Seeing (with) Blackford Hill

Drawing, not as a two-dimensional bounded object, but as a process, is a contemporary iteration of attunement with seeing space. Blackford Hill’s Nature Reserve provides a unique opportunity to draw with and not for non-human agents.

Figure 1: Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows 1831 John Constable 1776-1837. (image: Tate)

‘Landscape’ often eludes to eighteenth-century romanticised representations of environments frequently associated with work by JMW Turner or John Constable (figure 1). Posthumanist geographical scholarship, however, has moved away from these essentialisations of landscape as a bounded, frameable entity (as literatures or visual arts), towards a capturing of landscape through processes of human and non-human agents (Brice, 2017). Edinburgh’s Blackford Hill is a designated Nature Reserve with a history spanning 400 million years. Using a post-humanist ontology, engagement with spaces using drawing as image ‘making’ instead of ‘taking’ (Taussig, 2011: 21), may elude to more cooperative assessments of landscape as an ecological assemblage (Haraway, 2016).

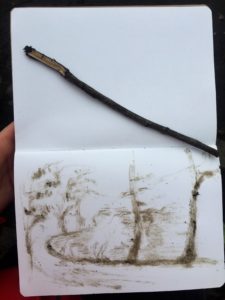

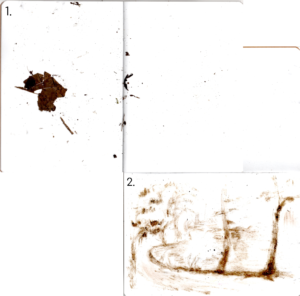

My first exploration was to stick to what I knew. I knew what a landscape should look like, it was the tools I used to create this image which shifted my drawing from a noun to a verb (figure 2). I used moss and peaty mud from the side of a pedestrian path as a medium, and a wooden stick as an applicator. The resulting image is one of combined effort, partly through my physical movements and pressure, but the physical attributes of the mud and moss determined where pigment appeared, its thickness and texture (Drawing 2).

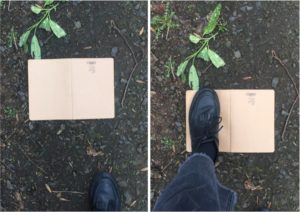

In my second exploration, I reduced my input. Instead representing what I saw, I used my paper to print what would be picked up, imprinted on, and touch my shoe (Figure 3). This was an interesting exercise since I could feel the landscape underfoot, but the visual image on paper (including some small bugs and a leaf), was something I would not have seen had I just been looking at the floor (Drawing 1).

John Berger suggests drawing is an autobiographical discovery of an event (Berger, 1972). Though I concur with the idea of accounting an event, I hold issue with Berger in his anthropocentric undertone. I experienced a transference of agency in creating these images and feelings by using the landscape as a primary tool. With my second exploration, I was unable to see, or to that end, feel, the process of drawing. The sole of my shoe and the ground itself produced a three-dimensional imprint of time and place onto paper. I believe this division of labour in representing landscape acts to reinforce the contention that humans are in composition with nonhumanity (Whatmore, 2006). They are never separate to ecological assemblages of matter.

Dennis Cosgrove (2000) cites pictorial representation as a ‘new’ iteration of Carl Sauer’s ‘classic’ cultural landscape. I question Cosgrove, if we are to take Whatmore’s care for non-human agents as much we care for ourselves, how might landscapes be represented beyond visual means? How can spatial, sonic, haptic and temporal aspects of space can be explored and worked with?

Word Count: 507

Cover Image: Author’s own, 2019.

Bibliography

- Berger, J. (1972) Ways of Seeing. London: BBC and Penguin.

- Brice, S. (2017) Situating skill: contemporary observational drawing as a spatial method in geographical research, Cultural Geographies, 25(1), pp. 135-158.

- Cosgrove, D. (2000) ‘Cultural Geography’, in Johnston, R.J., Gregory, D. Pratt, G and Watts, M. (Eds.), The Dictionary of Human Geography, 4th edn. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 134-8.

- Haraway, D. (2016) Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Taussig, M. (2011) I Swear I Saw This: Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Whatmore, S. (2006) materialist returns: Practising cultural geography in and for a more-than-human world, Cultural Geographies, 13(4), pp. 600-609.