Dr Rachel James recently finished a Daphne Jackson Trust fellowship at the University of Edinburgh. Since obtaining her PhD, she has worked both inside and outside the academic research sector, mostly on a part-time basis.

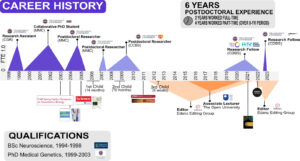

This summer, it will be 20 years since I was awarded my PhD. During these 20 years, I have had approximately two years of maternity leave (one technically a ‘career break’ as it coincided with the end of a contract) and one year in which I did not work. For the remaining 17 years, I have worked either as a postdoctoral researcher (2-years full-time and 4-years part-time over an 8-year period) or in science-related roles (10-years and counting). I have recently finished a Daphne Jackson Trust (DJT) fellowship and am currently at another transition stage of what may come to be described on my academic CV as a third ‘career break’ – a wholly inadequate term, as aside from maternity leave, I don’t feel that I have had a break in my career.

Reflecting on my rather discontinuous research career and the reasons for it, I feel that starting my family and choosing to work part-time are in no small part contributing factors. The current academic career structure of PhD to postdoc to PI involves a considerable time contribution to generate the research outputs and funding applications expected, usually well in excess of a standard 1.0 FTE university contract. Therefore, researchers who work part-time quite literally do not have the time to be competitive on this route. Although there has been encouraging inclusion of part-time and flexible working in current funding schemes, the reality is that researchers are still assessed for these roles under standard research outputs and measures. Until there is better understanding of how these measures relate to individual performance and potential, it is always going to be challenging for part-time workers to progress. In addition, there are so many unexamined biases and inaccurate assumptions made about those that work part-time, that in all honesty, fair assessment requires considerable effort to remove the stigma surrounding part-time researchers.

So what could be an alternative? The availability of part-time research roles that are valued and enable career progression would help. Unfortunately, these seem unlikely to appear anytime soon. Nevertheless, a practical step to this end would be to gain some understanding of what output can be expected from a standard 1.0 full-time equivalent (FTE) contract (i.e., 35 hours a week on a University of Edinburgh contract). Without this understanding, it is impossible to fairly benchmark part-time researchers. If this feels too unwieldy a task, perhaps it would be possible to give an indication of FTE on researcher’s CVs – for example, if you work 50 hours a week, your FTE is 1.4 not 1.0. I started doing this to try and help others understand how part-time work equates to full-time hours. Ideally this would apply to all

researchers if there were to be transparency about output and time, but understandably the motivations to do so are not the same for everybody. In a similar vein, working part-time on a standard research contract of 2 to 3 years means that you have worked that contract for a reduced number of years, dependent on your FTE. A standard DJT fellowship of 3-years at 0.5 FTE means that by the end of it, you have worked for 18 months. Crucial here is the impact these reduced hours have on research output. In my discipline of biomedical research, it would be unlikely for a full-time researcher to complete and publish a research project in 18 months. Research publications are an inadequate measure of ability and potential for us all, but their continued use heavily penalises those that work part-time.

Dismantling the barriers and challenges that are preventing more individuals from being able to participate in part-time research careers can be achieved if the willingness is there. Indeed, levelling the playing field for part-time researchers should be done if the expectation is that they compete for their research careers. On the upside, a career path that has been designed to include part-time researchers could go some way toward alleviating the overwork culture that is still endemic in academic research. That would surely benefit us all.