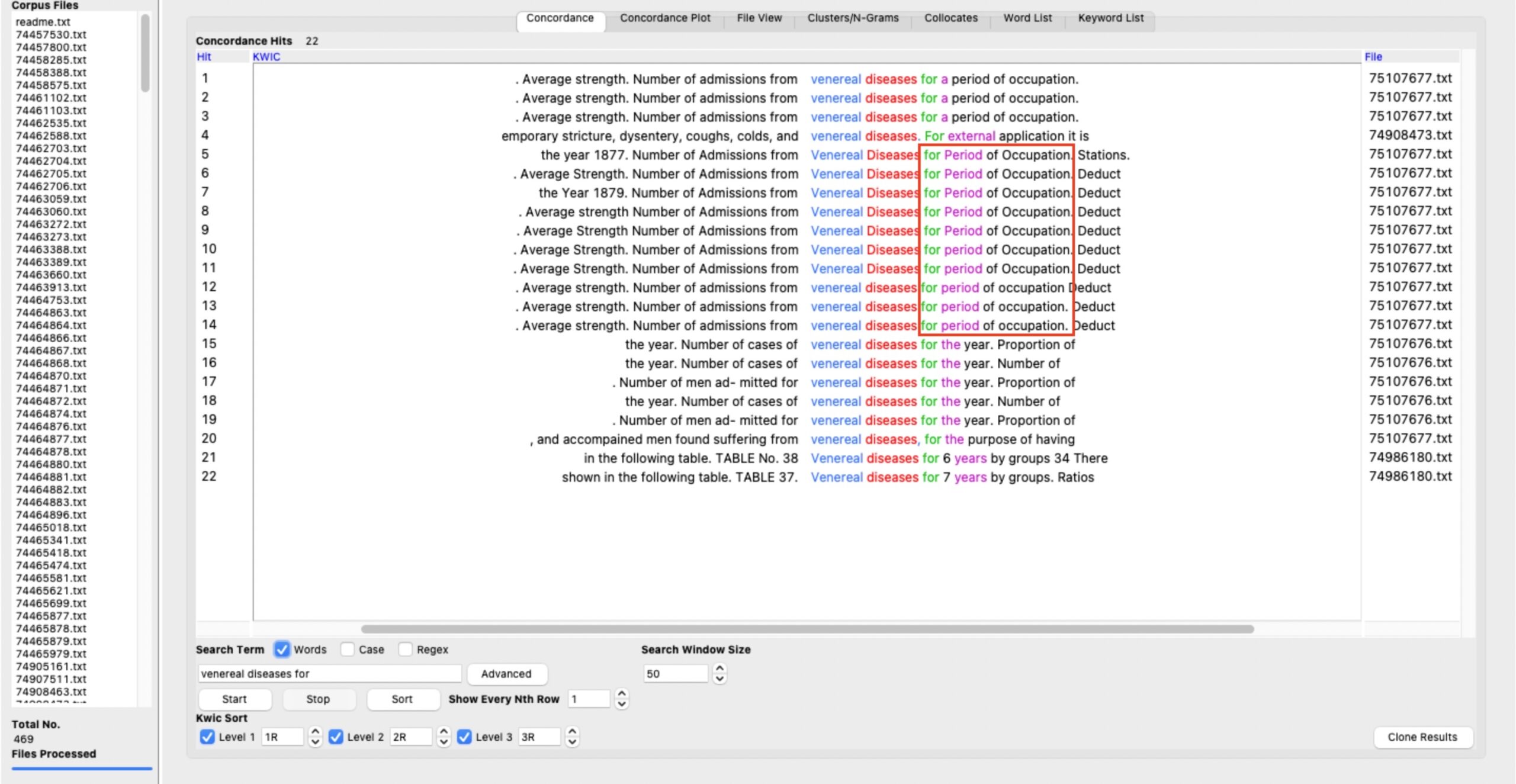

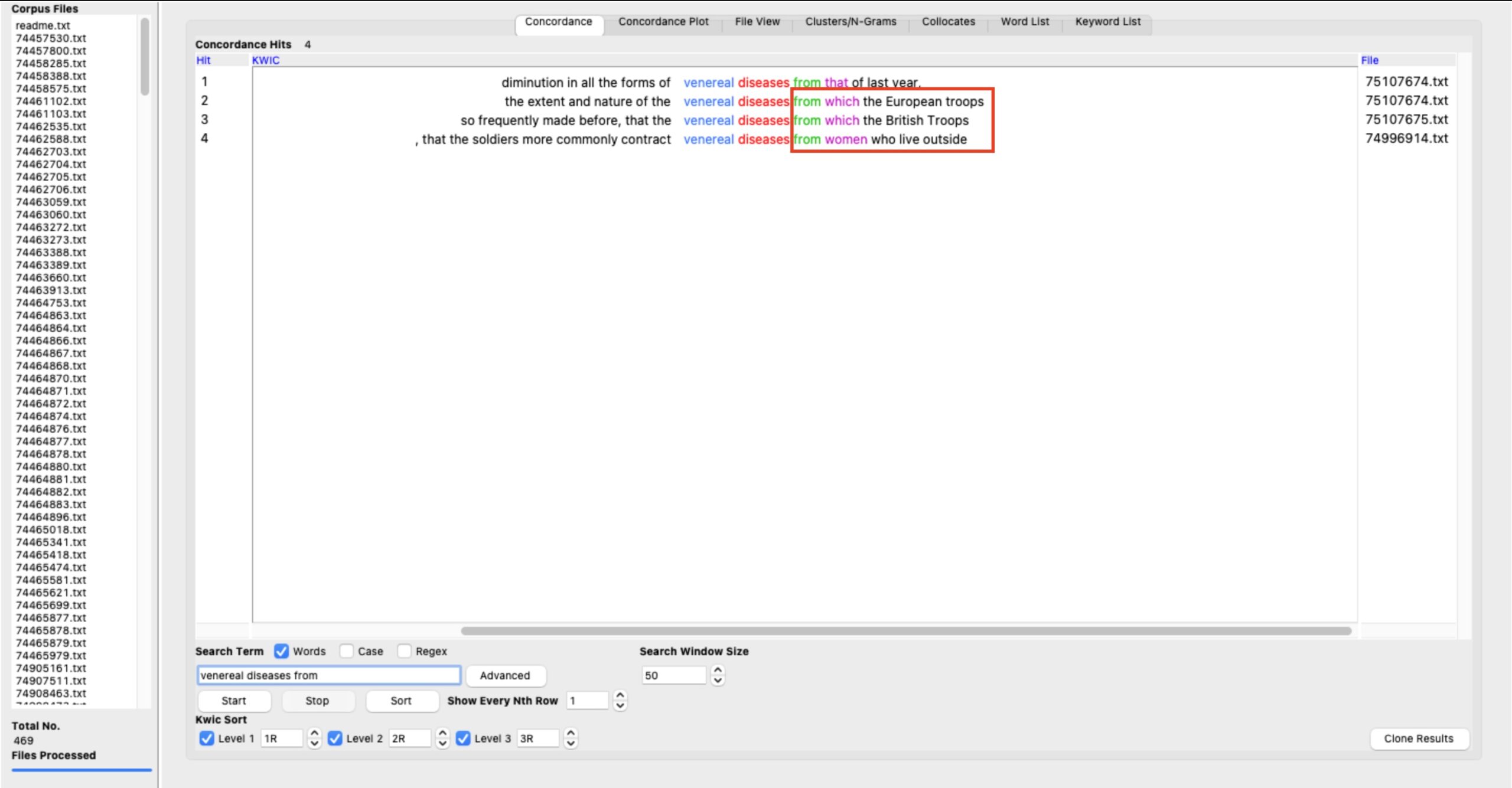

Intending to find out which group of people are susceptible to venereal disease, I focus on the high-frequency Collocates of “venereal disease*” and terms “venereal disease* for” and “venereal disease* from” contribute to the exploration. The term “venereal disease* for” typically appears with “venereal disease for a period of occupation” in KWIC, directly pointing out the connection between the outbreak of venereal disease and colonisation. As for “venereal disease* from”, there are some particular hits in KWIC that note “venereal disease from the European/British troops” and “venereal disease from women who live outside”.

