By Iosif Pryor

NB: MHBI = Medical History of British India corpus.

I. Introduction

The term ‘idiocy’ is one of such colloquial familiarity that to see it used in common speech raises few, if any, powerful connotations in terms of mental health as we understand it today. However, the term itself has a complex history, reaching far back into the experimental nature of colonial psychiatric medicine as seen in British India.

In Colonizing the Body, David Arnold problematizes a surface-level consideration of medicine as a singular instrument of colonial oppression. Writing that ‘the colonizing force of Western medicine has to be understood as more than a crude device of imperial self-legitimation, a mere “tool of empire”’ (292), Arnold goes on to propose a reflexive relationship between medicine, indigenous populations, and the colonial government.

In this same vein, it becomes clearer how the contemporary colloquial nature of the term ‘idiocy’ can be attributed in part to its use in colonial contexts, as one of the determiners in the arsenal of western psychiatric medicine. Murray Simpson notes that, as well as being an attempt at controlling a colonised population, the deployment of psychiatry allowed empires to curate the ideal ‘model’ citizen at home, through a juxtaposition of the ‘savage’ and the civilised man (From Savage to Citizen, 571-572). As such, the term must be considered simultaneously from angle of reflexive control, where ‘diagnoses’ of idiocy acted both as ways to persecute the indigenous population, as well as a method of standardising accepted social behaviour by demonising the subaltern.

This analysis will examine the relationship between psychiatric determiners and diagnoses, as well as the individuals these diagnoses concerned, with a view to ascertaining the associations of idiocy in a period context and the term’s further reaching implications.

II. Analysis

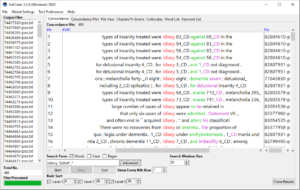

An AntConc query for the term ‘idiocy_*|idiot*_*’ returns 486 results.1 Assessing the usage of the generated terms (‘idiocy’, ‘idiot’, ‘idiotic’, etc.) would prove extremely tedious, so we therefore turn to an examination of the collocates. This search returns evidence that idiocy was very frequently associated with medical diagnoses and terminology, such as ‘mania’ (132 cases), ‘acute’ (99), ‘dementia’ (53), ‘chronic’ (39), ‘insanity’ (28), thereby highlighting the standardisation of the term in medical parlance.

Figure 1: Concordance search results for the query ‘idiocy_*|idiot*_*’

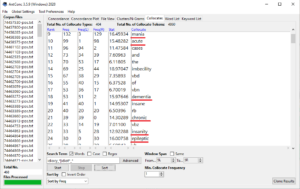

Figure 2: Collocates for the query ‘idiocy_*|idiot*_*’

Searching for key diagnoses from the above collocates independently obtains the following hits:

Mania – 1722 Dementia – 973 Insanity – 5030

The relatively low collocation between idiocy and insanity (at a ratio of 2515:14) as compared to that of idiocy and mania (1722:132) or idiocy and dementia (973:53) further suggests the use of the term in less severe cases of mental illness. Contrasting the two in light of their differing usage – insanity, unlike mania and dementia, being strongly associated with criminality at the time – lends additional credence to this (Ayonrinde, Cannabis and Psychosis, 1164-1165).

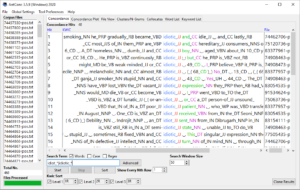

In order to isolate instances where individuals are referenced, we must query AntConc for the term ‘idiot_*|idiotic_*’, returning 47 hits. Combing through these results yields some interesting results, which point to the general unreliability of the term – even internally – when describing the causes, attributes, and effects of idiocy. There are naturally instances where it is used in a loose diagnostic sense, determining a patient to be ‘…continuously idiotic; but… not always in a complete state of insanity’ (MHBI, 74908463), or qualifying various degrees of insanity thus: ‘In about half of those [habitual ganja users] the insanity was of the dull idiotic type, in half the active excitable type’ (MHBI, 74908463).

