3438 ET Embrun, 3637 OT Mont Viso, 3537 ET Guillestre, 3630 OT Chamonix-Mont-Blanc, the recognisable blue Institut Géographique National, (IGN) maps are a quintessential element of travelling to the French Alps, the equivalent of the 1:25000 (orange) OS Maps in the UK. They open up a realm of possibilities of roads to follow, walking routes to explore, and peaks and circs to tackle. Giving you an understanding of how one valley or pass is connected to the next or what peaks you may be able to see in the distance when at the top of another. How the geomorphology changes as the geological strata changes, and which regions have glaciers to explore or rivers and woods to follow. As you look deeper into the map, your finger picks up a route and you begin to follow, as you do so your memories start rekindling, taking you back to those places you traversed the previous season or from some years ago, with your finger pressed against firmly into the map, as those the harder you press the more you will remember, saying to yourself, that was where we saw that ice bridge, that was where we could see Mont Viso, that was where....

"Many cultures around the world use nursery rhymes to soothe, entertain, and teach their young children. Simple, repetitive songs are often the first steps in learning language – their rhyming and rhythmic structure helps babies, and children and adults too, to remember and retain words." (Dr Jessica Mordsley)

Look at other areas of life where we may use repetition to Learn and reinform, such as through sport and religious practices or as in rehearsing Tibetan Buddhist sacred scriptures or 'Beating the Bounds', an event that takes place in English and Welsh Christian Parishes, traditionally on Ascension day, a common occurrence, especially in those times before maps were easily available, a parish community would walk the boundaries of the parish, usually led by the parish priest and church officials, sharing the knowledge of where they lay, and pray for protection and blessings for the lands. This ritual, one of many that we find in cultures and religions reinforms to build stronger synaptic connections to remembering events, embedding those important aspects of our lives and a sense of stability and continuity.

This is not unique to religious communities, sportsmen and women also go through a sequence of rituals before performing in an event for instance, as seen in examples, such as a high jumper preparing to jump over the bar, simulating the movement of their body and the shape they need to create as the approach and jump, or as you may see Owen Farrell, England's Rugby Union player as he prepares to kick a conversion, who tilts and moves his head and eyes, visualizing the trajectory and path, drawing an imaginary line, from the rugby ball to the point he has focused on, beyond and between the posts, or as seen by a skier preparing their movements for a downhill run (visualization 1) and a final example, as in the film 'Rush' whereby the actor Chris Hemsworth, playing James Hunt, is laid on the floor, imaginary he his in on the racing circuit in his Formula 1 car, wheel in hand and turning it whilst he flaps his feet to indicate the dip of the clutch, change gear, break or to accelerate, visualiaing he sequences of quick movements needing to take place, so they become more intutive and instinctive.

As artists, of course, we often do this through making sketches, studies, maquettes and cameos of ideas, reimagining and rehearsing how something may look before being developed and refined. My own actions of revisiting locations and repeating walks help to remind me, and reinform my own memories for a space; its terrain, geology, geomorphology, light and flora.

Laura Donkers writes, “As contemporary lives become increasingly encoded and distanced from the land, so there are fewer opportunities to directly connect with the places where we live. To address this concern I use ‘field research’ methods such as drawing, fieldwalking, and digital recording, to collect primary observations that trigger understandings of connection, presenting experiences of living “first hand”, in touch with the environment, community and self.”

Laura Donkers 2018 http://www.earthebrides.com/about

Whilst walking, features emerge and disappear within the blink of an eye, reveal themselves then fade away. Deep Time is also present in my thoughts, imagining how a stone was part of rock which was part of a mountain, which was under a 1km of snow and ice, which once travelled through the equator. For me, returning to a specific location and repeating a walk, helps me to remember and reinform those memories, yet at the same time, see the place anew, with a different focus and interest. In essence, when I am walking, 'in' a landscape, I feel my mind is living in the Quantum world and the theory of Quantum Mechanics, whereby different aspect of my brain and sensory inputs can be both on or off or on and off at the same time. I am receptive to the conditions I experience, have a certain level of knowledge for the place I find myself, yet can experience the same location as though for the first time, seeing the same things as though anew and yet for the first time.