Screenshot of AntConc search results: venereal disease* collocates (venereal diseases for)

Screenshot of AntConc search results: venereal disease* collocates (venereal diseases from)

It is undeniable that most British soldiers were young, under-occupied and bored, and hence sought indigenous prostitutes, which was considered a source of infection. Intriguingly, referring to the accounts in File View, which directly or indirectly present how the venereal disease was spread in British India, it is not uncommon to read lines that adopt comparative attitudes towards troops and (indigenous) women.

For example, some archives claim that “the result would seem to arise from the immunity from disease among women who carry on the trade clandestinely”, and “the soldiers more commonly contract venereal diseases from women who live outside the boundaries of cantonments, and are unregistered”. However, when it comes to British/European troops, the statement changes to that “the extent and nature of the venereal diseases from which the European troops in Thayetmyo suffered during the year 1879” and “that the venereal diseases from which the British Troops have suffered are chiefly contracted from unregistered women”.

In these recounts, women, especially so-called unregistered women, are forced to undertake due responsibilities for spreading the sexual disease. The image of indigenous women has been demonised as people demonstrate that “[…]clandestine prostitution, an evil which is rendered all the more formidable[…]”. Oppositely, the verbs following British and European troops are mainly passive voices such as “be contracted from” or low-degree active verbs like “suffer”. These verbs weaken the power of the soldiers and delineate them as victims of the horrible venereal disease.

