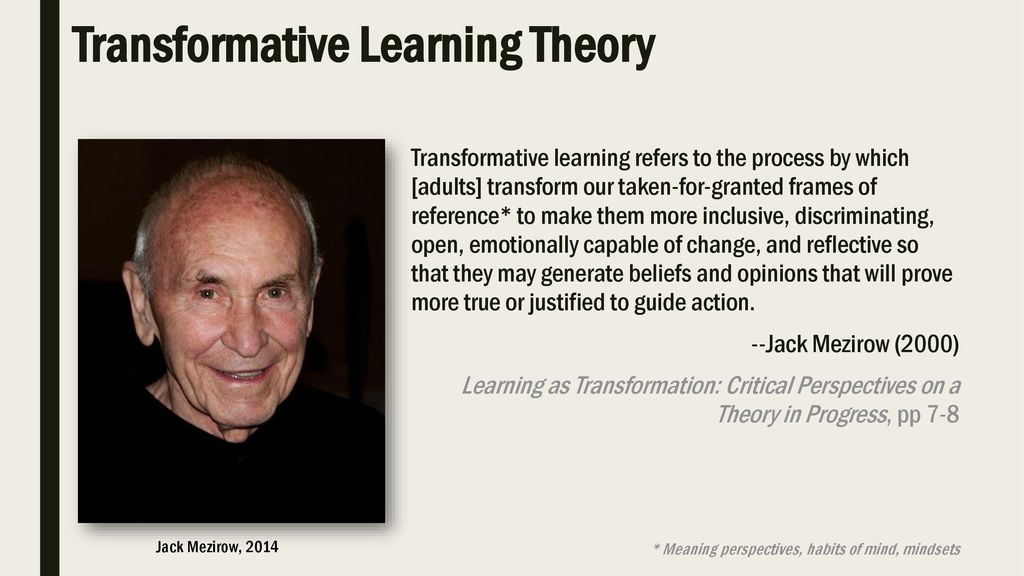

Jack Mezirow (2000) Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. Mark E. Walvoord ; Slidshare: https://slideplayer.com/slide/14578093/

Can technology change the educational paradigm and bring about positive transformation? As educators, we seem to have a common goal, and that is to make the learning process transformational. By that, I mean transformational in praxis (Freire, 1985). That requires a dedication to the art of iteration and reflection, but not any old reflection.

One of the seminal figures of transformative education is Jack Mezirow. He posited that learning brings about change, but that change may not be transformative. The degree of transformation is dependent on critical reflection regarding previously held personal assumptions.

Mezirow came to this conclusion after studying how adults confront new situations in learning. He found that previously held assumptions in adults actually inhibit the internalisation of new knowledge. New learning opportunities could only be actuated when the learners’ past experiences had been opened to critical review. Only then was the learning process transformative.

Mezirow’s theory of transformative learning is as relevant to technology transformation as it is to learning in general. This should be our frame of reference when analysing Blundell, Lee and Nykvist’s paper on moving beyond enhancing pedagogies as, from personal experience, digital technology has not had the expected transformative effect educators imagined it would 10 years ago (Zheng, Warschauer, Lin, & Chang, 2016). Part of the issue here is teachers previously held assumptions on the usefulness of technology from their past experiences. This is not a great foundation upon which to build a transformative approach, as teachers’ EdTech backgrounds vary. If we take into consideration a lack of time for planning and CPD, the results can be seen as not so much one of stagnation but rather an overreliance on past procedures. Education has been dominated by a ‘tell and practise’ approach to teaching and learning. Educators tell students what is worth knowing and students investigate, using critical thinking, collaborating and such like methods before committing to memory what they have found. The issue with this process is it does not encourage transformative personal learning.

The qualitative paper by Blundell, Lee and Nykvist is an explanatory case study of six teachers who are trying to transform their practice using digital tools. The teachers designed their lessons to incorporate innovative pedagogies (Fullan, 2013) that facilitated a constructivist, student centred approach. Although Fullan claims digital technologies afford the possibility of transforming outdated learning approaches, this claim has been widely challenged. In 2017, John Hattie conducted a meta-analyses from over 10,000 studies on the impact of computers in education (Hattie, 2012). Hattie’s results showed the average effect of digital tools to be well below the zone of desirable effects – 0.4 and above. In turn, this study has also been criticised for Hattie’s approach and unfortunate conclusions (Bergeron, Lysanne, 2017).