Alva Noë (Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley) whose work explores perception and focuses on, perceptual presence and thought presence, as being linked. He states in this book Varieties of Presence, “the world is not simply available; it is achieved rather than given”. This resonated with me, he goes on to say, “The World shows up for us in experience only insofar as we know how to make contact with it, or, to use a different metaphor, only insofar as we are able to bring it into focus. Reason why art is so important to us is that it recapitulates this fundamental fact about our relationship to the world around us, the world is blank and flat until we understand it.”

Whilst visiting locations, I will often make watercolour studies, take numerous photographs and collect rocks. The combination of the experience of the walk, making direct drawing and paintings along with physically engaging, examining and collecting rocks or ‘memory stones’ as I may call them, act as visualization aids and triggers for memories and my perceptions of an event and space when returning to the studio, and when detached from the physical location. In fact, it is arguably this binary relationship between the embodied experience of ‘being in’ the landscape and being in the studio that is central to my enquiry, exploring how we might convey the sense and memory of a place through the process of painting.

In the book entitled 'Whistler' about the American artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) it describes how Whilster researched his series of paintings (known as the 'Nocturnes') made around the river Thames, London, in winter during the 1870's, Richard Dorment one of the co-authors of the book states, "Several witnesses had left descriptions of the memory technique in action. Thomas Way remembered Whistler leaning on the Embankment wall, looking out of the river, then turning his back on the vista and reciting what he saw in 'a sort of chant’ "The houses, the sky is lighter than the water, the house darkest. There are eight houses, the second is the lowest the fifth highest. The tone of all is the same. The first has two lighted windows, one above the other; the second has four.” With his back still to the view, Whistler would then say ‘Now, see if I have learned it’. It was up to Way to correct any mistakes in the recitation that followed. Back in the studio, it was important to commit this mental image to canvas as quickly as possible. With the painstaking technique he had learned in Paris this was hard to do." (Dorment: 121-122)

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne: Blue and Silver—Battersea Reach (c. 1870-75)

For the past few years, I have made a sketchbook before travelling. The reason for making my own sketchbook is that I cannot buy the size and format I would like with the range of watercolour papers inside. Before a trip, I may stain some of the pages with diluted ink, just to have the option of working on a colour ground and a slightly different starting point and atmosphere.

The works created within the sketchbook are often more representational than the finished larger paintings. As I am working on-location, I am working directly from life, I am capturing a sense of a specific space, trying to record the forms of the land; trees, rocks and water. This process may inform me of shapes and connections between natural forms, but more importantly, these direct observations, are in fact informing my memory for shapes and spaces, textures and colours, visualizing through the process of drawing and painting and allowing me to experiment with the actions of the brush or pencil various types of strokes and marks to capture a subject, which are then mirrored back in the studio.

Tim Ingold in his book ’Making’ (2013) talks about Learning from the Saami people of North-eastern Finland giving Ingold a practical task, but did not instruct him on how to complete the task. Although he initially thought they were being unhelpful he soon realised that “they wanted me to understand that only one can really know things – that is, from the very inside of being – is through a process of self-discovery.”He goes on to states, “The mere provision of information holds no guarantee of knowledge, let alone of understanding.” and follows with, “It is, in short, by watching, listening and feeling – by paying attention to what the world tell us -that we learn.” (Ingold: 1)

Both Alva Noe and Tim Ingold articulate exactly what I am aiming to do as a practitioner, through visiting and revisiting a location I am gaining an understanding of my surroundings through using my senses, developing my knowledge of the environment, making memory drawings before putting pen to paper back in the studio and disconnected from the environment I had explored.

The American artists James Turrell has been exploring space and perception through the untouchable phenomena of light and someone whose work has had a lasting impression since first experiencing his exhibition 'Air Mass' at the Hayward Gallery, London 1993. Turrell’s medium is pure light. He says, “My work has no object, no image and no focus. With no object, no image and no focus, what are you looking at? ”

http://jamesturrell.com/about/introduction/ (accessed 19/11/18)

For me, seeing this work for the first time was a real physical and emotional encounter with the work, disorientating my own perceptions and sense of space. The sense to be able to 'reach out', extend a limb or move the body through space as a means of understanding is innate within us and without a physical action, the perception of space is an illusion. Have you ever reached out to do a simple task, such as putting the washing out on a single clothesline stretched across the garden? In my experience, when hanging the first item and reaching out to grab the line I have sometimes missed it altogether and my perceived distance is at odds with the physical reality and the line is not where I had percived it to be.