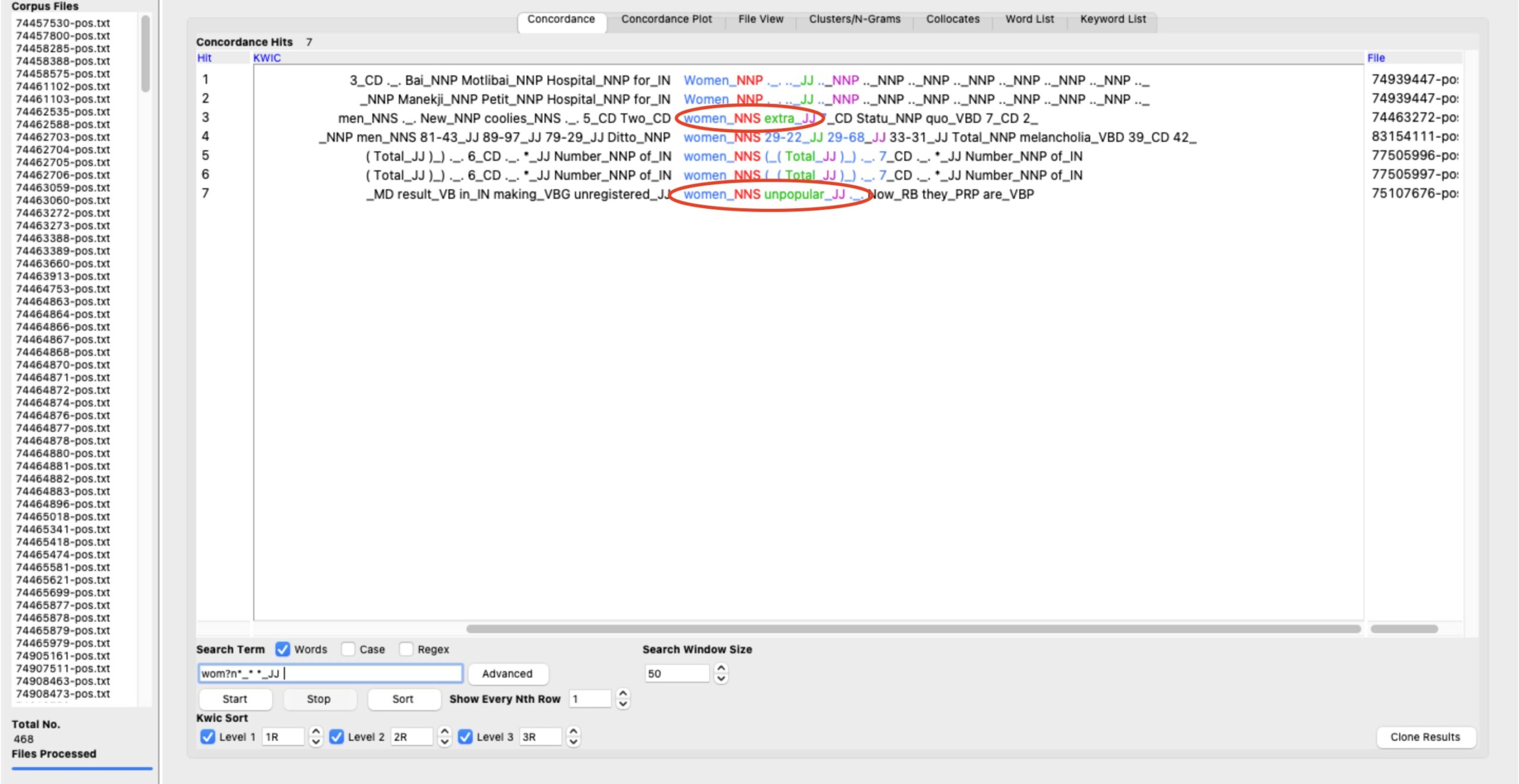

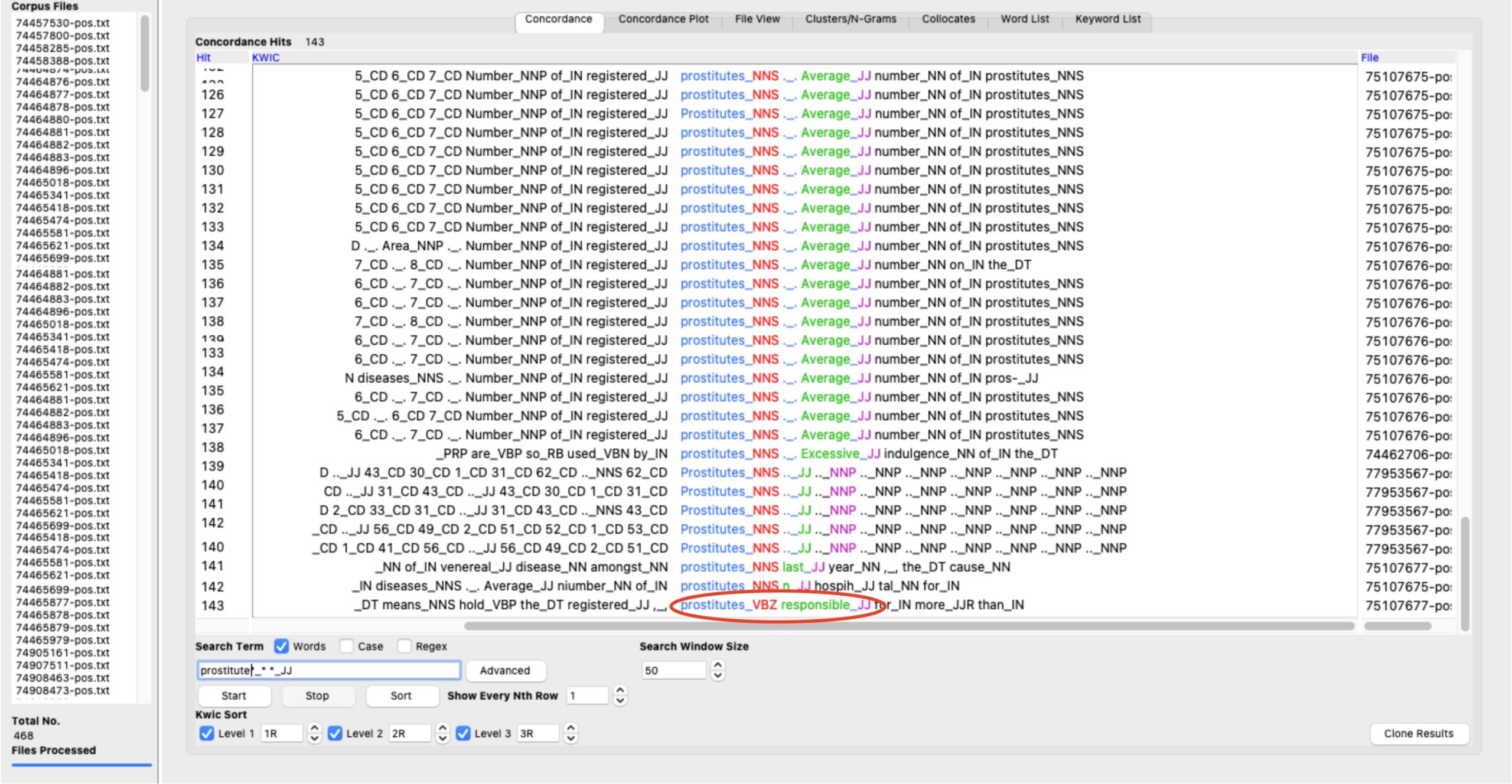

Notably, the spread of the venereal disease has been the eye of the debates about medical history in British India, and many people hold that the indigenous women are to blame. To be specific, “wom?n*_* *_JJ” and “prostitute*_* *_JJ” usually appear with non-positive adjectives such as “extra”, “unpopular”, and “responsible”.

Screenshot of AntConc search results: wom?n*_* *_JJ” collocates

Screenshot of AntConc search results: prostitute*_* *_JJ” collocates

It illustrates that public comments on indigenous women during that period were relatively downbeat, and colonisers generally believed prostitutes take the entire severe disease obligation. Europeans and British people adopt a biased attitude towards indigenous prostitutes, especially unregistered prostitutes. These Indian women are recognised as the natural carriers of sexual disease who victimise and impair the British military force. British Indian women in that period were under dual oppression: one was from the external colonisation while the other originated from the perennial gender issues. Under this dual oppression, the voice of indigenous women was undermined and removed.

III. Summary

The results in AntConc have shown that there is a correlation between sexuality and colonisation.

Frederick Cooper and Ann Stoler uphold that the contention of sex may secure or undermine colonial authority. Notably, there are many such areas in which racial and gendered inequalities commingle. Philippa Levine points out that colonisers intend to solve the issue through colonial enactments, aiming at controlling female prostitution and curbing venereal disease, especially among the British military (581). However, the venereal disease and the prostitution legislation have triggered considerable contemporary debate both in Britain and in India, one of which engages the query if these enactments contribute to hamper the spread of venereal disease or another colonial action that imposes oppression and bias on Indian women.

As Lauren F. Klein argues that gaps, or silences, within the archive are prevalent by the nature of the material they record. The historical archives intentionally stand with the British and European military by depicting them as victims and weakening their proportion of responsibility. However, indigenous women, particularly unregistered women, are not able to speak up for themselves. In this case, more indigenous women were misunderstood as guilty evils even though only those women who consort with European soldiers could be registered at this station. The absence of indigenous female voices might put them in a more marginalised corner where they have to bear triple layers of harm: gendered inequality, British colonisation, and the affliction of the venereal disease.

Photo by Palash Jain on Unsplash