by Megan Clarke

The Medical History of British India contains information regarding the institutional presence of the lock hospitals, delineating the different strategies adopted for the treatment and control of venereal disease from 1873 to 1891. The digitised archive exposes how the various methods of treatment and control disproportionately targeted Indian women, and by extension, reveals the imperial attitudes towards women and sex workers that underpinned such policies. Through my text analysis, I intend to highlight how the staging of ‘science’ throughout the medical history is closely intertwined with colonial discourses, for ‘The production of an official position on sexuality, and its subsequent regulation, was crucial to imperial efforts to police the various hierarchies which sustained the imperial project, namely hierarchies of race, gender, and class.’ (Peers 146).

As a starting point to my textual analysis, I examined the words that collocate with both ‘prostitut*’ and ‘soldier*’, to instil a comparative framework along gendered and racial lines. A clear delineation between the prostitutes classified as ‘unregistered’, ‘unlicensed, and ‘clandestine’, as opposed to those who were ‘registered’, ‘licensed’, and ‘respectable’ emerged in the former search. The crisis perceived by medical officials was specifically related to the soldiers’ unregistered sexual encounters, for ‘clandestine’ prostitution was identified as the cause of the high rates of venereal disease among the troops; registered prostitutes on the other hand were provided by the government, and subject to regular medical checks. I subsequently examined the words that collocate with ‘soldier*’; while both ‘disease’ and ‘women’ frequented highly, I noted a higher likelihood of cases of the word ‘soldier’ co-occurring with ‘unregistered’ as opposed to ‘registered’ prostitutes, with the former having a frequency almost double the amount of the latter and thus reflecting this contemporary anxiety.

Returning to the results for the collocate search for ‘prostitut*’, a tension between measures of state control and a kind of unruly or uncontainable presence becomes immediately apparent; a semantic field of control (‘number’, ‘registered / registration’, ‘fines’, ‘found’, ‘attend / attending’, ‘public’, ‘control’, ‘admitted’) becomes juxtaposed with the qualities and/or adjectives associated with the prostitutes (‘unlicensed’, ‘diseased’, ‘clandestine’, ‘illicit’, ‘unregistered’, ‘strength’). This tension within the archive, brought to light by methods of corpus analysis, conveys the lock hospitals’ surveillance and examination of the bodies of native women; these strategies are notably absent with regard to the bodies of soldiers, who retained their agency. This disparity in treatment becomes particularly evident when considering the verb forms associated with both ‘prostitut*’ and ‘soldier*’;

