How much can an organisation’s digital education strategy be based (consciously or unconsciously) on a pedagogical model?

In his foreword for 2015 OECD’s report “Students, Computers and Learning”, Andreas Schleicher states that “technology can amplify great teaching, but technology cannot replace poor teaching”, and there in lies the rub. Technology is not some panacea that brings clarity and purpose to an educational paradigm seeking direction. Covid has highlighted and accelerated the debate revolving around how to make optimum use of the learning support systems our digital era has delivered, but the jury is still out on how best to move forward.

In her paper on ‘Digital pivot, rethinking higher education,’ Valerie Anderson makes the case that traditional educational institutions are slow to adapt to dynamic extraneous variables such as lock downs and the move to online learning, what she calls the digital pivot. She makes the case that because of the present environment, dramatic fast paced change is of paramount importance. Being an educational manager myself, it’s hard to understate how much this sentiment resonates.

I agree with Anderson that it’s important to define what we mean by pedagogy, a term loosely thrown around with varying degrees of consensual exegesis. She refers to Kreber (2010), who defines it as the values and assumptions that guide how learning and teaching occur. We can judge good pedagogy on its effectiveness to equip learners for a successful future appropriate to the learner’s chosen path. That means being able to call on structures from previous situated experiences to navigate successfully future social, emotional and cultural challenges the learner will encounter as they go through life. An effective pedagogy uses formative and summative assessment to track progress whilst developing effective habits that promote autonomy and informal lifelong learning.