The qualitative paper by Blundell, Lee and Nykvist is an explanatory case study of six teachers who are trying to transform their practice using digital tools. The teachers designed their lessons to incorporate innovative pedagogies (Fullan, 2013) that facilitated a constructivist, student centred approach. Although Fullan claims digital technologies afford the possibility of transforming outdated learning approaches, this claim has been widely challenged. In 2017, John Hattie conducted a meta-analyses from over 10,000 studies on the impact of computers in education (Hattie, 2012). Hattie’s results showed the average effect of digital tools to be well below the zone of desirable effects – 0.4 and above. In turn, this study has also been criticised for Hattie’s approach and unfortunate conclusions (Bergeron, Lysanne, 2017).

In her paper, ‘The beliefs behind the teacher that influence their ICT practices’, Sarah Prestridge presents evidence that supports the adage that those that want, achieve; far more than those that can. The motivations behind teachers’ actions that have been built up over time seem to be a powerful indicator of future behaviour. As an educator of fifteen years, this is no surprise, as traditional pedagogies tend to sit awkwardly with digital technologies. Even when progressive pedagogical structures have been designed and digital technology incorporated to assist the learning objectives, the success of such projects almost always depends on the teachers’ openness to be challenged. It is to these frames of reference, these attitudes of mind, that Mezirow refers when looking to bring about real transformative change by proactively engaging disorienting dilemmas and using this disruption to alter mindsets.

The research report presented by Blundell, Lee and Nykvist reinforces the perception that teachers’ attitudes to technology and experience of it, directly influences the degree of transformation achieved. The teachers in this research project were subject to disorienting dilemmas, but only the teachers who had the least reservations and valued the novel approaches experienced transformative personal learning and hence, changed their frames of reference.

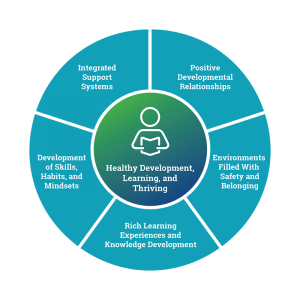

There are other actors that influence this outcome, such as CPD, IT support (Ertmer et al., 2012) and social/historical contexts (Yin, 2009). However, this study is useful in highlighting Mezirow’s theory of perspective transformation. By that, he means how contextual influences act as catalysts for transformation (Mezirow, 2012). In changing the normative process, learners can access student-centric high performance learning. However, it is not just down to the teachers, school leaders need to support this drive by changing routines along with allocating the appropriate resources so that teachers have the opportunities to dialogically engage with challenging outdated frames of reference and habits of mind (Blundell, C, Lee K, Nykvist S, 2020). Then real transformative learning can happen, as much for the teachers as for the learner.

References:

- Bergeron Pierre-Jérôme, Rivard Lysanne (2017) How to Engage in Pseudoscience With Real Data: A Criticism of John Hattie’s Arguments in Visible Learning From the Perspective of a Statistician

- Blundell, C, Lee K, Nykvist S (2020), Moving beyond enhancing pedagogies with digital technologies: Frames of reference, habits of mind and transformative learning

- Ertmer, P. A., Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T., Sadik, O., Sendurur, E., & Sendurur, P. (2012). Teacher beliefs and technology integration practices: A critical relationship. Computers & Education, 59(2), 423–435. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.02.001

- Freire, P. (1985). The Politics of Education, Macmillan [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. (2013). Stratosphere – Integrating technology, pedagogy, and change knowledge. Toronto: Pearson

- Hattie J – (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning

- Mezirow, J. (2012). Learning to think like an adult. In E. W. Taylor & P. Cranton (Eds.), The handbook of transformative learning: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 73–95). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

- Prestridge S. (2012). The beliefs behind the teacher that influences their ICT practices

- Terhart Ewald, (2011). Has John Hattie really found the holy grail of research on teaching? An extended review of Visible Learning

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). London: Sage

- Zheng, B., Warschauer, M., Lin, C.-H., & Chang, C. (2016). Learning in one-to-one laptop environments. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1052–1084. doi:10.3102/0034654316628645

19/11/2021 at 10:19 PM

Hi Laurence

To go back to your title question

‘Can technology change the educational paradigm and bring out positive transformation?’