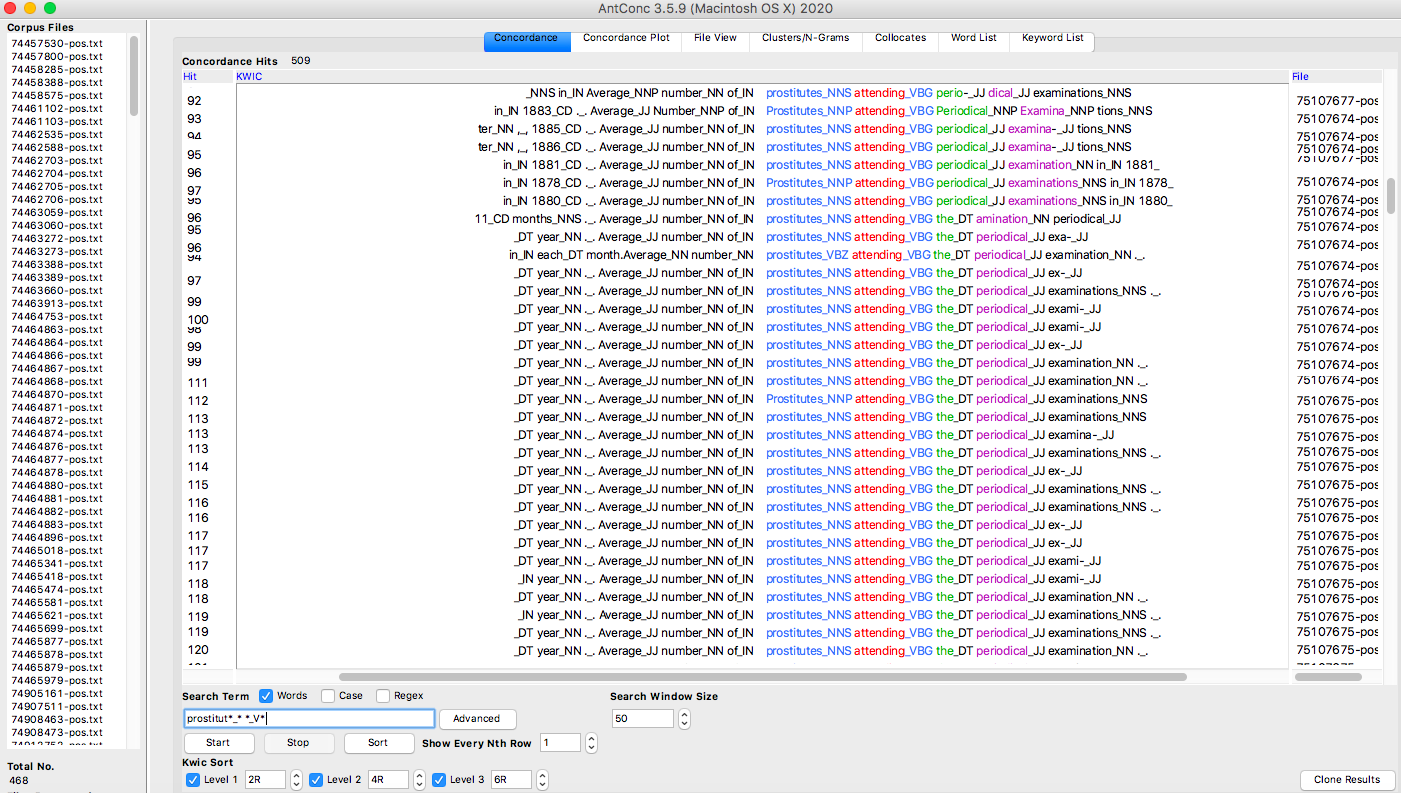

Figure 1: Screenshot of AntConc search results for ‘prostitut*_* *_V*’

