Shore Scene Soundtrack: painting memory through sound

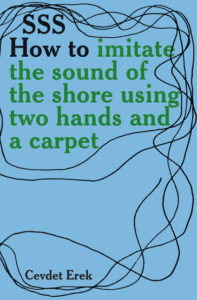

Artist Cevdet Erek launched the 2012 Shore Scene Soundtrack (SSS): an interactive project creating the ocean’s sound through specific hand movements on carpeted material (Figure 1). The act of creating the soundtrack of the sea turned an experience of hearing into an act of remembering, a feeling of a landscape I had previously neglected.

My family come from Caernarfon, and though many things remind me of this place, performing SSS myself conjured up vivid memories of sitting in my grandma’s garden picking crab apples.

Having no coastal areas within reach during my childhood, my experiences of oceans were wholly limited to my regular trips to North Wales to visit my extended family (Figure 2). My three-minute SSS performance was directed by the basic instructions outlined by Erek:

Video 1: Cevdet Erek explaining the SSS project for Kunststiftung NRW, 2012 (source:https://vimeo.com/53667299).

The first point I extrapolate from my experience is that the act of sound recording involves what Paul Carter cites as a ‘poetics’ of performing (2004: 56). My making and listening-back of my recordings are reflective of the technological limitations of my Dictaphone, not limited to my hands and the fibres of the carpet, but a whole-body and whole-environment experience:

Video 2: My performance of SSS, March 2019. (source: https://youtu.be/XxC6qfTHbxE)

My posture as shown in Video 2 reflects a ‘recording pose’ which holds parallels to the electro-acoustic hearkerner of HMV’s dog (Figure 2) (Carter, 2004). There has been an undertaking of academic scholarship into these interconnections between sound and space, especially by Butler (2006, 2007) whose focus on sound walks provides an interesting insight into the role of sound art in space and environments. I would suggest however that SSS takes an alternative experiential approach, in its ability to forge imaginary spaces and memory through sound made outside those places imagined. I have not visited North Wales for over a year now, the longest time I have gone without doing so, and the SSS experience I have when listening back provokes strong longing and shame for forgetting Wales in my everyday Edinburgh life. There was a duality in the remembering for it also meant a prior forgetting of my family, childhood and heritage.

Sound art’s visceral nature lends to a difficulty in its epistemological categorisation as pointed out by Butler (2006) and LaBelle (2015). I argue that the fact sound ‘eludes definition, while having profound effect’ (LaBelle, 2015: xi), is definitive of its very disposition as personal, subjective and unable to be spatially bound. For someone else, just through movement a hand across a carpet, SSS will produce a wholly different embodied and imagined experience. This is testament to the affective power of sonic memory and imagery. In this sense, careful creation of sounds may blur not only what senses are involved (hapticity of moving hands across the carpet, what is heard or seen in the video), but also a blurring of the spaces involved. In this video I was both in Wales and Edinburgh, inside and outside, present and past. Where were/are you?

Word Count: 490

Cover Image: Author’s own (2019)

Video 1: Kunststiftung NRW (source: https://vimeo.com/kunststiftung)

Video 2: Author’s own (2019)

Bibliography:

- Butler, T. (2006) A walk of art: the potential of the sound walk as practice in

- cultural geography, Social & Cultural Geography, 7(6), pp. 889-908.

- Butler T (2007) Memoryscape: How audio walks can deepen our sense of place by integrating art, oral history and cultural geography. Geography Compass 1: 360–372.

- Carter, P. (2004) Ambiguous traces, mishearing, and auditory space, in Erlmann, V. (ed.) Hearing Cultures: Essays on Sound, Listening and Modernity. Oxford: Berg pp 43-64.

- LaBelle, B. (2015) Background Noise, Second Edition: Perspectives on Sound Art. Bloomsbury Academic & Professional, New York.