Guest Post by Henriette Hanky

My ethnographic research into contemporary Osho-related centres and events started in 2019. It has taken me to the Norwegian mountains and Danish countryside, to a stylish Berlin backyard studio and a vibrant neighbourhood in Cologne, as well as to the outskirts of Delhi and bustling Koregaon Park in Pune. All these sites have a connection to Osho (Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, 1931–1990), but the role that the late guru plays in those individual sites differs significantly. These differences can be illustrated by the role that the iconic Osho mala, a string of 108 wooden beads (traditionally used for mantra recitation and meditation) and a locket with Osho’s portrait, plays.

In this blog post, I will explore the multiple afterlives of the mala, which from 1970 onwards came to materialize membership in Osho’s neo-sannyas movement. Like many of Osho’s tongue-in-cheek adoption of elements from established religions, the mala developed a life of its own and has survived even rejection by the guru himself. As it travelled into new contexts after Osho’s death, it has taken on surprising forms that can tell us about contemporary transformations of the movement itself.

Figure 1. The Osho mala (photo taken by the author)

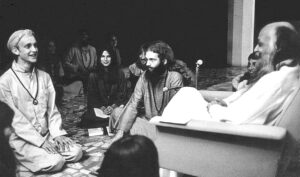

In the 1970s and 80s, you would have recognized an Osho sannyasin right away. With their bright orange and red clothes and the wooden mala carrying a locket with Osho’s portrait, their affiliation was hard to miss. For Osho and his sannyasins, this form of self-emblematizing served several purposes (see Soeffner 2015, pp. 174–175). On the one hand, its enormous visibility caused a stir and gave the sannyas movement attention from the outside. Calling his hippie-minded followers “(neo-)sannyasins” and making them wear saffron robes was a huge provocation, ridiculing traditional Hindu sannyasins and the renunciate tradition in India. Western audiences were particularly agitated by the fact that these youth followed a suspect Indian guru whose portrait they carried around their necks and whom they called “God” (Bhagwan). With their visible identity markers, the sannyasins made waves in their home countries and gave the movement the publicity it needed to grow. On the other hand, the orange clothes and mala were important for the movement internally as they symbolized initiation into the “love affair” of neo-sannyas. It meant surrendering into a master-disciple relationship and the path of relentless self-exploration. In the early period of the movement, it was Osho himself who put the mala around the new sannyasin’s neck during the initiation into sannyas. But even when the movement grew and senior sannyasins took over, the mala still had its ritual significance in marking the change of status and imparting Osho’s energy materialized in the mala to the initiate.

Figure 2. Osho with sannyasins in Pune, 1977. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The mala is a prime example of how Osho played with religion (see Stausberg 2020). Hugh Urban has called Osho a “unique postmodern character, with a remarkably fluid, protean, and shifting identity” (Urban 2015, p. 14), and his teaching and method were as iridescent as his guru identity. While the borrowing of aesthetic and ritual elements from traditional religions served as provocation, Osho also reflexively made use of the powerful techniques that the world’s religions had to offer. Osho knew about the power of ritual, how aesthetic factors enhance transcendent experiences, and how a material object such as a wooden necklace can become a carrier of meaning.

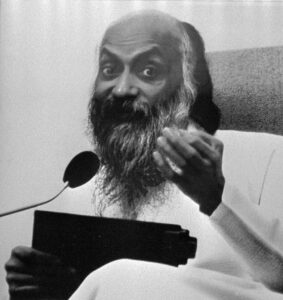

However, it is also typical of Osho’s guruhood that his iconoclasm even applied to his own institutions. After the collapse of the movement’s Oregon commune in 1986, which is well documented in the Netflix documentary “Wild Wild Country” (Way and Way 2018) he blamed his secretary Ma Anand Sheela as well as the commune as a whole for turning the movement into a religion. He declared the religion of “Rajneeshism” dead and abandoned the need to wear orange clothes and the mala. From now on, sannyas was to be an inner affair only:

[T]o begin with and with a world which is too much obsessed with outer things, I had to start sannyas also with outer things. Change your clothes into orange, wear a mala, meditate, but the emphasis was only on meditation. […] I don’t want my people to be lost into non-essentials. In the beginning it was necessary. Now years [sic] of listening to me, understanding me, you are in a position to be freed from all outer bondage. And you can for the first time be really a sannyasin only if you are moving inwards. (OSHO 1986)

