by Justyna Mignotte

I. Introduction:

While the relationship between modern institutionalized medicine and traditional health practices is rather complex – and perhaps especially so in an area as sensitive as reproduction – it was even more in colonial India, where the relations between western midwives and the indigenous “dais” – women helping at labours – appear especially puzzling. I will attempt here to illustrate this phenomenon.

While Dagmar Engels points that birthing was pretty much the only concern of colonial medicine in regard to indigenous female population of Bengal – its health otherwise not of an interest to the colonial administration (224) – even this interest was rather marginal (Geraldine Forbes). “Birthing was not of paramount concern to the men of either culture” (153). It was female activists, like missionaries, or “westernized” Indians, who advocated for modernization and westernization of practices surrounding childbirth (Forbes 153).

The indigenous practices in this matter were somewhat puzzling; in fact they still are, with dais being a phenomenon difficult to fully understand. David Arnold points at rather low social status of dais, traditionally coming from low castes (4-5), as birth was considered impure. The discussion of the role of dais still evokes vigorous response, and there does not seem to be a consensus on the topic.

Some sources see them as respectable and trustworthy, some as harmful and low skilled. Krishna Soman writes: “for ages, dais … have played an important role in birthing care in India, yet they are subjected to a great deal of social and economic marginalization. … they continue to represent a rich heritage of health care and … probably … the only resort for those who are yet to benefit from … development”. Soman sees the changes in maternity care, such as attempts at minimizing the role of dais, as the westernisation of medicine that still occurs to this day (1). Supriya Guha, on the other hand, mentions also the bad sides of dais’ care, such as injuries both to women and infants, and sort of general backwardness of this tradition (2-3).

Historically, during the push for westernization of India, dais were targeted as an embodiment of all that was wrong with maternity care (Forbes 152-153). They were pointed as uneducated, as mostly the occupation was performed by illiterate women, who did not receive western style medical training, learning mostly through observation and practice, and turning to folk medicine and beliefs. The question of dais is going to be a subject of this research into the colonial archives.

Follow the icon of a baby to read about access to maternity service in India ca 1938, accordingly to the Bradfield’s report.

II. Analysis

1. In regard to maternity in general, the analysis of The Medical History of British India might confirm the observations of the scholars: the simple search for “pregnancy” on the NLS website returns ten results: all of them regarding the studies of gestation in animals only. Search for “maternity” returns only one report on the state of maternity care in India, from 1938. The archival documentation might thus confirm what I already mentioned, that the childbearing was to colonial authorities a lesser concern.

Search with AntConc, for “pregnancy”, returns 452 results. The first 10 concern three human pregnancies (although observed during other medical practises, like inoculations); seven regard cattle. Search for “maternity” results in 80 hits. That might confirm rather minor interest in general female ailments, or even pregnancy, and slightly bigger in maternity services, such as birthing premises. Random File View checks might confirm the interest in creating and developing those, as there are mentions of “maternity hospitals”, “wards”, “beds” and “cases”. There are also 26 “hospital” and 17 “government” collocates, which might support the conclusion that the British authorities were interested in developing institutionalized maternal care.

2. In regard to the indigenous dais the simple analysis of the above report from 1938 mirrors the criticism they were facing from the colonial authorities, with description of dais as not having “scientific knowledge” or [knowing] “principles of sepsis”. There is even a statement that “little improvement in the mortality rate can be hoped for until … the untrained and meddlesome indigenous dai is replaced by the trained midwife” (Bradfield 184-185). There is thus a presumption that the poor state of maternity services in India, or related mortality and injuries, are to be blamed on dais.

The analysis with AntConc provides further results: the search for “dai” returns 111 hits, compared to 112 cases of “midwife” and “midwives”. “Dai” is thus mentioned as many times. There could be perhaps a few reasons for that, for example: a) indigenous dais are addressed in the documentation as “midwives” (local midwives); b) there are as many cases of care provided by dai as by midwives, or perhaps c) local dais are mostly mentioned in comparison/contrast to western trained midwives.