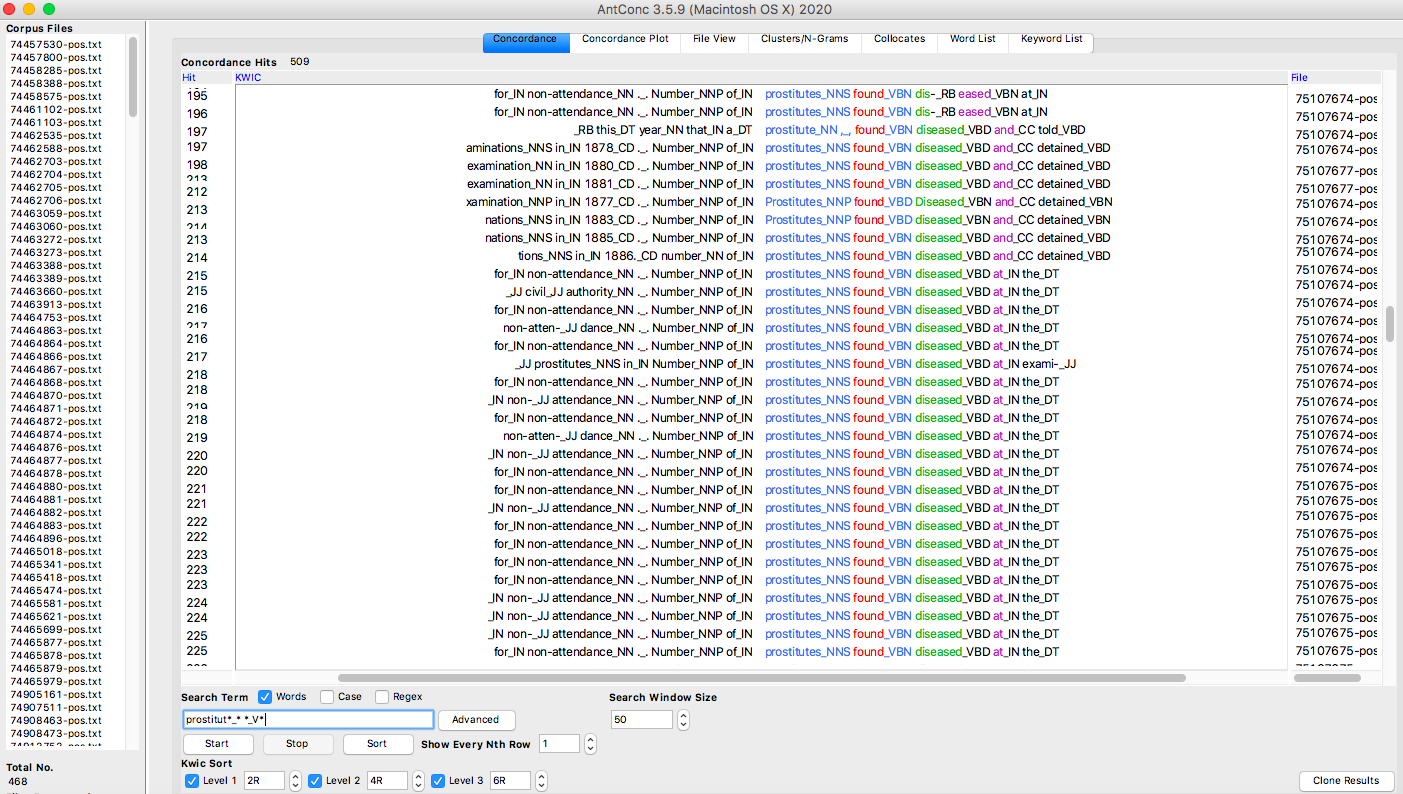

Figure 2: Screenshot of AntConc search results for ‘prostitut*_* *_V*’

Both Figure 1 and 2 illustrate the extensive and disproportionate surveillance of native women’s bodies, for the high number of results for ‘prostitutes found diseased’ (as indicated by Figure 2) is a reflection of how they were subjected to periodical examinations under this coercive and punitive system (as affirmed by Figure 1). There is a marked absence of such evidence of surveillance when carrying out the same search for soldiers (‘soldier*_* *_V*’), thus indicating ‘the glaring omission of including British soldiers within the system of compulsory venereal disease surveillance and incarceration.’ (Hodges 396). This shortcoming in the archival record is a reflection of how a masculine colonial ideology was inscribed within the medical policies in British India, for racial and gendered prejudices underpin the ‘fixation on the prostitute as the site for intervention’ (Peers 160).

When comparing the collocate lists generated for both ‘prostitut*’ and ‘soldier*’ respectively, although both are associated with venereal disease therefore presenting ‘a picture of prostitute-soldier relationships as fluid’ (Hodges 387), the search term ‘prostitut*’ is more so linked with the adjectival form of the word (‘diseased_JJ’), whereas the noun form (‘disease_NN’) appears in connection with the search term ‘soldier*’. Albeit subtle, I argue this difference is indicative of a broader pattern and narrative within the archive, which continually reproduces the notion of prostitutes as the carriers of disease. To interrogate this distinction further, I conducted a collocate search for ‘diseased_JJ’. Without considering function words, the result with the highest frequency was ‘animals’, followed by ‘women’; ‘women’ had a frequency of 24 compared with ‘soldiers’, which had a frequency of 5. This difference supports how a victim-perpetrator dichotomy surfaces within the archive, rooted in colonial understandings of gender and race, as soldiers are conveyed as being seduced by ‘the temptation offered by these women’ (75107676-pos.txt) and lured away from the cantonment by Indian prostitutes; ‘It is not too much to say that they have been already the cause of a good deal of mischief of this kind in this very garrison, and I am of opinion that one woman of this class is more dangerous in herself alone than a dozen of her cleaner or more discriminating sisters.’ (75107676-pos.txt).