Figure 3: Concordance search results for the query ‘idiot_*|idiotic_*’

Much more frequent, however, are cases wherein the term is used in conjunction with unseemly or antisocial practices – such as would not merit a psychiatric diagnosis or criminal conviction, but are considered problematic from a social perspective. An 1887 report from the Brigade-Surgeon at Jubbulpore describes a boy, ‘…born an idiot… he was sent to the asylum because he is mischievous and dangerous: he pelts people with stones, damages houses and other property, and in various was is an intolerable nuisance… …he comes under the class of non-criminal lunatics’ (MHBI, 83054536). Further illustrating the colonial attitude towards cannabis is a letter from a Deputy Magistrate in Malda: ‘Persons of defective intellect and idiotic turn of mind, through inability to control temptations, fall into evil company and contract the habit of using ganja…’ (MHBI, 74462706). Key here is the presupposition that, rather than idiocy bring brought on by drug use, it is in fact an ‘idiotic turn of mind’ which predetermines it, further highlighting the increasing vagueness of the term.

Insofar as British colonial power sought to exert control over the region, it also demonised certain religious and social practices which the authorities found problematic, a sentiment noted by Ernst Waltraud (Colonial Psychiatry, Magic and Religion, 57-59). Evidence of such attitudes abound in the archive: ‘He [practitioner of Siddhi] is either a raving maniac or a religious idiot; the inmate of an asylum or a street beggar or the hermit of a cell’ (MHBI, 74462706).2 Further illustrating the weaponisation of the term as a means of erasing local spiritual practices comes from a 1883 report by the Surgeon-Major at Lahore Lunatic Asylum, wherein he describes a patient as ‘…a female idiot belonging to a class of idiots whose head-quarters are at a shrine in the Gujrat district, and who are known all over the Province as “Shad Doula’s mice”’ (MHBI, 77517649).

We end this analysis on what is perhaps the most telling instance of ‘idiocy’, used in line with Simpson’s analysis: ‘The man [ganja user] became useless four years ago, and is still in a semi-idiotic state, unable to do any work and inclined to wander about’ (MHBI, 74908463). Herein, the ‘semi-idiocy’ suffered by this individual toes the line between uselessness and criminality, neither posing a problem to colonial authorities, nor being exploitable for his labour, considered solely in terms of his social function and potential use.

III. Summary

The above analysis demonstrates a clear incoherence in the use of ‘idiocy’ as a medical descriptor, prompting us to consider the term as having very little to do with actual psychiatric medicine. Rather, we see this ‘diagnosis’ used as a means of demonising those whose behaviour, practices, and beliefs are seen as unsavoury.

The colloquial nature of the term ‘idiocy’ assisted the British empire not only in implementing effective control through punitive psychiatry, but also in constructing an archetype of ideal behaviour for its subjects, both domestic and colonial. Waltraud asserts, in Colonialism and Transnational Psychiatry, that the lines between idiocy and other diagnoses are in fact so blurred that they become difficult to differentiate (145-147), functioning more as a sociological descriptor which contrasted acceptable with unacceptable behaviour.

The gaps in the archive are abundant: we are left with a clear absence of indigenous voices, therefore limiting our knowledge of both the region and its people. As understandable as this is considering the nature of empire and colonial record-keeping, it is our obligation as digital humanists not to only to question the terms and context of the archive, but to look to the substantial gaps within it as an area for further in investigation. ‘Idiocy’ is but one term in empire’s vocabulary; understanding its contemporary connection to a complex colonial past is an imperative first step to analysing the far-reaching legacy of empire as it concerns our behaviour, prejudices, and social attitudes, thereby re-examining how even the seemingly minutest aspects of language are reflective of that very same legacy.

[1] This also covers the archaic ‘idiotcy’ which has fallen out of use in contemporary English

[2] Siddhi is a power attained through tantric practice. See The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press, 2013: p. 817

See the map below for a visualisation of asylums across British India. Descriptions of the markers show the frequency with which each asylum is mentioned in the MHBI.

Photo by Diane Picchiottino on Unsplash