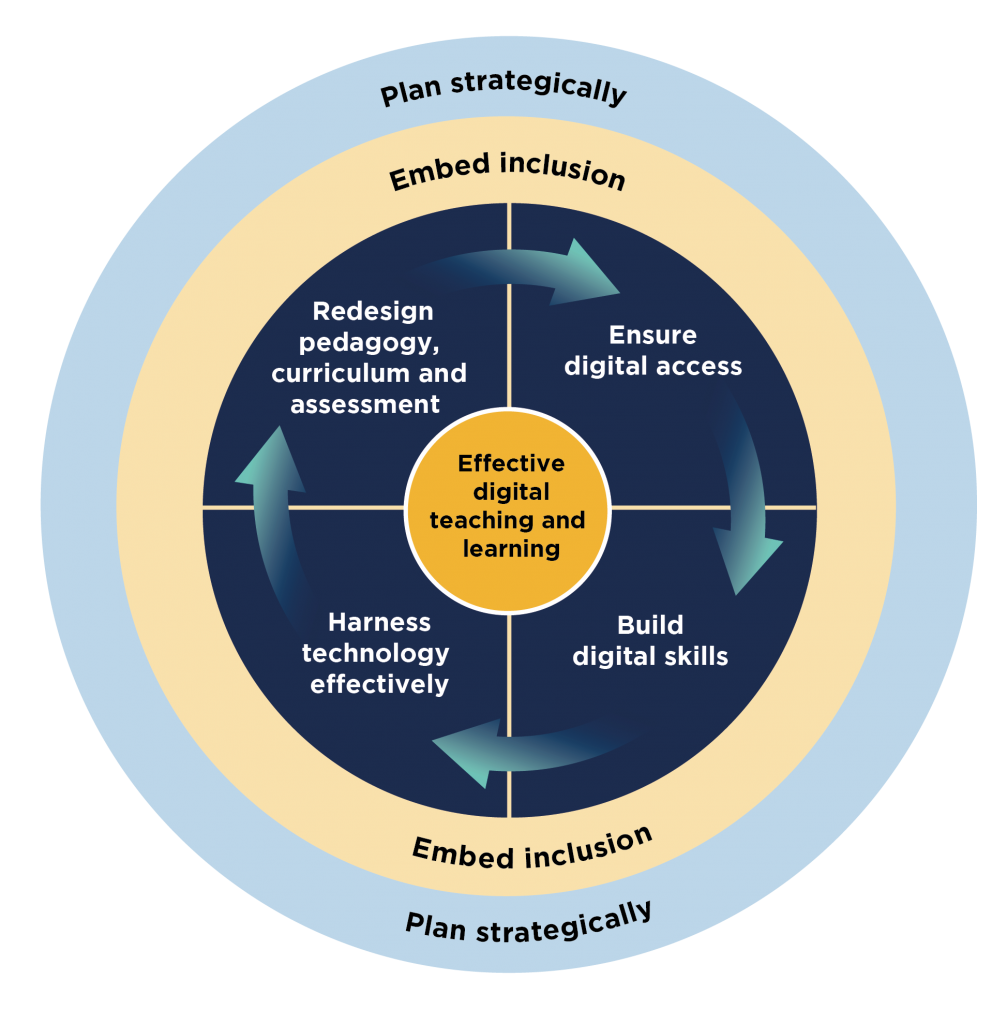

With this in mind, it is clear that the tail does not wag the dog. For those who are enchanted by a technology and determined to fit the pedagogy around the tool, an expensive cul-de-sac awaits. The more sagacious will turn to such models as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), put forward by Fred Davies in 1989. This measures the perceived ease of use of a technology with its perceived usefulness, delivering metrics that can lend to the acquisition process. However, first and foremost, this entire process is determined by the pedagogy. Anderson reinforces this point when stating that a successful digital strategy requires “a clearly communicated pedagogic framework” (Anderson, 2020).

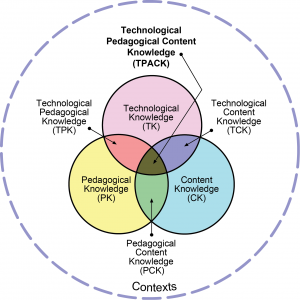

There are many EdTech models that help educators to see how and where technology can be leveraged best. This is the TPACK model, but there are others like SAMR and PICK-RAT.

For the successful merging of pedagogy and technology to occur, academics need to integrate several nodes together, such as knowledge of technology, pedagogy and content. Here, we can use various models that help educators to reflect on their strategies and desired outcomes. These models come under such acronyms as SAMR, TPACK and PIC-RAT. The model’s role is to ask the course designer to think about what is the relationship between technology and the learner.

There is a general consensu that educators should base digital education strategy on some form of pedagogy. What that form should look like depends on the vision of the institution and their USP. However, the belief that pedagogy forms the foundation of any successful technology strategy is ubiquitous.

Whilst I do not disagree with this viewpoint, I do not see it as so black and white. Hamilton and Friesen come to mind in how they defined technology either as a force with inalienable qualities (essentialism) that by its very nature leads educators toward particular progressive pedagogical methodologies or a tool (instrumentalism), a neutral means for realising goals defined by their users (Hamilton and Friesen, 2013). I see educational technologies as both, although not mutually exclusive.

03/11/2021 at 12:39 AM

This has a reflective discussion of Anderson’s paper and the highlighting of Kreber’s emphasis on values. There is, perhaps, a difference between learning as a personal activity and education as a collective endeavour (see Biesta 2012 Giving teaching back to the teacher). I like your comment on TPACK (and others) as objects for reflection by professionals rather than prescriptive models.

Take care with your discussion of Hamilton and Friesen as they were arguing that dominant discourses in education treated technology in either essentialist or instrumentalist terms. They argued that technology should be understood in a more sophisticated and nuanced manner that acknowledges the challenges to essentialist perspectives and that technologies shape pedagogical choices and teaching practices rather than being neutral instruments in the service of predetermined choice. So pedagogical choices are shaped by the layout and furniture in a classroom, where the whiteboard is located, how moveable the furniture is, how the available technology can be used, what pedagogies and practices are associated with the particular discipline being taught, what devices are available, the availability of network connectivity, institutional policies etc… as well as the technology skills of the learners and the technology skills of the teachers, etc. Also recognising that technologies may well change fairly rapidly. What might these factors mean for the question of whether an organisation can or should base its digital education strategy on a particular pedagogical model or should a digital education strategy involve and encourage reflective experimentation and practice with those technologies over time

It might be worth expanding on your analysis of Hamilton and Friesen and how you see the relationship between essentialism and instrumentalism.

