by Rachel Spero

NB: MHBI = Medical History of British India corpus.

I. Introduction

It is apparent that the ‘British concept of lunacy was completely different from the Indian concept of the mental malady’ (Jiloha, Lunatic asylums: A business of profit during the colonial empire in India, 84). The prevailing British principles of morality and rationality significantly contributed to the reformation of treatment and diagnosis given to the mentally unwell during the British rule in India. One such reformation was the introduction of labour as a form of treatment, which predominantly supported the economic growth of the British Raj rather than the recovery of the patients doing the work. The MHBI reveals that there was a misdirection of value placed on the economic gain asylums offered, highlighted by the lack of reports present on the diagnosis and recovery of the patients. As Mukesh Kumar outlines, ‘the notes and the language of diagnosis found in the asylum archives were deeply implicated in the strategies of political powers’ (Disciplining the Mind 10). Therefore, it is critical to acknowledge the historical unreliability of such records; instead of treating them as medical evidence, a more accurate approach is to consider the colonial motivations that influenced the creative power of the colonised documents.

II. Analysis

Whilst researching the MHBI, it became immediately clear through comparing search results of ‘lunatic labour’ in context within sentences containing the words ‘labour’, ‘profit’ and ‘worth’ against a search containing the words ‘health’, ‘diagnosis’ and ‘healthy’, that there is a clear disparity between the two. Whilst the former resulted in 130 hits, the latter found only 11 hits. Therefore, it is natural to suggest that a focus on the economically profitable benefits of lunatic labour significantly outweighed the mental health benefits that may or may not have occurred. There are two elements to consider here, the first is whether or not the mental effects of labour were positive or negative, whilst the second and perhaps more poignant is why data indicating the effects are omitted from the journals.