The agency that native women are endowed with throughout the reports stood out as quite unusual considering the colonial context of the archive. Agency seems to be strategically allocated to Indian women, for such representations serve both medical policies and military imperatives by rationalising the government’s programme of medical intervention and regulation, which ultimately worked to expand the reach of colonial control. In order to investigate the agency granted to Indian women within the archive, I was interested in the verb forms that appeared in relation to both prostitutes and soldiers. While initially considering all verb forms (‘prostitut*_* *_V*’), I afterwards made my search more specific by looking exclusively at verbs in the present participle (‘prostitut*_* *_VBG’) in order to more easily identify textual patterns. I went through an identical process with the search term soldier(s).

Table 1: This table demonstrates which verbs in the present participle appear in relation to both ‘prostitute(s) / prostitution’ and ‘soldier(s)’ respectively.

| Search Term | |

| ‘prostitut*_* *_VBG’ | ‘soldier*_* *_VBG’ |

| attending | accusing |

| being | arriving |

| belonging | being |

| carrying | cohabiting |

| coming | coming |

| consorting | consorting |

| entering | contracting |

| existing | disliking |

| frequenting | fearing |

| having | having |

| leaving | leaving |

| living | living |

| loitering | losing |

| plying | occupying |

| practising | pointing |

| regarding | recovering |

| remaining | rejoining |

| requiring | reporting |

| residing | returning |

| using | serving |

| suffering | |

| undergoing | |

| visiting | |

| working | |

Although some reports do acknowledge the role of soldiers in the spread of venereal diseases, as indicated by the results of ‘cohabiting’ and ‘consorting’, there nevertheless seems to be a bias towards attributing Indian women with the responsibility of this medical crisis. As foreseen, the results generated frequently confer agency to the prostitutes as the carriers of disease, and are thus consistent with the narrative that pervades the medical history. Their ‘entering’ and ‘frequenting’ of the barracks confers blame, and in attendance with this the soldiers are noted as ‘accusing’ the prostitutes for their contraction of venereal diseases and ‘pointing out the women who had diseased them’ (75107677-pos.txt; emphasis added). Furthermore, the presence of the verb ‘contracting’ is significant for it is asymmetrical, thereby implying that the prostitutes are the source of the diseases. Notably, there seems to be an affective capacity that is solely reserved for the soldiers as they are portrayed as ‘suffering’, an empathetic stance that is not taken with regard to the Indian women. The decision of who suffers and needs protection from disease is made by those authorising the reports, and while the search term ‘protection_* of_IN’ produced results for both the cantonment and the Europeans, both women and prostitutes were absent from the concordance list.

Roopika Risam has explicated how ‘the well-understood link between material archives and colonial power’ does not dissipate within digitised archives, highlighting how ‘traces of colonial violence’ (47) persist in the form of archival absences. One of the shortcomings of The Medical History is its failure to recover the voices of Indian women affected by medical policies aimed at combatting venereal disease despite its reconstruction of a history of the Lock Hospitals, of which they are of central importance. This absence demonstrates how digital archives are inevitably limited by what has been preserved in the cultural record. Despite this limitation, I argue that by applying computational methods to the data derived from the digitised archive, I have been able to draw out broader textual patterns some of which I can measure by frequency to support my intuitions about patterns in language, thus demonstrating how tools from digital humanities can be productively integrated with humanities artefacts. Through my corpus analysis, I have used a combination of methods to foreground the inequities in policy experienced by Indian women, and how medical thought was closely intertwined with a masculine colonial ideology and its understanding of social categories such as race and gender.

Photo by Mohamed Nohassi on Unsplash