Figure 3. Osho, formerly known as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (1931–1990). (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

After Osho’s death in 1990, the OSHO International Foundation (OIF), which mainly consists of Western sannyasins, has continued this path of inwardness. Today, over thirty years after the guru’s death, the malas have completely disappeared from the former main ashram in Pune. When I visited the resort in 2019, I was surprised that, apart from the daily video discourse, Osho’s face is as good as absent within the resort’s walls. Osho portraits have been swapped for Osho’s artwork. Chuang Tzu, Osho’s former bedroom, where his ashes are kept and which had initially served as a samadhi (a shrine commemorating a deceased guru or saint), is now used as a regular meditation hall, much to the dismay of many Indian devotees. In the entry area of Chuang Tzu, an Osho quote on the wall reminds the visitor to look at the moon and not at the finger pointing to the moon. It is Osho quotes like these that undergird the OIF’s individualistic orientation and their devaluation of Osho’s personal authority.

Sociologist of religion Marion Goldman attributes the continuation of the Osho movement to this strategy. Rather than trying to become an institutionalized religion, she argues, the Osho movement has survived by redirecting their focus to becoming a “global cultural influence” rather than remaining a guru movement. The Pune leadership rebranded and popularized Osho’s message by turning him from an “embodied master” to a kind of “avatar” and the ashram into a “hub for worldwide centers and individual clients with varying degrees of commitment” (Goldman 2014, p. 191). In Pune, you can no longer take sannyas. You can however celebrate it as an individual – without guru, without movement, and without mala.

Figure 4. The OSHO International Meditation Resort in Pune, India. Photo from 2008. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

When I took a stroll in the streets around the resort, however, I found out that the malas have in fact not disappeared. They have only moved outside the resort’s walls and been turned into a commodity. You can now buy Osho malas from street vendors and jewellery shops around the former ashram. The OIF’s devaluation of the mala as a ritual object has opened the possibility for locals to make it an economic object and sell it as a trinket to tourists. I remember being torn between wanting to buy one as a curious souvenir and at the same time feeling how potent its ritual significance still was, even for me as a non-sannyasin: buying an Osho mala felt as wrong as buying a driving license.

If even I experience a kind of inertia when it comes to the disenchantment of the mala, how must it be for long-time sannyasins who are emotionally attached to their malas? In fact, during my research and travels, I have come across many Osho places that do not seem impressed by the OIF’s precepts concerning the mala and guru devotion in general.

In Oshodham, an Indian Osho ashram on the outskirts of Delhi, almost everyone, Indians and non-Indians alike, wore their mala. Osho might have discounted the mala, but in Delhi, its presence was overwhelming. In general, Osho’s face was everywhere. The huge Osho portrait in the Osho Dhyan Mandir always had fresh flowers in front of it, and sannyasins paid their tribute to the master by bowing down in front of it when entering and leaving the mandir. I slept in a dorm where every sleeping cubicle had its own Osho portrait, some with sparkling hearts and “Love you, Osho” lettering. In Oshodham, image, video and sound were used to make the absent master present. While this is not at all surprising for an ashram devoted to a guru in general, it makes the contrast to the OSHO International Meditation Resort in Pune even starker. It shows that rituals and ritual objects such as the mala develop a life of their own that cannot simply be overwritten by institutional power.

Oshodham is by no means the only centre that sticks to the old rituals. The Nepali centre Tapoban, for example, regularly uploads videos of their sannyas ceremonies that are closely oriented toward how Osho initiated disciples back in the day.

https://youtu.be/b_iXqwhxeFI

Figure 5. Swami Anand Arun initiates sannyasins at Tapoban, Kathmandu. (Source: YouTube)

The remaining Osho centres and communes in Europe are often still run by sannyasins who have met Osho and serve as meeting places for the scattered sannyas scene. But they also cater to new audiences, younger spiritual seekers who have not met Osho and many of whom are not that interested in having a guru either. These places, of which Osho UTA in Germany and OSHO Risk in Denmark are examples, tend to be pluralistic and welcome the nostalgic Osho devotee as well as the autonomous self-explorer. While the different Osho centres formally adhere to the OIF’s guidelines, they are often pragmatic in adapting the official directions to their local conditions. At OSHO Risk, malas are not a common sight in everyday life, but they are still given to new sannyasins during their sannyas celebrations. While they still symbolize the status change of becoming a sannyasin, they have become private reminders rather than outer membership markers.