As I articulated in the text to accompany my solo exhibition 2017/18 entitled ‘Varieties of Presence’ after the book of the same name (2012), by Alva Noë.

“Observing an environment is not seeing it. The space needs to be explored and experienced through a symbiotic relationship between the objective and the subjective, the physical aspects, its perceptual and sensorial experience. We engage with the space through a combination of beliefs, emotions, senses, knowledge, space and time.”

The same place and space is constantly altering, it is not the same place and space it was a minute ago; the environment is active, the trees growing, the weather conditions changing and the observer themselves, are, constantly adjusting their position and focus, reframing their perspective for a space and therefore understanding of that space.

An understanding and knowledge for a location evolves through repeated visits, as one becomes more attuned to the specific aspects and nuances that in one visit may have been overlooked or ignored; exploring the geology one year and the flora the next, slowly the observer develops a greater understanding of a space and enhances their visually perceived knowledge.

It’s not until you set off on a day’s walk do you experience some of these nuances; the cold early starts when the sun is below the horizon and the narrow valleys and corries are cast in shadow, making these spaces look flat and dark, distorting the perspective and interpretation of the perceived space. Then, once the sun has risen above the high mountain tops, the nature of the space is transformed. However, you only become aware of these changes on your return journey, when later that day, and when the earth has rotated by some 75˚ over a 5-hour period, with the sun appearing to have changed position, making these supposed dark and hidden spaces visible, giving a completely different perceived sense of space, mood and therefore, reading."

In his book, Mountains of the Mind, Robert MacFarlane talks about Glaciers and Ice and his seeing how as the light changes throughout the day, changing the effects light on the ice. “The glacier had a different character of each part of the day. In the cold mornings it was crisply white. At noon the sun carved the surface of the ice into grooves of tiny perishable ice trees, each one only a few inches high: a miniature silver and blue forest which stretched away from miles up and down the glacier. The late afternoon light - a rich liquid light - turned the big dun rocks on the ice into tawny beasts and made the pools of meltwater which gathered in the glacier’s hollows, glint like black lacquer." (MacFarlane 2008: 109)

In my own exhibition text I continue to say, "As you walk, your perception of a space and time changes, objects and distances can appear close yet take many hours to walk to. Yet the reverse can be said, for a peak that may seem hours away you can find yourself reaching its summit in little or no time. Similarly, whilst part of the environment you are walking into may look flat yet steep, featureless and without form, can, from another angle, or change in light, appear sharp, jagged and not so steep as first thought. As you are walking at a steady pace you can become aware of how the environment changes the higher you climb; the feeling of the terrain underfoot, the colours, textures, climate, geology, fauna and flora, each playing on your perception and impacting upon your own reading of the space. You are simultaneously a part of the space as much as you are perceiving it."

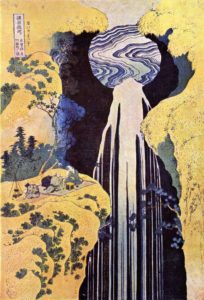

A visual interpretation of seeing a scene from different viewpoint and perspectives can be seen in this work created in 1827 by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), 'The Amida Falls in the Far Reaches of the Kisokaidô Road (Kisoji no oku Amida-ga-taki)', one in a series of works based on a tour of waterfalls in various provinces (Shokoku taki meguri). The perspective and viewpoint of the waterfall in this woodcut, if different form the rest of the image. There is a natural regression of space from the figures in the foreground on the left and the cascading waterfall behind, yet when we turn to view the swirling pool of water from which the waterfall is cascading, this is view as flat and from above, defying gravity.

'The Amida Falls in the Far Reaches of the Kisokaidô Road (Kisoji no oku Amida-ga-taki) 1827.

Katsushika Hokusai [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- Dorment. R, MacDonald, M.F. 1994. James McNeill Whistler Tate Publishing

- Noë, A. 2012 Varieties of Presence Harvard University Press.

- Ingold, T. 2013 MakingRoutledge.