09/11/2021 at 8:15 PM

As I understand it both essentialism and instrumentalism are determinist. However essentialism is outcome oriented by that I understand that regardless of how the tool is used it will achieve some type of stated outcome. Instrumentalist views the user as achieving a determined outcome if it follows predetermined strategies, IE, a pedagogy.

Whilst their are always variables that fall outside of these quite narrow definitions, my experience is that both essentialism and instrumentalism have roles to play. The validity of that statement depends on the criteria at work and that can quite varied, and rightly so.

11/11/2021 at 11:26 PM

I think I would go a bit further here and say that essentialism suggests that a particular technology has an immutable ‘essence’ that would mean it would always generate a particular outcome or effect. I’d agree with your description of intrumentalism but with the caveat that different contexts and practices can subvert the essentials of any technology while technologies are not solely instruments of their intended use but can shape and do shape how they are used – as the shape and layout of a classroom will, to some extent, shape teaching practices.

14/11/2021 at 2:11 AM

Hi Laurence

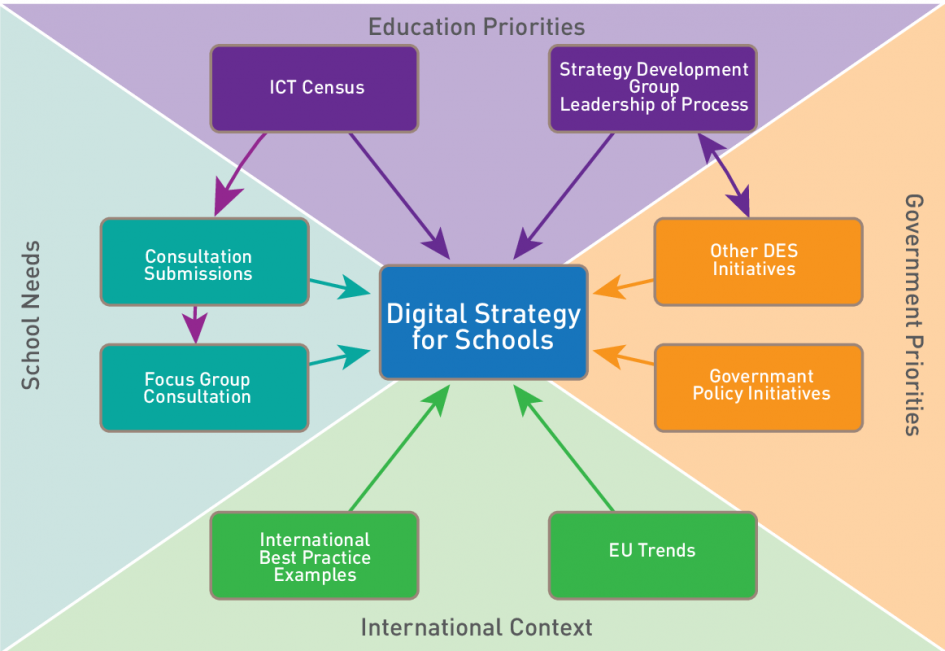

Thanks for your thoughts, I have also revisited that Hamilton and Friesen discussion many times since I read that paper on the IDEL course. I’m a school teacher and so all too familiar with the essentialist narratives which increasingly dominate the digital strategy for schools here in South Africa. It is difficult not to be cynical about the origins of that narrative given the increasing influence of the private sector in the formation of that strategy and policy. The strategy explicitly denies having an essentialist view of technology;

“The innovative nature of the e-Education vision lends itself to critique, especially as much of it is unproven.”

however the proof of the pudding is in the eating..

Our current digital strategy is not pedagogy specific although it explicitly envisages the transformation of pedagogical practices. Although our curriculum statement mandates learner-centred pedagogy, for reasons that I explain in my blog post, teacher-centred transmission pedagogies dominate South African classrooms. There is no guidance, encouragement or time allocated for experimental, reflective pedagogical practice in either the digital strategy or the curriculum statement and without it, it can only be assumed that it is exposure to technology that will lead teachers towards innovative practices.