Figure 6. At the Danish centre OSHO Risk, some sannyasins wear their malas for special occasions or in private. (Source: Instagram)

Figure 6. At the Danish centre OSHO Risk, some sannyasins wear their malas for special occasions or in private. (Source: Instagram)

A particularly interesting case of a contemporary transformation of the Osho mala met me at the meditation centre Dharma Mountain in Norway. Here, I was surrounded by sannyasins, many of whom wore a necklace with their guru’s portrait around their necks. However, the necklace was not a mala, and the guru was not Osho. These were sannyasins initiated by the Norwegian spiritual teacher Vasant Swaha, and it was his portrait the sannyasins wore. The necklaces came in many forms, some were beads reminiscent of a mala, but most were simple silver chains. The pendants also varied, some were round silver lockets enclosing Swaha’s face, others had Swaha’s portrait on the back while the frontside showed an engraved lotus flower or an Om symbol.

Figure 7. Norwegian guru Vasant Swaha and his community at the Brazilian centre Mevlana Garden. (Source: Instagram)

Figure 7. Norwegian guru Vasant Swaha and his community at the Brazilian centre Mevlana Garden. (Source: Instagram)

The sangha around Swaha is one of several communities that have formed around former Osho sannyasins who claim to have reached enlightenment themselves. In the varied Satsang network that Liselotte Frisk has referred to as a “post-Osho phenomenon” (Frisk 2002), many of the teachers sharing their spiritual insights with their audiences learnt the ropes as Osho sannyasins in Pune and Oregon. Swaha has taken over many of the ideas and rituals of his own master, most importantly the sannyas initiation. While this ritual closely resembles Osho’s way of initiating disciples, the necklace is not part of the initiation. Instead, anyone can buy necklaces and pendants at the centre’s little “Babaji Shop”.

For Swaha’s sannyasins, their necklace can become as meaningful as the mala for Osho sannyasins when their guru was still alive. However, it is not “self-emblematizing” in the same way. As it can freely be bought in the shop, it does not mark an initiation and thus does not differentiate visually between insiders and outsiders. In addition, the Swaha necklace has shed its Hindu religious connotation and instead blends in with other kinds of costume jewellery. For Swaha and his sannyasins, the necklace is not a device to ridicule established religion or shock mainstream society. It still symbolizes the master-disciple relationship but in a form that easily fits in with popular aesthetics.

As the post-Osho scene has become fragmented and diversified, so has the role that the iconic Osho mala plays. As it has disappeared from the former Pune ashram, street vendors can sell it for a profit to cult enthusiasts. At the same time, sannyasins in other places make an effort to retain the mala’s significance or to negotiate between old attachments and new times. In emergent communities such as the sangha around Vasant Swaha, the charisma of the old times lives on, but the mala has been transformed to the extent that even Osho’s face has been swapped for a new one.

Henriette Hanky is a PhD candidate in the Study of Religions at the University of Bergen.

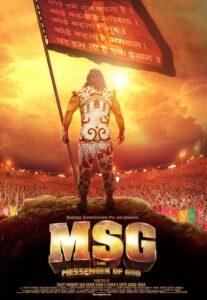

Still from MSG: The Messenger (2015)

Still from MSG: The Messenger (2015) But, once in, you are treated to such a never-before-seen roller-coaster of wooden acting, whiny diction and cringing parade of crazy costumes that it’s tad difficult to look away. Mounted on a massive scale of real human extras that great epics from Hollywood would be envious of, MSG with its curious hook of ‘what next and how much bigger…’ had the B-Movie fan in you glued to the end. It’s one of those unintended movies that attract cult viewing ‘for being too bad to miss’!