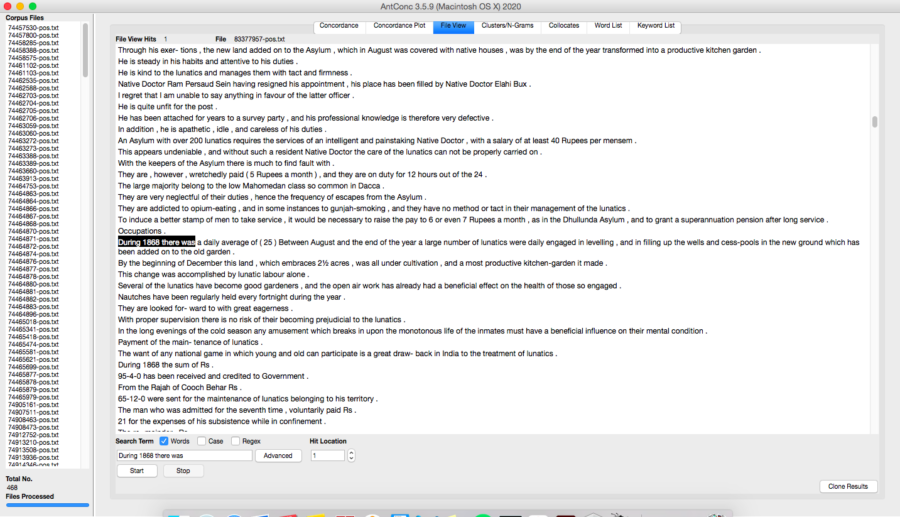

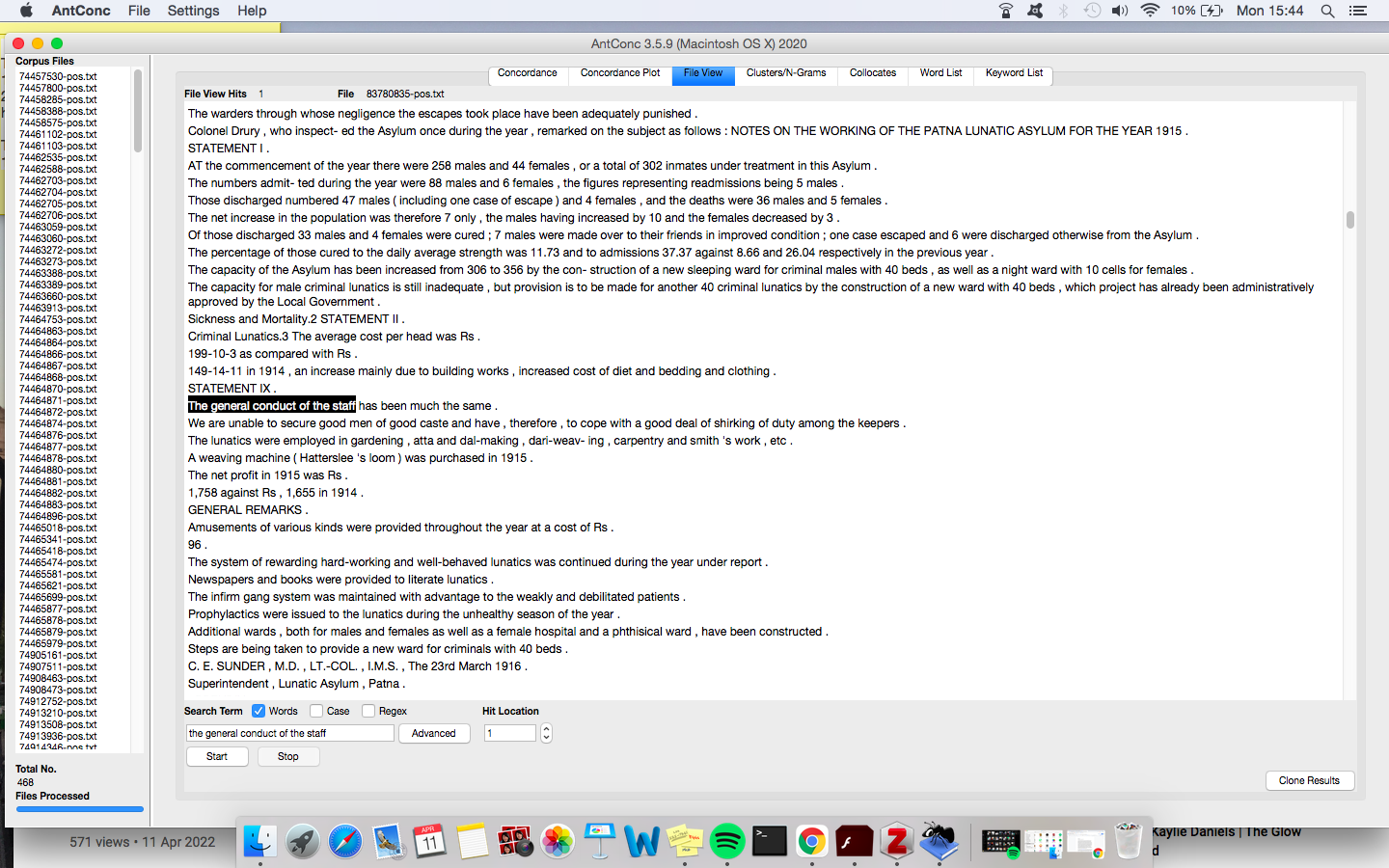

When searching terms such as ‘diagnosis’, no such indications were made of the reasons for which individuals native to India were deemed insane or mentally unwell. There is however a clear distinction made between ‘well-behaved lunatics’ (File 83166290) and ‘non-working lunatics’ (File 82807930). The well-behaved lunatics are described as ‘willing’, ‘cheerful’ and ‘healthy’, whereas the lunatics who did not work are described to make up for, ‘All the deaths, without exception‘ (File 82807930). The seeming narrative being portrayed by the records depict non-working lunatics as unhealthy and suggests that if they were to have been ‘willing’ to work, they too would be ‘healthy’ and functioning. At work here is an example of the colonial vision to transform native Indian “lunatics” into mechanisms by which economic progress and colonial strength can be developed, at the expense of the mental health and authentic reports. At no occurrence do the records acknowledge the reasons for the ill-health of the deceased lunatics and therefore fail to account for the potential mistreatments and previous illnesses of the individuals; instead, the records seem to denote that one of, if not the reason for, their death is their failure to work. The reports also describe the gardens of the asylums in detail (see Fig. 1), outlining the specific tasks of the lunatics however, there is an evident lack of description as to how exactly garden labour contributed to the patients’ recovery, the only outcome measured in this extract is the productivity of the garden, being a ‘most productive kitchen-garden’ (file 83377957). Omitted entirely are the diagnoses’ of the patients as well as their history; although tellingly, there is a large emphasis on the profits made from and the productivity of patient labour.

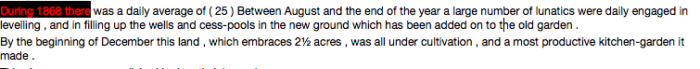

The British framework would have it so that asylum patients were coerced into believing in the moral responsibility to create a profitable product. According to Kumar, the asylum regime ‘actively [functioned to] transform the lunatic, to remodel him into something approximating the bourgeois ideal of the rational individual’ (7). There are two predominant functions at play in the reformation of native Indians by the British, the first is undeniably racial, and the other is economic. The colonial narrative of British superiority provides an explanation for the desire to reform the lunatics into models of the ‘bourgeois ideal of the rational individual,’ despite the basic fact that lunacy was paradoxically defined by its irrationality. The economic profit of asylum labour work is outlined on multiple occasions in the MHBI records. One such example is in file 83780835 (see Fig.2). As shown, the overall net profit increased between the years 1915 and 1914 by 103 Rs. The economic profit made by the British Raj in India was achieved solely by the asylum patients themselves as outlined in file 83377957, ‘This change was accomplished by lunatic labour alone’, and therefore under the guise of positive mental treatment, lunatic labour was in reality, a profitable business, helping to support the existence of asylums and to contribute towards the ‘financial remuneration for the British Empire’ (Jiloha 87).

III. Conclusion

Using AntConc as a tool for computational analysis has allowed both conclusions and questions to present themselves. Analysing the relationship between asylum labour and the economic profitability of such treatment of patients with mental ill-health has unravelled the colonial mission of the British Raj, one that prioritises financial growth over the mental health of asylum patients. The analysis drawn from the MHBI data set also reveals the information that is omitted from these colonial records, questions of the authenticity and reliability of the information documented can and should be raised in an attempt to appreciate the supremacist views and biased standpoints of the individuals who reported these archives. As Ranajit Guha argues, ‘these archives are political distortions that inscribed colonialism in the cultural record by interpolating colonial subjects as irrational, seditious, and in need of rule’ (Risam, New Digital Worlds 50). It is therefore not only necessary to question the validity of these economic records but also the exclusion of diagnosis and recovery reports in order to appreciate the colonial impact on India, its social system and the vulnerable individuals who bore the brunt of labour treatments.

Images

Fig. 1

Fig. 2 (Zoom in on Fig. 1)

Fig. 3

Fig. 4 (Zoom in on Fig. 3)