Entrée: Freshly caught climate change

The chemical composition of our atmosphere is changing with relentless haste. An infallible truth which millennials and GenZ have little issue accepting (just consider the recent Youth Climate Strike). So how does the incoming generation consume Earth’s foods?

Taking a position of feminist post-humanism (as influenced by Alaimo, 2010 and Haraway, 2016), I propose a two-part ‘menu’ for unpacking how my changing climate is tasted and consumed, but also how my body is entangled with these changes.

STARTER: TASTING THE LAND

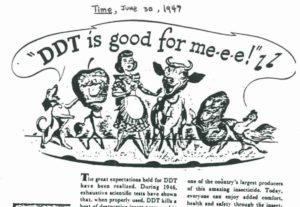

In July 2017 I decided to stop eating meat. Having read Rachel Carson’s Slient Spring (1962), a captivating account of the intrusive chemicals of post-war America, I became aware not only of the chemicals in meat and fish, but of the ubiquity of chemical-use in altering our very nature and natures. The use of chemicals such as DDT (Figure 1) (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) and BHC (benzene hexachloride) on crops from the 1940s, has been widely attributed to human and non-human death and illness (Carson, 1962).

Though many of these chemicals are traditionally ‘tasteless’ as per Aristotle’s sweet to bitter spectrum, they are reacted to by our mouths and bodies (Le Breton, 2017). Studies on fruit flies (which have a similar genetic structure as humans), has shown that a capacity to taste carbon dioxide is possible in humans (Edwards-Stuart, 2009). Though speculative, the concept of super-tasters having higher number of fungiform papillae (test yourself here), suggests that chemical bitterness has the capacity to be tasted by humans. With greenhouse gases on the rise, it is not an impossible claim that some of today’s youth may start to taste our self-altered earth.

ENTRÉE: LIVING AND BREATHING

The human Endocrine system is a network of glands, hormones and organs (including the brain and thus perceptions of taste), which stimulate or inhibit cellular activity (Roberts, 2017). Explained further in the video below, chemicals absorbed by humans and non-humans are known as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs). Symptoms include cancers and infertility, atypical sexual development and altered chemical perception such as taste. Though the video below has its own issues (RE: 50s housewife imagery conflating motherhood with the responsibility of caring for life), it suggests my body’s absorption of environmental EDCs is altering my fundamental biology, as well as the foods I taste per Carson (1962).

Video 1: The Great Invasion – Documentary On Endocrine Disruptors, by El Skin Potions Organic Skincare. (source: https://vimeo.com/142787362)

Though this piece of writing does not contain images of me experimenting, eating, or tasting, it is one of immense personal intimacy. It unquestionable that living in Edinburgh has altered my internal bodily chemistry: Tollcross’ vehicle exhausts or my touching this computer as I write these words. Chemical alteration is the most significant topic I have discussed so far, for it is unquantifiable and not limited to the human sphere; both challenges to the Western primacy of occularcentrism and homocentrism (Alaimo, 2010). Though just one entry point, I propose that we reflect carefully on how we taste, for it is symptomatic of the changing chemistry of our human and non-human environments (MacKendrick, 2014).

Word Count: 496

Cover Picture: Wolfgang Tillmans (source: Tate)

Video: (source: El Skin Potions Organic Skincare)

Bibliography

- Carson, R. (1962) Slient Spring. London: Penguin Books.

- Edwards-Stuart, R. (2009) The sense of taste, in Blumenthal, H. (ed.) The Fat Duck Cookbook. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 473-475.

- Haraway, D. (2016) Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Le Breton, D. (2017) Savoring the world: from taste in food to the taste for life, in Sensing the World (translated by Ruschensky, C.). London: Bloomsbury, pp. 179-228.

- MacKendrick, N. (2014) More Work for Mother: Chemical Body Burdens as a Maternal Responsibility, Gender and Society, 28(5): 705–728.

- Roberts, C. (2017) Endomaterialities. In Stacy Alaimo (ed.) Gender: Matter, New York: Macmillan Interdisciplinary Handbooks.