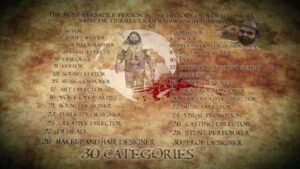

But, once in, you are treated to such a never-before-seen roller-coaster of wooden acting, whiny diction and cringing parade of crazy costumes that it’s tad difficult to look away. Mounted on a massive scale of real human extras that great epics from Hollywood would be envious of, MSG with its curious hook of ‘what next and how much bigger…’ had the B-Movie fan in you glued to the end. It’s one of those unintended movies that attract cult viewing ‘for being too bad to miss’!  MSG is a unique aspiration exercise in India’s most prolific desi super-hero franchise (five films in two years – MSG 1 & 2, MSG: The Warrior Lion Heart 1 & 2, and Jattu Engineer), written and produced by Ram Rahim. He also is its co-director, co-costume designer, co-choreographer, co-art director, co-cinematographer, co-editor, co-action director, stuntman, lyricist, singer, music director and of course, the lead actor. Ram Rahim thus broke Bollywood’s long-standing record of a multi-tasking Manoj Kumar, who used to write-direct-edit-produce-and-act in most of his later home productions.

MSG is a unique aspiration exercise in India’s most prolific desi super-hero franchise (five films in two years – MSG 1 & 2, MSG: The Warrior Lion Heart 1 & 2, and Jattu Engineer), written and produced by Ram Rahim. He also is its co-director, co-costume designer, co-choreographer, co-art director, co-cinematographer, co-editor, co-action director, stuntman, lyricist, singer, music director and of course, the lead actor. Ram Rahim thus broke Bollywood’s long-standing record of a multi-tasking Manoj Kumar, who used to write-direct-edit-produce-and-act in most of his later home productions. Breaking records, incidentally, seem to be a fascination for Ram Rahim, with each of MSG’s song and dance extravaganzas unfolding on an auditorium size-stage with a million plus extras. The Google credits Ram Rahim and his Dera with multiple world records from planting most trees in a single session to organising camps with record blood donors, most blood pressure readings and diabetes screenings (in a day), the largest display of oil lamps (1,50,009 lamps), the largest finger painting (3,900 m²), the largest vegetable mosaic (1,858.07 m²) to even the most number of people sanitising their hands simultaneously (7,675).

Breaking records, incidentally, seem to be a fascination for Ram Rahim, with each of MSG’s song and dance extravaganzas unfolding on an auditorium size-stage with a million plus extras. The Google credits Ram Rahim and his Dera with multiple world records from planting most trees in a single session to organising camps with record blood donors, most blood pressure readings and diabetes screenings (in a day), the largest display of oil lamps (1,50,009 lamps), the largest finger painting (3,900 m²), the largest vegetable mosaic (1,858.07 m²) to even the most number of people sanitising their hands simultaneously (7,675). At heart, MSG is meant to be a patriotic film with a reformist heart that celebrates a range of Indian political ideologies from Gandhi’s message of winning one’s opponent through non-violence to PM Narendra Modi’s ‘Clean India’ campaign. Ram Rahim’s on-screen entry is preceded by a collage of leaders from India’s Independence movement like Gandhi, Sarojini Naidu, Madan Mohan Malviya, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, even Lord Mountbatten, (though there is no sighting of Jinnah).

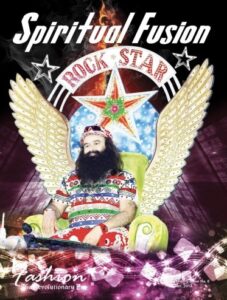

At heart, MSG is meant to be a patriotic film with a reformist heart that celebrates a range of Indian political ideologies from Gandhi’s message of winning one’s opponent through non-violence to PM Narendra Modi’s ‘Clean India’ campaign. Ram Rahim’s on-screen entry is preceded by a collage of leaders from India’s Independence movement like Gandhi, Sarojini Naidu, Madan Mohan Malviya, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, even Lord Mountbatten, (though there is no sighting of Jinnah). Ram Rahim addresses himself as a fakir, but is seen in elaborate never-repeating costumes that feature some heady imaginations with bling that you would ever see. He rides fancy vehicles, from cycle and tractors to a lion with wings, i.e. when he is not himself flying with his hands as wings and legs as parachute. He endorses multiple religious icons – Ram, Allah, Waheguru; and insists on fighting against every social evil – corruption, drug abuse, prostitution, etc. – albeit, as a single-handed miracle worker.