Often technology is seen as a tool that will enable innovative pedagogical changes and bring transformative experiences into the classroom. Tarling and Ng’ambi argued that instead of being transformative, technology was integrated into existing pedagogical practices in the classroom. Transformative teachers who were ordinarily innovative in the design of their classroom activities used technology in innovative ways. Whereas teachers who used transmission based pedagogies, used technology in tightly controlled, teacher-centric ways. (Tarling and Ng’ambi 2016) Pischetola identified that a core driver of pedagogical choices that led to innovative uses of technology in the classroom was high levels of teacher confidence. Teachers that were comfortable with the uncertain outcomes of using technology in new ways in the classroom, were teachers that were reflective in their practice and were supported in communities of practice in their institutions.(Pischetola 2020) I agree with you that school leaders need to support teachers in building transformative mindsets, allowing time for experimentation and reflection. The education department also needs to be onboard; curriculum should be designed to support exploration through authentic learning experiences and less about content delivery.

Pischetola, Magda. 2020. “Exploring the Relationship between in-Service Teachers’ Beliefs and Technology Adoption in Brazilian Primary Schools.” International Journal of Technology and Design Education, July. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-020-09610-0.

Tarling, Isabel, and Dick Ng’ambi. 2016. “Teachers Pedagogical Change Framework: A Diagnostic Tool for Changing Teachers’ Uses of Emerging Technologies.” British Journal of Educational Technology: Journal of the Council for Educational Technology 47 (3): 554–72.

20/11/2021 at 1:27 AM

Hi Ruth

That’s a helpful comment and reinforces Laurence’s arguments well and brings in additional complementary literature.

20/11/2021 at 1:25 AM

I really liked this post and the linking of transformative learning with the change of attitudes and perspectives associated with effective digital education is well argued. The engagement with concepts and a wide range of literature is well executed and the analysis of the barriers to change of ‘practice memories’ is well made. It will be useful to consider how organisational procedures and systems can also act as barriers to change that shift our perspective away from a focus on teacher or leader deficits and onto the wider entanglements of digital education implementation. But this is a strong post with a clear, critical and cohesive arguments.

21/11/2021 at 3:24 AM

Hello, Laurence.

Your post is very suggestive in many aspects. Thanks.

I would like to comment on the last paragraph, particularly on the idea that teachers’ drive towards a transformative learning experience has to be supported by school leaders, providing adequate resources to engage in a dialogic dynamic to challenging habits of mind and references.

Of course, in principle, I do agree with that. Naturally, school leaders are called to play an important role in creating a transformative environment. Nevertheless, I wonder how symbolic or real could this support actually be. That is, how much room for manoeuver do school leaders have to create and, more particular, to sustain that kind of open environment.

I had an experience that, I think, can be illuminating in this respect.

For some months after the COVID disruption -spring and summer of 2020- I had regular contact with a number of colleagues in Mexico, Spain, Argentina, and UK. Many of those scholars had management positions in law schools and legal research centres, and some others were legal scholars with concerns about the future of legal education, particularly about the impact of the digital pivot imposed by COVID19. We had very interesting zoom conversations -at times, I must confess, refreshed with wine- about this topic. Sometimes, those sessions derived in a sort of coaching and, even, in a kind of therapy in times of understandable anxiety.

I reconstruct my position in those conversations as running along with two general propositions, that expressed not only my ideas but, also, my emotional condition after some years of preaching in the desert about the relevance of digital pedagogies in future legal education. Those propositions were:

1) The impact of COVID on legal pedagogies may look disruptive, but, in reality, it implies only the acceleration of a process that was already going on, as it has happened in other practical disciplines, such as medicine or architecture. So, we have references about how things evolve and, eventually, settle down… and this does not end up having robots teaching law, or law schools becoming digital platforms. What is crucial, now (then), is to seize the opportunity for substantive innovation, and be aware of a cosmetic adaptation (of an example of “gatopardismo”, in reference to the Sicilian romance Il Gatopardo, whose strategy was to change everything in other to avoid real change). If that happens, I said, it would be a sadly missed opportunity.

2) Face this circumstance as an opportunity -with the unusual provision of available time provided by lockdown- to rethink your professional trajectory, and, perhaps, to reorient it. This is a time for renewed perspectives and leadership. In the history of legal education, there are very few windows of opportunity for substantial transformations; we still think and work within the framework of a XIX century legal and political reform… so, again, seize the chance to have an impact.

It was with this spirit that I wrote some suggestions to a couple of friends, Deans of well-reputed law schools, about how I thought that the hybrid model could be adapted to legal teaching, and more specifically about the kind of support that, I considered, students and instructors needed, not exclusively terms access to digital technologies but, also, and more importantly, in terms of pedagogy: sessions redesign, syllabus reorganization, programs adaptations, etc.).

