Feeling ill:

Haptic healing architecture

In 1928 Alvar Aalto designed Finland’s Tuberculosis Sanatorium, using symptoms of TB patients to guide design which responded to sensitivity of touch, light and limited mobility. It is exemplar of the intimate power of architectures to ‘heal’ our ailments, of which the Western visual bias is one. I have analysed my own personal ‘haptic architecture’ to explore my relation to space through touch.

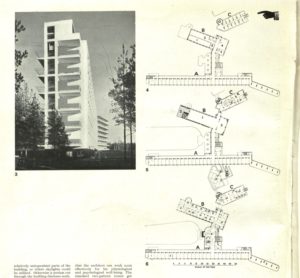

The immediacy of architecture’s visual symbolism has contributed to a painful neglect of the engagement and reunification of the senses in embodied experiences of space (Pallasmaa, 2000). Neglect has been facilitated by engineers of space, but also by myself, in the way my experiences of buildings are visual and minimally tactical. The loss of tactile connection with the fabric of architecture seems to be symptomatic of the use of motion-sensor technologies, and automation. Though I am not denying the utility of these technologies for mobility, I wonder if such a loss of touch within modern architectures calls for a revisit to Alvar Aalto’s Tuberculosis Sanatorium, at Paimio, Finland (see figure 1).

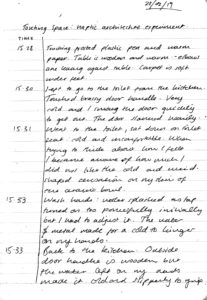

As a synthesis of living and healing space, Aalto’s 1928 design revolutionised functionalist architecture (Woodman, 2016). Needs of patients’ bodies beyond vision were catered for, enhanced and physically scripted into place. Aalto was not designing for the ‘average’ body, but space for the whole body, irrespective of diagnoses. Those admitted to the Paimio Sanatorium were sensitive to light and touch, and struggled to sit upright owing to breathing difficulties (Morton-Shand, 1933). Aalto therefore designed a gentle-sloping wooden chair, which facilitated ease of breath (see figure 2). Metal, cold to the skin, caused unwanted haptic over-stimulation. Wood however enabled this touch, confirming their existence despite their ailments (Hetherington, 2003).

Matthew Patterson (2008), suggests that through movement there is synthesis of the optic and haptic (click Accept and view):

Video 1: Matthew Patterson’s Haptic Architecture video. (source: https://youtu.be/uugjeDl_tPc)

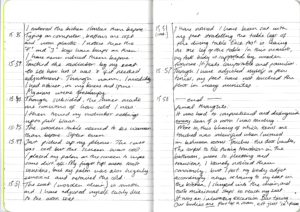

I argue that this synthesis is also achieved by creating environments. Aalto created space which opened a sense of perspective for people who had a limited physical mobility. In a small experiment, I undertook a half hour diary exercise noting down everything I touched and their affects (figures 3-5). Affect is a useful tool of analysis, for it made me tune into bodily reactions to my environment as opposed to rationalised, conscious responses (Gregg and Seigworth, 2010). I moved quickly through doorways when the handles were cold, and slower when they were already open, or wooden. Touching a metal radiator, though it was on, made my arm produce goosebumps and a fleeting shiver to run through my body.

Alvar Aalto’s 1928 design process began with a recognition of the process of doing in experiential situations in space (Pallasmaa, 2000). I wonder, however, if technological advancement is removing the strength of architecture’s bodily affect. I think there is a corporeal desire to touch, a pre-cogitative need for connection with an environment to confirm our being (see Hetherington, 2003). It is not foolish to question how architecture can then insight powerful haptic affects as I experienced, without compromising benefits of modern technologies for disabled bodies.

Word count: 503

Cover Image: Referenced in-text.

Bibliography

- Gregg, M. and Seigworth, G. J. (Eds.) (2010) The Affect Theory Reader. London: Duke University Press.

- Hetherington, K. (2003) ‘Spatial textures: place, touch and praesentia’, Environment and Planning A 35, pp. 1933-1944.

- Morton-Shand, P. (1933) ‘A Tuberculosis Sanatorium Finland’, The Architectural Review (Archive: 1896-2005), 74(442), pp. 85-90.

- Pallasmaa, J. (2000) ‘Hapticity and Time: Notes on Fragile Architecture’, Architectural Review, 207(1239), pp. 78-84.

- Patterson, M. (2008). Haptic Architecture. Available at: https://youtu.be/uugjeDl_tPc [Accessed 3 Feb. 2019].

- Woodman, E. (2016) ‘Revisiting Aalto’s Paimio, Architectural Review, 240(1436), pp. 109-116.