Ram Rahim addresses himself as a fakir, but is seen in elaborate never-repeating costumes that feature some heady imaginations with bling that you would ever see. He rides fancy vehicles, from cycle and tractors to a lion with wings, i.e. when he is not himself flying with his hands as wings and legs as parachute. He endorses multiple religious icons – Ram, Allah, Waheguru; and insists on fighting against every social evil – corruption, drug abuse, prostitution, etc. – albeit, as a single-handed miracle worker. Interestingly, he takes the idea of being comfortable with one’s self, to an altogether different level of dare in our chiselled times, by not batting an eyelid before baring his hairy-bear self or his love handles through outfits un-flattering hugging his corpulence.

Interestingly, he takes the idea of being comfortable with one’s self, to an altogether different level of dare in our chiselled times, by not batting an eyelid before baring his hairy-bear self or his love handles through outfits un-flattering hugging his corpulence. No one discounts that MSG and the subsequent Ram Rahim helmed films had an agenda. None can now deny that a lot was hunky-dory under his publicised ‘reign of bliss’ at the Dera. But anyone with an iota of filmmaking experience can also not deny that to assemble such a humongous cast of real people as happy extras and then getting the best out of them isn’t the outcome of faith and fear alone. What made so many see a spiritual guide in someone with such an unabashed lust for material possessions in a culture that used to associate simplicity and renunciation with saintliness, warrants introspection. If religion, as Marx said could be ‘the opium of the masses’, Ram Rahim for sure served a recipe of relief, even if momentary, for at least some in our compromised times of compromising idols.

No one discounts that MSG and the subsequent Ram Rahim helmed films had an agenda. None can now deny that a lot was hunky-dory under his publicised ‘reign of bliss’ at the Dera. But anyone with an iota of filmmaking experience can also not deny that to assemble such a humongous cast of real people as happy extras and then getting the best out of them isn’t the outcome of faith and fear alone. What made so many see a spiritual guide in someone with such an unabashed lust for material possessions in a culture that used to associate simplicity and renunciation with saintliness, warrants introspection. If religion, as Marx said could be ‘the opium of the masses’, Ram Rahim for sure served a recipe of relief, even if momentary, for at least some in our compromised times of compromising idols. The memory of his crime’s long distance from punishment may have made the Baba of Bling gravitate with a new-found lure towards the tinsel world like a rejuvenating attraction of a parallel career happening mid-life. With an assured fan base of politicians across ideologies, just when Ram Rahim was all set to become Bollywood’s latest B-Movie star in superhero spectacles with a Marvel-comic like proliferation, the Master-Writer up there, introduced a blast from the past twist to script a dramatic anti-climax far memorable than any of His imposter namesake’s films.

The memory of his crime’s long distance from punishment may have made the Baba of Bling gravitate with a new-found lure towards the tinsel world like a rejuvenating attraction of a parallel career happening mid-life. With an assured fan base of politicians across ideologies, just when Ram Rahim was all set to become Bollywood’s latest B-Movie star in superhero spectacles with a Marvel-comic like proliferation, the Master-Writer up there, introduced a blast from the past twist to script a dramatic anti-climax far memorable than any of His imposter namesake’s films. The article was first published as a column piece in Sunday Talkies column of Orissa Post, Sept. 3 2017.

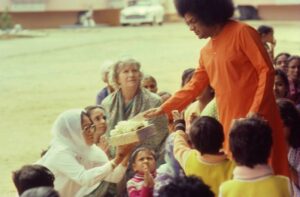

The article was first published as a column piece in Sunday Talkies column of Orissa Post, Sept. 3 2017. Prema Sai (aka Sharavana Baba) with former Sovietologist Ramnath Narayanswamy (the author’s father). Courtesy Dhruv Ramnath.

Prema Sai (aka Sharavana Baba) with former Sovietologist Ramnath Narayanswamy (the author’s father). Courtesy Dhruv Ramnath. Pictures inside Prema Sai’s family’s shrine in Sreekrishnapuram, Kerala, south India, in 2017. Courtesy Dhruv Ramnath.

Pictures inside Prema Sai’s family’s shrine in Sreekrishnapuram, Kerala, south India, in 2017. Courtesy Dhruv Ramnath. Notice the background with Shirdi Sai Baba, Prema Sai Baba and Sathya Sai Baba. Courtesy Dhruv Ramnath.

Notice the background with Shirdi Sai Baba, Prema Sai Baba and Sathya Sai Baba. Courtesy Dhruv Ramnath. From the author’s

From the author’s

I wonder why I do not.

I wonder why I do not.

Picture of Sai Baba courtesy

Picture of Sai Baba courtesy