Partially out of courtesy and, in part, also because there were critical times, those suggestions were unusually welcomed, and some of them were discussed thoroughly within their organizations. Nevertheless, as you may imagine, nothing happened, or almost nothing of what I expected and impulsed.

And the reason for that result is rather easy to expose: there were so many organizational constraints that as soon as any operative substitute to traditional teaching was available that had to be taken. Such was the only possible choice for a Dean that wanted to keep his/her position, or for a law professor that didn’t want to invest an unsustainable amount of work and time in his/her teaching – considering, as we commented in the tutorial, that teaching quality is not the most valued asset in an academic career in law. The pressure to deliver programs on time; the financial urgency to attract new students; the centralized decision-making at the higher levels of university bureaucracies and government departments; the capture of the educational processes by IT personnel -after all, usually, they argue for one, quick and simple, solution to complex problems, more investment in new “revolutionary” techologies-, etc. left very little room, if any, to pedagogical considerations.

In sum, this experience has made me -even more- skeptical about the possibilities of substantive pedagogical reform from within education organizations -particularly, at the level of professional schools and university faculties-, not to say, about the impact of individual attitudes and efforts on a systemic pedagogical transformation in those instances.

Of course, I think that that is a fundamental question, of which, needless to say, I don’t have an answer, but I guess that some clues are to be found in the overlapping territories between policy and strategy.

P.S. My apologies for this long comment. But as I already told Pete, this “conversations” stimulate my thinking. It is encouraging to think that, in a certain way, this is a contemporary version of the epistolar conversations that shaped modern thinking.

21/11/2021 at 1:04 PM

Hi Pablo,

Thanks for your comment.

My own view, as a director of technology learning in international private schools, is that ship (‘Can technology change the educational paradigm and bring out positive transformation?) has already sailed. Technology has been an evolving disruptive force for good for quite some time now. It has already changed the teaching and learning paradigm and brought about positive change. QED; Can you imagine where we would be with the COVID shutdowns if the technology structures in place were not fit for purpose. What educators are doing now is just reflective ‘tweaking’.

Don’t get me wrong, there is still much to debate and innovate but this reflective approach is driving the pedagogy into, not new, but established progressive streams that were not, pre-covid getting much traction.

Of course I am generalising. Although both private and public school systems are deconstructing what is happening in this COVID crisis and are responding in context-specific ways, that reflective deconstruction is happening across the industry.

I take part in several international educational conferences every year. The major discussion now is how we build on the paradigm shift that has already happened. However, saying that, I feel that real innovation is at an impasse. The tech we are introducing now, like LMS’s and AI, has actually been around for a long time. For example, I designed a group wide LMS from the ground up in Brasil 11 years ago. The present group I work for introduced their LMS 2 years ago, and it is still not used in the optimum way it was designed for. The majority of teachers across the group of schools are only using it as a repository for homework activities to download and links to external sites. This is something I am working to change, because one benefit of an LMS is data mining and its usefulness in making data informed decisions, something you cannot do if all the LMS is doing is linking to tertiary sites.

In summary, I would say this question is redundant. We are beyond that, mainly because of the havoc COVID is wreaking. However, the change that is happening now is in the pedagogy, as there has not been any real ground shifting innovation in EdTech for sometime now.

21/11/2021 at 3:27 PM

Just to touch on your point about:

It is my experience that this is crucial and there is nothing symbolic about it at all. If STL do not directly take the lead in implementing new pedagogical and technological structures, these new strategies will whimper away until they are defunded.

One paper we were given on this course made that point. I cannot remember which. God knows there have been so many of them ; )

This has been my direct experience. The issue is that teachers set up routines at the beginning of each academic year that include long-term planning, short-term planning then individual schemes of work. Teachers merge this time-consuming planning with activity/assessment feedback and grading, plus all the other duties they are expected to perform. This always means they will need to work outside of their allotted paid timetable.

If senior managers with the backing of the school boards make policy decisions that disrupt the structure the teacher has built, that is going to naturally cause friction and pushback. Most teachers who have been at the job longer than 3 years consider themselves experienced and almost middle managers even if they do not carry that title. Experienced teachers do not like being told what to do by their peers who they consider as equals. Hence, if, as is often the case, middle managers are tasked with pushing through new TEL initiatives and the senior leaders are seen as taking a back seat, the outcome will not be as it was intended.

I’ve seen this scenario played out too many times in different countries with different schools to think anything else.