Further random check with a AntConc File View provides examples such as: “in welfare centres the staff usually consists of a trained nurse, either resident or visiting, a trained dai and a female sweeper, under direct supervision of the Regimental Medical Officer” or: “There was no Lady Doctor at the General Hospital Kishangarh. Only a Female Dai was in attendance”. These would suggest that apparently dais were allowed to practise, but rather if trained, most likely – in western medicine. It seems that they were also supervised, while the lack of supervision was seen as a negative.

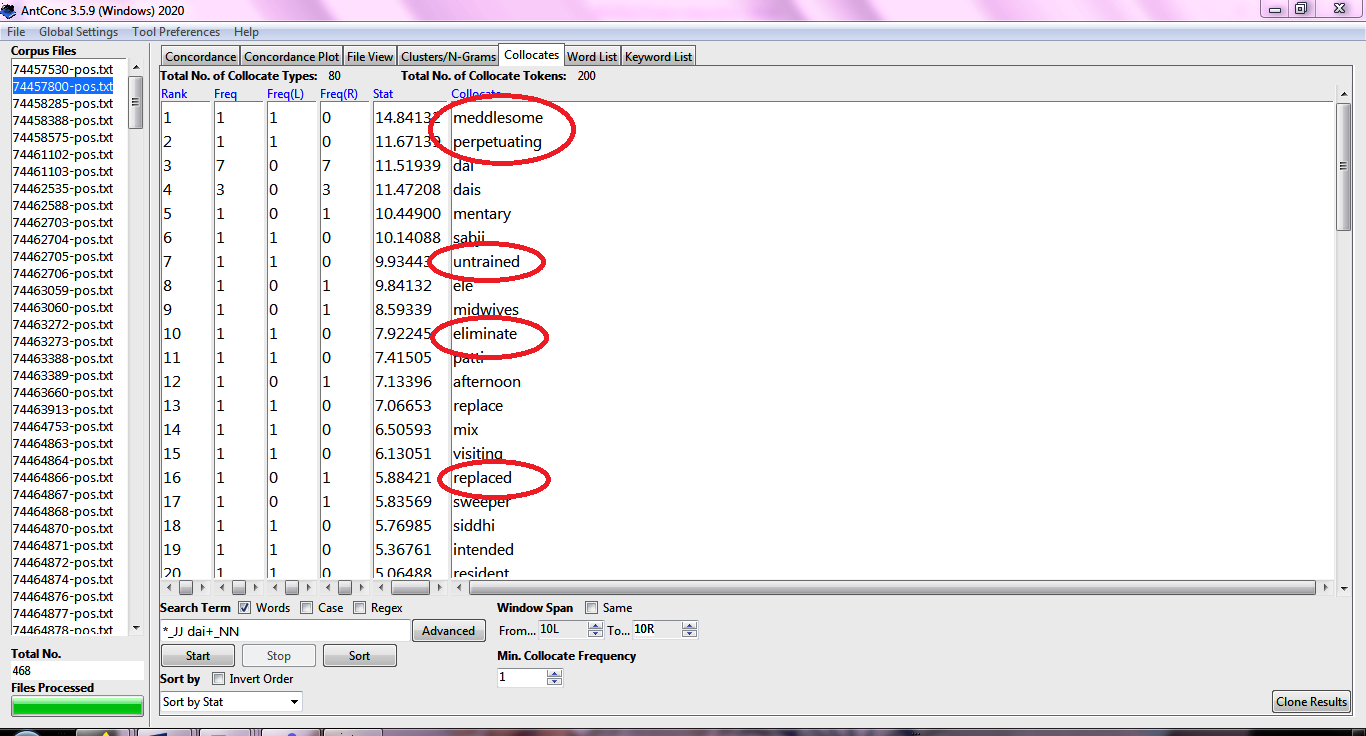

The analysis of adjectives relating to dais returns either neutral or somewhat negative descriptors: from “indigenous” (5 cases) or “local” (4) to “meddlesome” (1) and “untrained” (2). The frequency of neutral adjectives is thus higher; at the same time there seem to be not many positives:

Screenshot of AntConc search results: dai+ adjective collocates

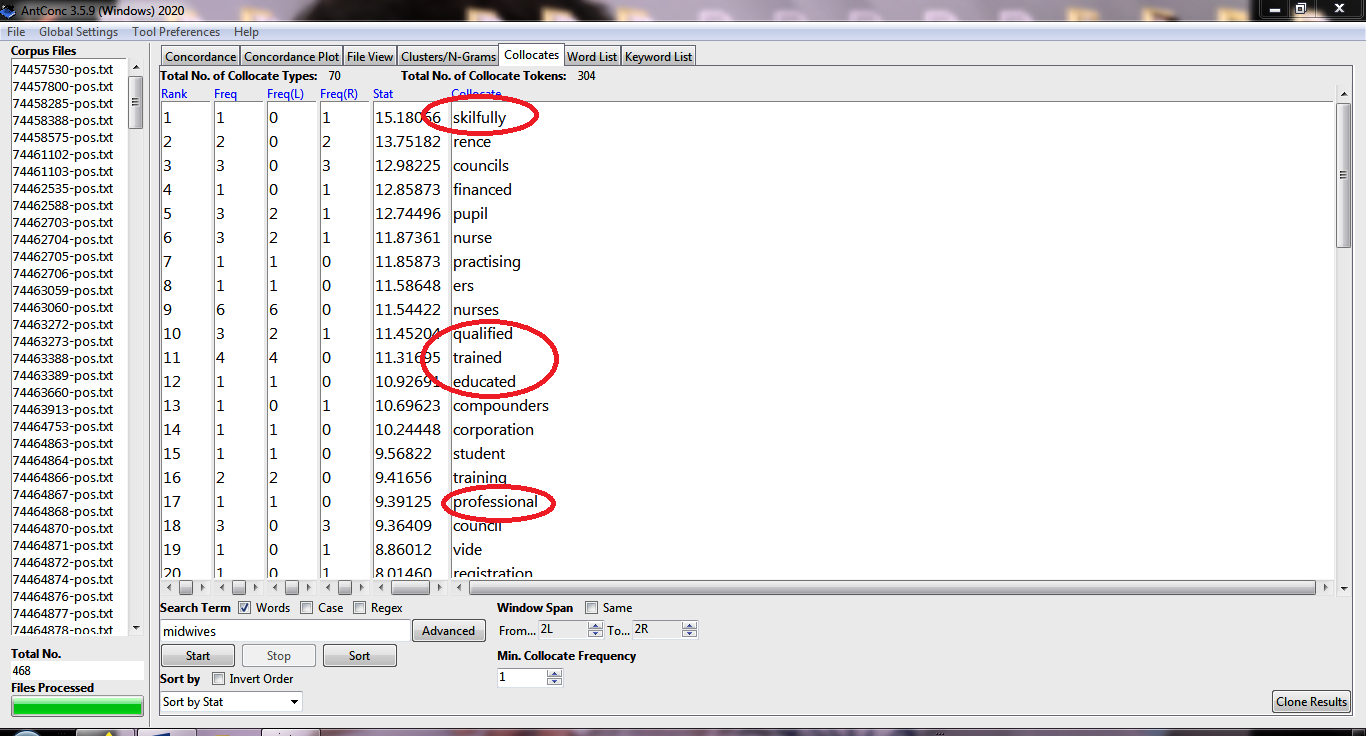

Terms “midwives” appear with collocates such as “skillfully”, “qualified”, “trained”, “educated” or “professional”:

Screenshot of AntConc search results: “midwives”+ adjective collocates

That might suggest or confirm that in terms of medical care the providers were expected to have received western style training and that was considered a norm.

III. Summary

The above analyses suggest that maternity services in colonial India were seen as lacking. There is tendency among colonial administration to see the indigenous dais as in need of training, supervision and adoption of western medical practices.

It needs to be remembered though that at the turn of XIX and XX century maternity services were at the developmental stage in the western world too, and even the 1938 report states that “it must be remembered it is only within last 20 years that … [maternity] schemes for … women have been established in Europe” (Bradfield 185). The strong urge to modernize was thus at least partially due to the general attempts to develop modern healthcare in a certain – centralized and controlled – way. “Bodies were being counted and categorized … disciplined … and dissected, in India much as they were in Britain, France, or the United State at the time” (Arnold 9).

Importantly still, the above analysis, made possible by the combined tools, can illustrate the archival absence that we, contemporary digital humanists, care about. In this case it is the absence of voices: the silence of women, both patients and their attendants, who seem to appear only as the object of the archives.

Photo by Solen Feyissa on Unsplash